What is composite volcano?

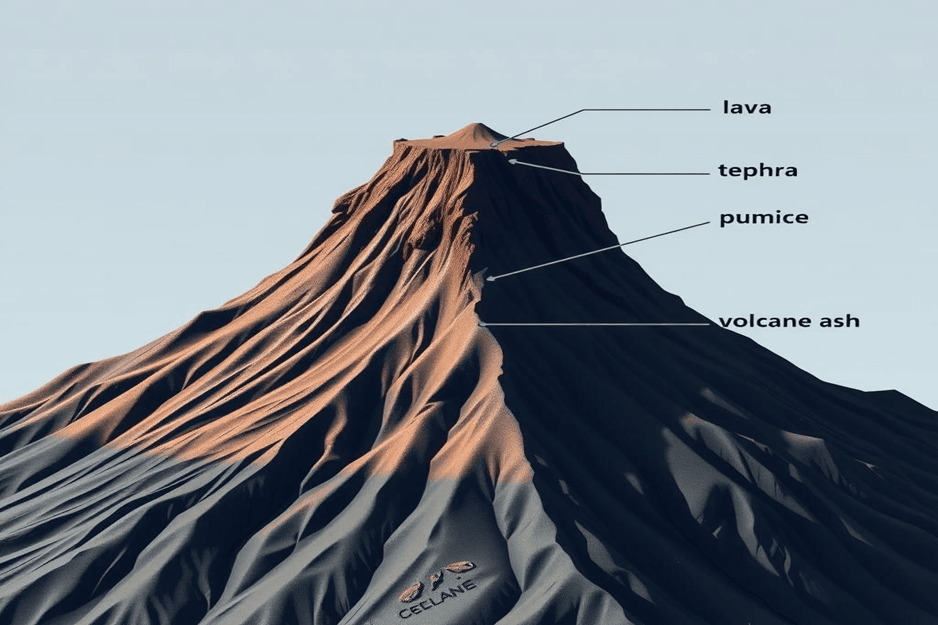

A stratovolcano, alternatively termed a composite volcano, is a predominantly conical volcanic structure formed through successive, alternating deposits of solidified lava and tephra. In contrast to shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes exhibit a steep-sided morphology featuring a summit crater and are associated with explosive eruptive behavior. Certain stratovolcanoes possess summit depressions known as calderas, resulting from structural collapse. The lava extruded from these volcanoes generally solidifies rapidly due to its elevated viscosity, thereby restricting its lateral dispersion. This lava commonly originates from felsic magma, which is enriched in silica—ranging from high to intermediate levels—manifesting as rhyolite, dacite, or andesite, with a comparatively minor presence of low-viscosity mafic magma. While extensive felsic lava flows are atypical, some have traversed distances up to 8 kilometers (5 miles).

The designation “composite volcano” arises from the observation that their layered composition is frequently irregular and heterogeneous rather than uniformly stratified. Stratovolcanoes represent one of the most prevalent volcanic forms; over 700 have discharged lava during the Holocene Epoch (the past 11,700 years), and numerous extinct specimens trace their origins to the Archean Eon. Though predominantly located at subduction zones, stratovolcanoes can also emerge in alternative tectonic contexts. Noteworthy instances of historically catastrophic stratovolcanic activity include Krakatoa in Indonesia (1883), responsible for approximately 36,000 fatalities, and Mount Vesuvius in Italy (79 A.D.), which resulted in an estimated 2,000 deaths. More recent eruptions, such as Mount St. Helens in Washington State (1980) and Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines (1991), also exhibited severe explosive activity, albeit with fewer casualties.

Definitive identification of stratovolcanoes on extraterrestrial bodies within the Solar System remains inconclusive. However, Zephyria Tholus, located in the Aeolis region of Mars, has been postulated as one of two potential stratovolcanic formations.

Distribution of Stratovolcano/composite volcano

Stratovolcanoes are predominantly associated with subduction zones, where they align in chains or clusters along tectonic plate boundaries. These formations occur where an oceanic plate descends beneath a continental plate (continental arc volcanism, as seen in the Cascade Range, Andes, and Campania) or another oceanic plate (island arc volcanism, exemplified by Japan, the Philippines, and the Aleutian Islands).

In addition, stratovolcanoes arise in other tectonic environments, including intraplate volcanism on remote oceanic islands that are not located near plate margins. Illustrative examples include Teide in the Canary Islands and Pico do Fogo in Cape Verde. Furthermore, stratovolcanoes have developed within continental rift zones, as demonstrated by Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania and Longonot in Kenya, both situated in the East African Rift.

Formation of Stratovolcano/composite volcano

Volcanoes within subduction zones originate when hydrous minerals embedded in the descending oceanic plate are conveyed into the mantle. These minerals—such as chlorite and serpentine—release water as they are subjected to increasing pressure and temperature, which significantly lowers the mantle’s melting point by approximately 60 to 100 °C. This process, termed dewatering, induces partial melting of the mantle—a phenomenon known as flux melting—that subsequently generates magma. As the magma ascends through the overlying crust, it interacts with and assimilates silica-rich rocks, culminating in a magma of intermediate composition. Upon nearing the Earth’s surface, this magma accumulates in a subterranean magma chamber beneath the stratovolcano.

The precise mechanisms that initiate eruptive activity remain an active area of investigation. Several proposed processes include:

- Magma differentiation, wherein lighter, more silica-enriched magma along with volatile components—such as water, halogens, and sulfur dioxide—accumulates at the chamber’s apex, potentially generating substantial internal pressures.

- Fractional crystallization, during which anhydrous minerals like feldspar crystallize and separate from the magma. This increases the concentration of volatiles in the residual melt, possibly triggering a second boiling, which facilitates gas-phase separation (e.g., carbon dioxide or water vapor) and elevates chamber pressure.

- Magma injection, involving the intrusion of fresh, hotter magma into the chamber, which mixes with and heats the pre-existing cooler magma. This thermal and chemical interaction may expel volatiles from solution and reduce the density of the resident magma, both of which serve to intensify pressure. Substantial evidence for such magma mixing prior to eruption includes the presence of magnesium-rich olivine crystals in newly erupted silicic lavas that lack a reaction rim—an occurrence only feasible if the eruption ensued shortly after mixing, as olivine rapidly reacts with silicic magma to form pyroxene rims.

- Progressive thermal melting of the encasing country rock.

These internal triggers can be influenced or amplified by external events, such as sector collapse, seismic activity, or interactions with groundwater. However, the effectiveness of each trigger is often constrained by specific conditions. For instance, sector collapse—entailing the massive landslide of a volcano’s flank—can instigate eruption only if the magma chamber lies at shallow depth. Conversely, magma differentiation and thermal expansion are generally ineffective as eruption triggers for magma chambers situated at significant depths.

Hazards

Throughout documented history, explosive volcanic events associated with subduction zones—convergent tectonic boundaries—have represented the primary geological threat to human societies. Stratovolcanoes situated in such zones, including Mount St. Helens, Mount Etna, and Mount Pinatubo, typically undergo violent eruptions. This behavior is attributed to the magma’s high viscosity, which inhibits the unobstructed release of volcanic gases. As a result, immense internal pressures accumulate due to gas entrapment within the viscous magma. Once the volcanic conduit is ruptured and the crater is exposed, these gases are rapidly released in a highly explosive manner, propelling both magma and gas with exceptional velocity and intensity.

Since the year 1600 CE, volcanic eruptions have resulted in the deaths of nearly 300,000 individuals. The majority of these fatalities have been caused by pyroclastic flows and lahars, which are among the most dangerous and destructive phenomena linked to explosive eruptions of subduction-related stratovolcanoes. Pyroclastic flows are swift, incandescent, ground-hugging avalanches composed of hot volcanic fragments, pulverized ash, disintegrated lava, and superheated gases, capable of traveling at velocities exceeding 150 kilometers per hour (90 miles per hour). For example, during the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée on Martinique in the Caribbean, approximately 30,000 people were killed by such flows. Similarly, in March and April of 1982, El Chichón in Chiapas, southeastern Mexico, erupted three times, resulting in the most catastrophic volcanic event in that nation’s history and claiming the lives of over 2,000 people due to pyroclastic activity.

Two notable eruptions in 1991 of volcanoes classified as Decade Volcanoes further illustrate the hazards associated with stratovolcanoes. On June 15th, Mount Pinatubo erupted explosively, propelling an ash column 40 kilometers (25 miles) into the atmosphere. This eruption triggered extensive pyroclastic surges and destructive lahar floods, inflicting widespread damage in the vicinity. Situated in Central Luzon approximately 90 kilometers (56 miles) west-northwest of Manila, Mount Pinatubo had remained dormant for over 600 years prior to the event. The 1991 eruption ranks as the second most powerful of the 20th century and generated a vast volcanic ash plume that measurably impacted global temperatures, with reductions of up to 0.5 °C in certain regions. The ash plume carried 22 million tons of sulfur dioxide (SO₂), which combined with atmospheric water to form sulfuric acid aerosols. In the same year, Japan’s Mount Unzen, located on Kyushu Island roughly 40 kilometers (25 miles) east of Nagasaki, also erupted following two centuries of quiescence. Beginning in June, the formation and subsequent collapse of a lava dome initiated rapid pyroclastic flows descending the slopes at speeds reaching 200 kilometers per hour (120 miles per hour). This eruption marked one of the worst volcanic catastrophes in Japan’s recorded history, echoing a prior disaster in 1792 that claimed more than 15,000 lives.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD remains the most widely recognized instance of a hazardous stratovolcanic event. This eruption buried the ancient Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum under massive pyroclastic surges and pumice layers ranging from 6 to 7 meters in depth. At the time, Pompeii had a population estimated between 10,000 and 20,000. Mount Vesuvius is currently regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes on Earth, owing to its potential for highly explosive eruptions and its proximity to the densely populated Metropolitan Naples region, which encompasses approximately 3.6 million residents.

Ash

Beyond their potential to influence global climatic patterns, volcanic ash clouds generated by explosive eruptions represent a significant threat to aviation safety. These ash clouds are composed of minute rock fragments, mineral particles, and volcanic glass, typically ranging in size from silt to sand. The individual ash grains possess sharp, abrasive edges and are non-soluble in water. A case in point occurred during the 1982 eruption of Galunggung in Java, when British Airways Flight 9 inadvertently entered an ash plume, resulting in temporary engine malfunction and structural impairment. Although no fatal accidents have yet occurred directly due to ash encounters, over 60 aircraft—predominantly commercial—have sustained damage, with several necessitating emergency landings. Volcanic ash deposition also presents serious health hazards through inhalation and constitutes a threat to property. A single square yard covered with a 4-inch layer of ash may weigh between 120 and 200 pounds, a figure that can double when the ash becomes saturated. Moreover, wet ash endangers electronic systems due to its conductive properties. In some cases, dense and intensely hot ash clouds are discharged during the collapse of eruptive columns or through lateral explosions stemming from the partial failure of volcanic domes or edifices during explosive events. These ash-laden flows, termed pyroclastic surges, comprise superheated lava fragments, pumice, rocks, and volcanic gases in addition to ash. Traveling at velocities exceeding 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph) and with temperatures ranging from 200 °C to 700 °C, these surges are capable of inflicting extensive damage to both infrastructure and human life along their path.

Lava

Lava emissions from stratovolcanoes generally pose minimal direct danger to human or animal life, as the highly viscous nature of the lava ensures it advances at a sufficiently slow pace to allow for evacuation. Fatalities linked to lava flows are usually due to indirect causes such as gas inhalation or eruptive explosions. However, lava can engulf residential and agricultural zones, entombing structures in solidified rock and significantly diminishing land value. Not all stratovolcanoes emit viscous lava; for instance, Nyiragongo, situated near Lake Kivu in central Africa, is exceptionally hazardous due to its magma’s unusually low silica content, which results in low viscosity and allows the lava to flow rapidly. Such fluid lava may produce towering fountains, whereas more viscous lava can solidify within the vent, forming a volcanic plug. These plugs trap gases and may cause pressure to accumulate in the magma chamber, potentially triggering violent eruptions. The temperature of lava generally falls within the range of 700 to 1,200 °C (1,300–2,200 °F).

Volcanic bombs

Volcanic bombs are semi-molten masses of rock and lava expelled forcefully during volcanic activity. By definition, these projectiles exceed 64 mm (2.5 inches) in diameter, while fragments between 2 and 64 mm are categorized as lapilli. Upon ejection, bombs remain in a partially molten state and continue to cool and solidify during their descent. They often assume ribbon-like, oval, or flattened forms upon impact with the ground. These materials are typically associated with Strombolian and Vulcanian eruptions involving basaltic magma. Documented ejection velocities for volcanic bombs range from 200 to 400 meters per second, making them capable of causing considerable physical destruction.

Lahar

Derived from the Javanese term for volcanic mudflows, lahars are turbulent mixtures of water and fragmented volcanic material. These flows may be triggered by heavy rainfall occurring before or during an eruption or through the melting of snow and ice due to volcanic activity. When meltwater interacts with unconsolidated volcanic debris, it forms a fast-moving slurry. Lahars typically consist of approximately 60% sediment and 40% water; depending on the concentration of debris, the flow may vary from highly fluid to a concrete-like consistency. Their immense momentum and density enable them to obliterate structures and cause severe injuries, reaching speeds of several dozen kilometers per hour. A tragic illustration is the 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia, where pyroclastic activity melted the snow and ice covering the 5,321-meter (17,457-foot) Andean peak. The resulting lahar inundated the city of Armero and neighboring communities, claiming 25,000 lives in one of the most devastating volcanic disasters in modern history.

Volcanic gas

During the development of a volcano, a variety of gases become integrated with magma within the subterranean volcanic reservoir. These gases are subsequently emitted into the atmosphere during eruptive events, posing a serious risk of toxic exposure to humans. The primary gaseous component is water vapor (H₂O), followed in abundance by carbon dioxide (CO₂), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), and hydrogen fluoride (HF). When present in atmospheric concentrations exceeding 3%, inhalation of CO₂ can result in dizziness and respiratory distress. Exposure to concentrations surpassing 15% proves fatal. Because CO₂ is heavier than air, it tends to accumulate in low-lying terrain, forming lethal, odorless gas pockets. SO₂ is classified as an irritant to the respiratory tract, skin, and ocular tissues upon contact. It is distinguished by a pungent, sulfurous odor and is notable for its destructive impact on the ozone layer, as well as its ability to generate acid rain in areas downwind from an eruption. H₂S, which possesses an even more intense odor than SO₂, is also significantly more toxic. Inhalation of concentrations above 500 parts per million for less than an hour can lead to death. HF and chemically related compounds are capable of adhering to ash particles, and upon deposition, may contaminate both soil and water sources. In addition to eruptive emissions, volcanic systems also undergo degassing—a passive outgassing process that occurs even during dormant intervals—contributing continuously to the release of hazardous gases.

People also ask

What is the difference between a volcano and a stratovolcano?

A volcano is a general term referring to any geological structure that allows magma, volcanic gases, and ash to escape from beneath the Earth’s crust. In contrast, a stratovolcano—also known as a composite volcano—is a specific type of volcano characterized by a steep, conical shape formed through alternating layers of lava, volcanic ash, and pyroclastic debris. Stratovolcanoes, such as Mount St. Helens and Mount Pinatubo, are notable for their explosive eruptions due to the high viscosity of their magma and the crucial buildup of internal gas pressure.

Is Yellowstone a stratovolcano or shield volcano?

Yellowstone is not classified as a stratovolcano; it is a supervolcano, more closely related in structure to a caldera-forming system than a typical stratovolcano or shield volcano. Yellowstone’s eruptive history and structure distinguish it from stratovolcanoes such as Mount Unzen or Mount Pinatubo.

What is the definition of a stratovolcano?

A stratovolcano is a type of volcano constructed from multiple eruptions over time, forming layers of hardened lava, ash, and volcanic rock. These volcanoes are typically found at subduction zones and are fundamental contributors to some of the most violent eruptions in recorded history due to the high gas content and viscosity of their magma.

What is a famous example of a stratovolcano?

Mount Vesuvius is one of the most famous stratovolcanoes, recognized for its notable eruption in 79 AD, which devastated the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum through pyroclastic surges and extensive ash deposits.

What is the most active stratovolcano in the world?

The most active stratovolcano globally, Mount Unzen and Mount Pinatubo are cited as significant examples of highly active stratovolcanoes, both having erupted in 1991 after long periods of dormancy. However, Kīlauea (a shield volcano) and Indonesia’s Mount Merapi are widely recognized in global literature for frequent activity.

Is Mount St. Helens a stratovolcano?

Yes, Mount St. Helens is a stratovolcano, located in the United States. It is noteworthy for its 1980 eruption, which is among the most significant volcanic events in U.S. history and aligns with the typical explosive behavior of subduction-zone stratovolcanoes

What is the deadliest part of a stratovolcano?

The most deadly hazards associated with stratovolcanoes are pyroclastic flows and lahars. Pyroclastic flows, which consist of high-speed, ground-hugging clouds of ash, gas, and debris, have caused widespread fatalities, as seen during the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée. Lahars, or volcanic mudflows, are equally crucial threats due to their destructive force and rapid movement.

Is Mount Fuji a stratovolcano?

Yes, Mount Fuji is classified as a stratovolcano.

What is the largest volcano in the world?

Mauna Loa in Hawaii holds the title of the largest volcano by volume and area. It is a shield volcano, differing significantly in structure and eruptive style from stratovolcanoes like Mount Pinatubo or Mount St. Helens.

What is the difference between a volcano and a stratovolcano?

A volcano is a general geological structure through which magma, gas, and ash escape to the Earth’s surface. A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a specific type characterized by steep profiles and formed through alternating layers of lava, volcanic ash, and pyroclastic material. Stratovolcanoes often exhibit explosive eruptions due to their viscous magma and trapped volcanic gases, making them more hazardous compared to other volcano types.

Why is a composite or stratovolcano so dangerous?

A composite volcano, also known as a stratovolcano, is considered especially dangerous due to its potential for explosive eruptions, caused by the accumulation of viscous magma and trapped volcanic gases. These eruptions can generate pyroclastic surges, volcanic bombs, and ash clouds, all of which pose severe threats to human life, aviation, infrastructure, and the environment. The combination of high temperatures, rapid flow velocities, and toxic gases contributes to the stratovolcano’s deadly potential.

What is the main danger of a stratovolcano?

The primary hazard associated with a stratovolcano is the occurrence of pyroclastic surges—high-density flows of superheated volcanic ash, lava fragments, and gas that travel at speeds exceeding 50 mph with temperatures between 200°C and 700°C. Additionally, lahars, or volcanic mudflows, represent another critical danger, capable of destroying entire settlements, as demonstrated by the 1985 Nevado del Ruiz eruption, which caused 25,000 fatalities.

What happens when a stratovolcano erupts?

When a stratovolcano erupts, it typically expels a combination of volcanic ash, lava, gases, and pyroclastic materials. These eruptions can be violent, releasing volcanic bombs, triggering lahars, and creating ash clouds hazardous to aviation and public health. Volcanic degassing may also occur, releasing toxic gases even during dormant periods. Eruptions may cause engine failure, property destruction, and environmental contamination, depending on their magnitude and characteristics.

Why are stratovolcanoes so explosive?

Stratovolcanoes exhibit explosive behavior due to the presence of high-viscosity magma that traps volatile gases such as sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon dioxide within the volcanic chamber. This pressure buildup eventually overcomes the structural resistance, leading to violent eruptions. In some cases, lava solidifies within the vent, forming a volcanic plug that further intensifies pressure, increasing the likelihood of a catastrophic explosion.

Largest stratovolcano

Stratovolcanoes such as Mount Fuji and Mount Pinatubo are among the most notable for their scale and impact. These volcanoes are characterized by towering structures and layered compositions of lava and ash, making them significant geological formations.