Controls of Climate

Climatic controls are the factors affecting the climate of a particular place. The most fundamental control of both weather and climate is the unequal heating and cooling of the atmosphere in different parts of the earth. While the earth as a whole loses as much heat to space as it gains from the sun, some parts experience a net gain and others a net loss. The unequal heating occurs on a wide variety of geographic scales, the largest and most important of which is the differential between high and low latitudes. But heating and cooling differences also exist between continents and oceans, between snow-covered and snow-free areas, between forested and cultivated land, and even between cities and their surrounding countrysides. These heating and cooling differences, and the air movements (winds) they induce, represent the overall general background control of weather and climate. The more specific controls are derived from various geographic factors.

A) Latitudinal Variations in Solar Radiation

Latitudinal differences in the amounts of solar energy received are the most basic climatic control. In low latitudes, the sun is high in the sky, the solar radiation is intense, and the climate is warm and tropical; in high latitudes, the sun is lower in the sky, the solar radiation is weaker, and the climate is colder. The zone of maximum solar radiation shifts northward and southward during the year, thereby producing the seasons. The effectiveness of solar heating also varies with the nature of the surface on which the sunshine falls. Thus, a strongly reflecting snow surface is heated much less than a land surface lacking snow.

B) Altitudes

Since within the troposphere temperature normally decreases with increasing altitude, places at higher elevations are likely to have lower temperatures (and often also more precipitation) than adjacent lowlands. Thus, altitude is a climatic control. Where a high mountain chain lies athwart the path of prevailing winds, it acts to block the movement of air and hence the transfer of warm or cold air masses. In addition, the upward thrust of air on a mountain’s windward side and the downward movement of air on its lee side tend to make for increased precipitation in the former instance and a decrease in the latter.

C) Distribution of Continents and Oceans

Continents heat and cool more rapidly than do oceans. Consequently, non-coastal continental areas experience more intense summer heat and winter cold than do oceanic and coastal areas.

D) Pressure and Wind Systems

Differences in heating and cooling between high and low latitudes, between land and water areas, and between snow-covered and bare land surfaces lead not only to regional temperature contrasts but also to differences in atmospheric pressure, which in turn induce air movements (winds). Air in motion, which in itself is an important element of weather and climate, also operates as a control, for it serves as a transporter of heat from regions of net heat gain to regions of net loss. And just as there is a great variety of geographic scales of differential heating and cooling of terrestrial surfaces, so there is a great variety of scales relating to atmospheric pressure and atmospheric motion. They range from those of hemispheric magnitude, such as the belts of westerly winds in middle latitudes and the belts of easterlies that encircle the low latitudes, to the small but extremely violent tornado.

The mobile low-and high-pressure systems which bring day-to-day weather changes and are conspicuous features on daily weather maps are of a common scale of atmospheric motion. The frequency of occurrence and the paths followed by these transient mobile pressure and wind systems are important factors in determining climate. Some pressure and wind systems, especially the highs over the subtropical oceans, tend to be semi-permanent in position, and they too are of great climatic importance.

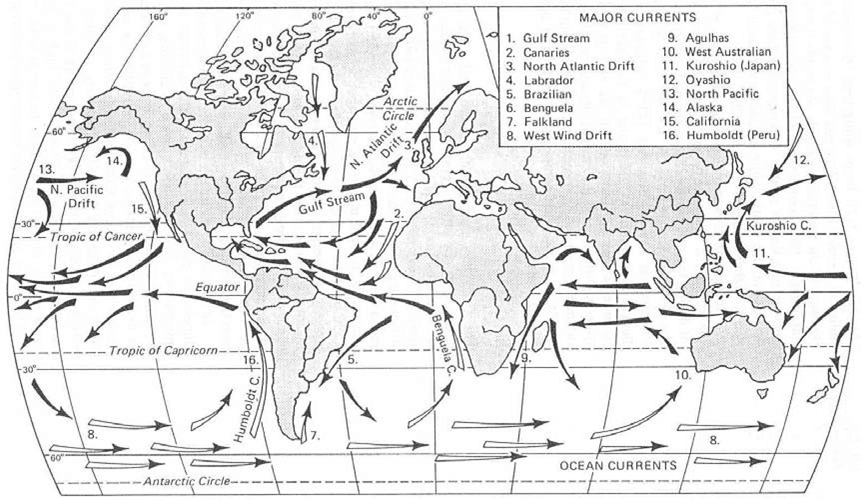

E) Ocean Currents

Ocean currents, both warm and cold, which are largely induced by the major wind systems, are also an important climatic control. They are highly important in transporting warmth and chill in a north-south direction, and in so doing give some coastal regions distinctive climates.

F) Local Features

Finally, the climate of a place is affected by a variety of local features, such as its exposure, the slope of the land, and the characteristics of vegetation and soil. In the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing slopes receive more direct sunlight and have a warmer climate than those with a northern exposure, which not only face away from the sun but are also more open to cold northerly winds. Areas with sandy, loosely packed soil, because of their low heat conductivity, are inclined to experience more frosts than do areas with hard-packed soils; valleys normally have more frequent and severe frosts than the adjacent slopes; and cities are usually warmer than the adjacent countrysides.