Abraham Ortelius, a Dutch cartographer, is credited as the earliest individual to propose that North and South America, along with Europe and Africa, were once united as a single landmass, dating back to the year 1596. Later in 1858, Antonio Snider produced a map portraying the three continents in a connected formation; however, this depiction starkly contradicted the dominant scientific paradigms of that period and was, therefore, largely disregarded. In 1910, F.B. Taylor from the United States advanced the concept of lateral displacement of the continents—termed continental drift—in an attempt to interpret the spatial distribution of major mountain systems.

Continental Drift Theory of Alfred Wegener

The theory was extensively articulated by Alfred Wegener, a German meteorologist, in 1912, under the title “Continental Drift Theory.” Wegener, being a climatologist, endeavored to account for the variations in climatic patterns observed throughout Earth’s geological history. A wealth of geological evidence supports the claim that there were substantial and widespread climatic transformations in the past. Wegener deduced that either the climatic zones had shifted position or, alternatively, the continental landmasses themselves had migrated. Given that the distribution of the Earth’s climatic belts is primarily governed by solar radiation, it appeared more plausible to him that the continents had undergone spatial repositioning.

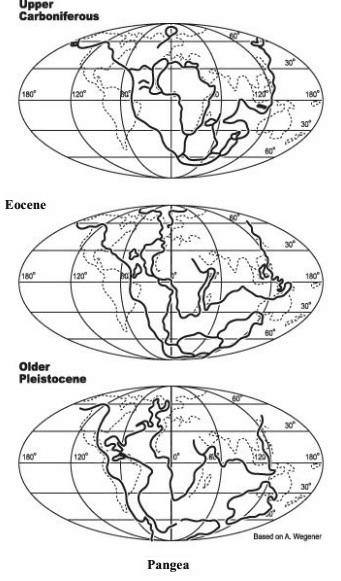

Wegener proposed that all present-day continents were once part of a singular landmass, encircled by a vast oceanic expanse. He referred to this supercontinent as PANGAEA, a term derived from Greek signifying “all Earth,” while the enveloping ocean was designated as PANTHALASSA, meaning “all water” (refer to figure 1a). According to his model, during the Carboniferous period, the South Pole was located proximate to the present South African coast, whereas the North Pole lay within the Pacific Ocean.

Wegener maintained that approximately 200 million years ago, the supercontinent Pangaea commenced fragmentation. This initial division resulted in two primary landmasses—Gondwanaland and Laurasia—which began to diverge, with marine transgressions from Panthalassa forming a shallow sea, subsequently named the Tethys Sea. The contemporary configurations and relative spatial arrangements of the continents emerged from the breakup of Pangaea through a process of rifting and continental dispersal (see figure 2). Wegener characterized this separation movement as Polflucht, a term meaning “flight from the poles.” He incorporated the Isostasy theory, positing that the continental masses—composed of SIAL (silica and aluminium)—float atop the denser oceanic crust, which consists of SIMA (silica and magnesium).

Evidences in Support of the Theory

A multitude of evidentiary elements have been advanced to substantiate the continental drift theory. These are delineated as follows:

(a) Continental Correspondence (“Jigsaw Fit”) – The coastlines of Africa and South America, which face each other, exhibit an extraordinary alignment, strongly suggesting prior connectivity. Notably, a map devised using computer modeling techniques by Bullard in 1964 to optimize the fit of the Atlantic boundaries demonstrated a nearly perfect match. This alignment was computed not at the contemporary shoreline but along the 1,000-fathom depth contour.

(b) Identical-Aged Rock Formations Across Ocean Basins – A band of Precambrian rocks, estimated at 2,000 million years old, found along Brazil’s coast, shows a precise correlation with formations located in western Africa. Additionally, the earliest marine strata on the coastal fringes of South America and Africa date back to the Jurassic period, implying that the Atlantic Ocean did not predate that era. Furthermore, the Appalachian mountain range in North America, which terminates at the eastern seaboard, maintains its geological trend across the North Atlantic into the ancient Hercynian mountains of southwestern Ireland, Wales, and central Europe.

(c) Tillite Deposits – This refers to a sedimentary rock generated from glacial deposits. The Gondwana stratigraphic sequence in India contains a prominent tillite layer at its base, indicative of extensive glaciation. Equivalent geological successions are found in Africa, the Falkland Islands, Madagascar, Antarctica, and Australia, in addition to India, which strongly confirms a shared paleoclimatic history among these southern hemisphere landmasses.

(d) Placer Mineral Accumulations – The occurrence of rich gold placer deposits along the Ghanaian coast, in the absence of local source rocks, is a compelling observation. The primary auriferous veins are situated in Brazil, implying that these placer deposits were likely derived from the Brazilian plateau during the era when both landmasses were geographically contiguous.

(e) Fossil Distribution Patterns – The discovery of Lemur fossils in India, Madagascar, and Africa gave rise to the hypothesis of a now-submerged land bridge, termed “Lemuria,” that once united these regions. Additionally, the Mesosaurus, a small aquatic reptile adapted to shallow brackish habitats, is known only from fossil records in two geographically isolated areas: southern Cape Province (South Africa) and the Iraver formations of Brazil. Despite being separated by a 4,800 km wide ocean, the identical fossil evidence signifies a time when both regions formed a continuous landmass, enabling species to inhabit a shared ecosystem.

Forces for Drifting

Alfred Wegener postulated that the mechanism underlying the continental displacement was driven by two principal forces: the pole-fleeing force and the tidal force. The pole-fleeing force is associated with the Earth’s rotation, which, as per Wegener’s interpretation, exerted a centrifugal influence that propelled the continental masses toward the equatorial region. On the other hand, the tidal force, arising from the gravitational attraction exerted by the Moon and the Sun, was identified by Wegener as the dominant cause of the westward migration of the American continents. He asserted that while these forces may appear weak in the short term, they could become significantly effective when operating over geological timescales spanning millions of years.

Criticism of Wegener’s Theory

While it is evident that Wegener assembled a substantial body of evidence in defense of his hypothesis—much of which was persuasive—numerous aspects of his theory were rooted in speculative reasoning and insufficient empirical substantiation, prompting intense academic scrutiny and widespread debate.

(a) The most prominent criticism pertained to the mechanical forces suggested to explain the continental drift. It has been calculated that the tidal forces would need to be ten billion times greater than their current magnitude to produce the continental-scale movements described.

(b) Wegener’s assertion that the Rocky Mountains and the Andes were formed during the westward displacement of the Americas was also challenged. If the continental crust (SIAL) is buoyantly resting atop the denser oceanic substratum (SIMA), then the latter would be incapable of generating the compressional resistance required to deform and uplift the crust into major mountain chains.

(c) The “jigsaw fit” observed between the opposing Atlantic coasts was also criticized as imperfect, with irregularities and mismatches undermining the assertion of a precise former alignment.

(d) Although similarities in geological structure and stratigraphy were identified on either side of the Atlantic, critics contended that these parallels were not conclusive evidence that the continental margins were once physically connected, nor did they definitively support the claim of continental continuity.

What does continental drift explain?

Continental drift explains the gradual movement of Earth’s continental landmasses over geological time. It provides a theoretical framework for understanding the present-day configuration of continents and the historical processes that led to their separation from a single supercontinent into their current geographical positions.

Who first discovered continental drift?

The initial concept of connected continents was proposed by Abraham Ortelius in 1596. However, the comprehensive theory of continental drift was formulated by Alfred Wegener in 1912, who supported it with geological, fossil, and climatic evidence.

Is continental drift theory true?

While the original theory by Wegener had limitations, many of its core ideas have been validated through modern plate tectonics. The notion that continents move over time is now widely accepted, although the mechanisms proposed by Wegener were later revised and refined.

Who proved continental drift?

Alfred Wegener is credited with systematically arguing for continental drift, but it was later substantiated by the theory of plate tectonics in the mid-20th century through technological advancements such as seafloor mapping and paleomagnetism.

What is the evidence of Pangea?

Evidence includes the fit of continental margins, continuity of mountain ranges, similar rock sequences, and fossil correlations across continents. These collectively suggest that all landmasses were once united in a supercontinent, Pangaea, around 200 million years ago.

What is the name of the supercontinent?

The supercontinent was called PANGAEA, a Greek-derived term meaning “all Earth.” It was surrounded by a vast ocean named PANTHALASSA, meaning “all water.”

What are the two types of plates found on the crust?

Earth’s crust consists of two primary types of lithospheric plates:

Continental plates (composed mainly of SIAL—silica and aluminium),

Oceanic plates (composed primarily of SIMA—silica and magnesium).