How do we know the temperature of an ancient ocean from 100 million years ago, or the heat of a magma chamber long turned to stone? The answer lies in the atomic weight of oxygen. Isotope Thermometry acts as Earth’s “paleo-thermometer,” utilizing the temperature-dependent exchange of Oxygen-16 and Oxygen-18 between minerals. Whether you are studying sedimentary paleoclimates or high-grade metamorphic terrains, understanding isotopic fractionation is essential for modern geochemistry. This guide covers the fundamental principles, calibration techniques, and essential coefficients needed to calculate geological temperatures.

Principles of Oxygen Isotope Geothermometry

One of the first applications of the study of oxygen isotopes to geological problems was geothermometry. Urey (1947) suggested that the enrichment of 18O in calcium carbonate relative to seawater was temperature-dependent and could be used to determine the temperature of ancient ocean waters. The idea was quickly adopted, and paleotemperatures were calculated for the Upper Cretaceous seas of the northern hemisphere. Subsequently, a methodology was developed for application to higher-temperature systems based upon the distribution of 18O between mineral pairs. An excellent review of the methods and applications of oxygen isotope thermometry is given by Clayton (1981).

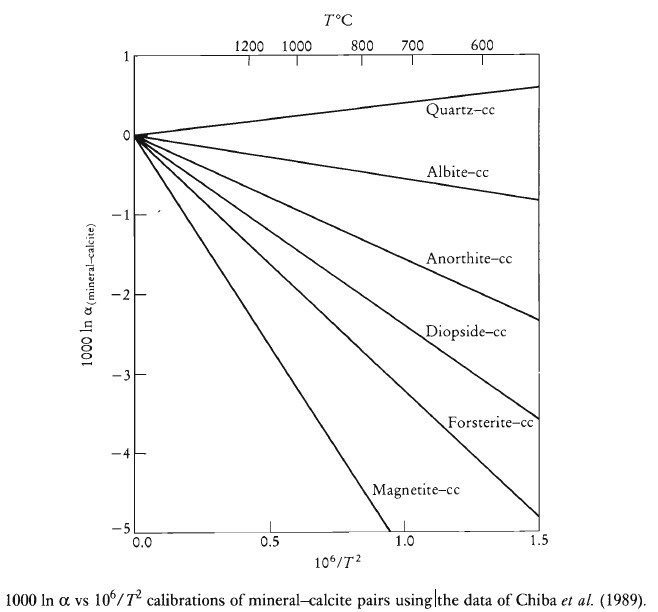

The expression summarizing the temperature dependence of oxygen isotopic exchange between a mineral-pair is often simplified where the fractionation factor is simply a function of 1/T. Empirical observations indicate that a graph of ln α vs 1/T2 is linear over a temperature range of several hundred degrees, and a plot of this type for a pair of anhydrous phases should also pass through the origin. Isotopic fractionations decrease with increasing temperature, so oxygen isotope thermometers might be expected to be less sensitive at high temperatures. However, experimental studies are most precise at high temperatures, and reliable thermometers have been calibrated for use with igneous and metamorphic rocks.

Oxygen isotope thermometry has a number of advantages over conventional cation-exchange thermometry; for example, oxygen isotopic exchange can be measured between many mineral pairs in a single rock. In addition, minerals with low oxygen diffusivities such as garnet and pyroxene are capable of recording peak temperature conditions.

Calibration Methods: Theoretical vs. Experimental Approaches

There are a large number of different calibrations of oxygen isotope exchange reactions, some of which give conflicting results. This has given rise to much confusion over which calibrations can be used as a basis for reliable thermometry. In brief, there are three different approaches to the calibration of oxygen isotope exchange thermometers—the theoretical approach, experimental methods, and empirical methods.

Theoretical calculations of oxygen isotope fractionations are based upon studies of lattice dynamics. Recent results of this type have been found to agree with new experimental studies by Clayton et al. (1989) and have been used to extrapolate experimental results outside their temperature range (Clayton and Kieffer, 1991).

Experimental studies based upon mineral-water isotopic exchange have been used to calibrate oxygen isotope thermometers, although the more reliable exchange reaction with calcite is now preferred. Calcite-mineral oxygen isotope exchange is stable to relatively high temperatures, and the results can be extrapolated outside the experimental range. Mineral-calcite pairs are combined to give mineral-mineral oxygen isotope fractionation equations. The best thermometers are between mineral-calcite pairs which show the greatest divergence on a ln α vs 1/T diagram. Thus, the mineral-pair quartz-diopside is a sensitive thermometer, for there is significant fractionation of oxygen isotopes between the two minerals, whereas a pair such as quartz-albite is not sufficiently sensitive. Quartz-magnetite fractionation is not widely used because the high diffusivity of oxygen in magnetite means that it cannot record peak temperatures.

Empirical calibrations of oxygen-isotope thermometers are based upon experimental data, which is then applied to a natural assemblage. Given that all the minerals in a rock are in isotopic equilibrium, thermometers can then be calibrated for mineral pairs which have not been experimentally studied. However, the underlying assumption of isotopic equilibrium is rarely fulfilled, making the application of this method questionable.

Currently, the most reliable calibration of oxygen isotope thermometers is based upon a combination of experimental and theoretical studies. Clayton (1991) combined calcite-mineral experimental data with theoretical studies and calculated polynomial expressions for a number of common rock-forming minerals. These expressions may be combined to give mineral-pair thermometers.

Oxygen Isotope Fractionation Factors (Mineral Pairs)

(a) Experimentally determined — Equilibration with Calcite (Chiba et al., 1989)

| Mineral Pair | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Cc – Q | 0.38 |

| Ab – Q | 0.94 |

| An – Q | 1.99 |

| Di – Q | 2.75 |

| Fo – Q | 4.35 |

| Mt – Q | 6.29 |

| Ab – Cc | 0.56 |

| An – Cc | 1.61 |

| Di – Cc | 2.37 |

| Fo – Cc | 3.29 |

| Mt – Cc | 5.91 |

| An – Ab | 1.05 |

| Di – Ab | 0.76 |

| Fo – Ab | 1.68 |

| Mt – Ab | 4.30 |

| Di – An | 0.92 |

| Fo – An | 2.54 |

| Mt – An | 4.85 |

| Fo – Di | 3.54 |

| Mt – Di | 5.27 |

| Mt – Fo | 2.62 |

(b) Experimentally determined — Equilibration with Water (Matthews et al., 1983)

| Mineral Pair | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Q – Ab | 0.50 |

| Jd – Ab | 1.09 |

| An – Ab | 1.59 |

| Di – Ab | 2.08 |

| Wo – Ab | 2.20 |

| Mt – Ab | 6.11 |

| Q – Jd | 0.57 |

| An – Jd | 0.50 |

| Di – Jd | 0.92 |

| Wo – Jd | 1.08 |

| Mt – Jd | 4.52 |

| An – Di | 0.61 |

| Wo – An | 1.14 |

| Mt – An | 4.52 |

| Wo – Di | 0.43 |

| Mt – Di | 3.91 |

| Mt – Wo | 4.30 |

(c) Empirically determined (Bottinga and Javoy, 1975; Javoy, 1977)

| Mineral Pair | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Q – Ab | 0.97 |

| Pl – Ab | 1.59 |

| Px – Ab | 2.75 |

| Q – Pl | 1.08 |

| Px – Pl | 1.24 |

| Px – Mt | 2.91 |

| Gt – Mt | 2.88 |

| Il – Mt | 5.57 |

| Il – Px | 3.59 |

| Gt – Px | 3.29 |

| Il – Gt | 3.70 |

(d) Polynomial Functions for Individual Minerals Used for Calculating Oxygen Isotopic Fractionation Between Mineral-Pairs (Clayton, 1991)

| Mineral Pair | Function |

|---|---|

| Calcite | fCc=11.78x−0.420×2+0.018x3f_{Cc} = 11.78x – 0.420x^2 + 0.018x^3fCc=11.78x−0.420×2+0.018×3 |

| Quartz | fQ=12.116x−0.370x+0.012x2f_{Q} = 12.116x – 0.370x + 0.012x^2fQ=12.116x−0.370x+0.012×2 |

| Albite | fAb=11.34x−0.372×2+0.016x3f_{Ab} = 11.34x – 0.372x^2 + 0.016x^3fAb=11.34x−0.372×2+0.016×3 |

| Anorthite | fAn=9.92x−0.320×2+0.015x3f_{An} = 9.92x – 0.320x^2 + 0.015x^3fAn=9.92x−0.320×2+0.015×3 |

| Diopside | fDi=9.82x−0.299×2+0.022x3f_{Di} = 9.82x – 0.299x^2 + 0.022x^3fDi=9.82x−0.299×2+0.022×3 |

| Forsterite | fFo=8.53x−0.212×2+0.006x3f_{Fo} = 8.53x – 0.212x^2 + 0.006x^3fFo=8.53x−0.212×2+0.006×3 |

| Magnetite | fMt=5.674x−0.383×2+0.003x3f_{Mt} = 5.674x – 0.383x^2 + 0.003x^3fMt=5.674x−0.383×2+0.003×3 |

Geological Applications of Isotope Thermometry

Low-Temperature Thermometry

The earliest application of oxygen isotopes to geological thermometry was in the determination of ocean paleotemperatures. The method assumes isotopic equilibrium between the carbonate shells of marine organisms and ocean water and uses the equation of Epstein et al. (1953), which is still applicable despite some proposed revisions (Friedman and O’Neil, 1977):

TOC = 16.5 – 4.3(OC – Ow) + 0.14(OC – Ow)2

where OC and Ow are respectively the δ18O of CO2 obtained from CaCO3 by reaction with H3PO4 at 25°C and the δ18O of CO2 in equilibrium with the seawater at 25°C.

The method assumes that the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater was the same in the past as today, an assumption which has frequently been challenged and which does not hold for at least parts of the Pleistocene when glaciation removed 18O-depleted water from the oceans. This has the effect of amplifying the temperature variations. The method also assumes that the isotopic composition of oxygen in the carbonate is primary and that the carbonate precipitation was an equilibrium process. Both these assumptions should also be carefully examined. Because the temperatures of ocean bottom water vary as a function of depth, it is also possible to use oxygen isotope thermometry to estimate the depth at which certain benthic marine fauna lived—paleobathymetry.

Low-temperature isotopic thermometry is also applicable to ascertaining the temperatures of diagenesis and low-grade metamorphism, and estimating the temperatures of active geothermal systems, both in the continental crust and on the ocean floor.

High-Temperature Thermometry

Stable isotope systems are frequently out of equilibrium in rocks that formed at high temperatures as a result of equilibration with a fluid phase following crystallization. This fact can be used to make inferences about the nature of rock-water interaction but does not help establish solidus or peak-metamorphic temperatures in igneous and metamorphic rocks. In systems where there is minimal water present, such as on the Moon, oxygen isotope thermometers yield meaningful temperatures. High-temperature results have been obtained on terrestrial lavas and mantle nodules. In metamorphic rocks, where there has been minimal fluid interaction, the newly calibrated thermometers hold promise for mineral-pairs with slow diffusion rates such as garnet-quartz and pyroxene-quartz.

High-Temperature Geothermometry: Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks

While paleothermometry focuses on sedimentary environments, oxygen isotope thermometry is equally critical for reconstructing the thermal history of igneous and metamorphic terrains. In these high-temperature systems ($>400^\circ\text{C}$), isotopic fractionation decreases, requiring highly sensitive mineral pairs.

Metamorphic Thermometry In metamorphic rocks, the Quartz-Magnetite and Quartz-Garnet pairs are standard geothermometers. Because oxygen diffusion is slower in garnet than in quartz or feldspar, garnets often retain the isotopic signature of peak metamorphism, resisting retrograde exchange during cooling. This “closure temperature” concept allows geologists to pinpoint the maximum temperature a rock body endured during orogenesis.

Igneous Petrogenesis For igneous systems, oxygen isotopes help distinguish between mantle-derived magmas and those contaminated by crustal material. A Plagioclase-Pyroxene pair is frequently used to estimate crystallization temperatures. However, researchers must be wary of sub-solidus hydrothermal alteration, which can disturb the primary isotopic equilibrium, particularly in feldspars. By analyzing refractory minerals like Zircon, which is extremely resistant to isotopic resetting, geologists can determine crystallization temperatures even in altered rocks.

What is a carbon isotope Thermometry

Inspection of the fractionation of 13C between species of carbon shows that in many cases it is strongly temperature-dependent. Two of these fractionations have been used as thermometers in metamorphic rocks.

The Calcite-Graphite δ13C Thermometer

Graphite coexists with calcite in a wide variety of metamorphic rocks and is potentially a useful thermometer at temperatures above 600°C. There are three calibrations currently in use. The calibration of Bottinga (1969) is based upon theoretical calculations and has the widest temperature range. Valley and O’Neil (1981) produced an empirical calibration based upon temperatures calculated from two-feldspar and ilmenite-magnetite thermometry, which is valid in the range 600-800°C. This curve is about 2‰ lower than the calculated curve of Bottinga (1969). Wada and Suzuki (1983) also calibrated the calcite-graphite and the dolomite-graphite thermometers empirically using temperatures obtained from dolomite-calcite solvus thermometry. Their calibration is valid in the range 400-680°C and is close to the Valley and O’Neil (1981) curve at high temperatures. Valley and O’Neil (1981) suggest that equilibrium is not reached between calcite and graphite at temperatures below 600°C. However, at temperatures above 600°C, organic carbon loses its distinctively negative δ13C signature in the presence of calcite.

The CO2-Graphite Thermometer

The carbon isotope composition of CO2 in fluid inclusions and that of coexisting graphite can also be used as a thermometer. The exchange was calibrated by Bottinga (1969). The method was used by Jackson et al. (1988), who obtained equilibration temperatures close to the peak of metamorphism from CO2-rich inclusions in quartz and graphite in granulite facies gneisses from south India.

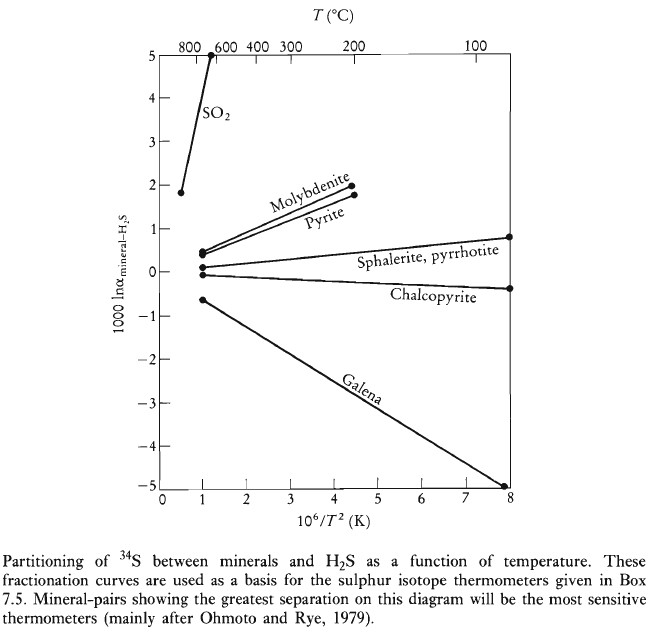

Sulfur Isotope Thermometry

There are a number of theoretical and experimental determinations of the fractionation of δ34S between coexisting sulfide phases as a function of temperature. Sulfide-pair thermometers derived from these results are available. However, the partitioning of sulfur isotopes between sulfides is not a particularly sensitive thermometer and requires precise isotopic determinations. More extensive δ34S fractionation occurs between sulfide and sulfate phases.

In common with oxygen and carbon isotopes, sulfide mineral pairs, and sulfide-sulfate mineral pairs are not necessarily in isotopic equilibrium. This is particularly the case at low temperatures or where the isotopic composition of the mineralizing fluid has varied during mineralization. The attainment of isotopic equilibrium can best be demonstrated by determining temperature estimates between three coexisting minerals, and if the two temperature estimates agree, isotopic equilibrium may be assumed. If this approach is not possible, then clear textural evidence for the attainment of equilibrium should be present before the results are accepted.

Sulphur Isotope Fractionation Between H₂S and Sulphur Compounds

| Mineral | A | B | Temperature Range (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anhydrite/gypsum | 6.463 | 0.56 ± 0.5 | 200–400 | Ohmoto and Lasaga (1982) |

| Baryte | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 200–400 | Miyoshi et al. (1984) |

| Molybdenite | 0.45 ± 0.10 | Uncertain | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) | |

| Pyrite | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 200–700 | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) | |

| Sphalerite | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 50–705 | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) | |

| Pyrrhotite | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 50–705 | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) | |

| Chalcopyrite | -0.05 ± 0.08 | 200–600 | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) | |

| Bismuthinite | -0.67 ± 0.07 | 250–600 | Bente and Nielsen (1982) | |

| Galena | -0.63 ± 0.05 | 50–700 | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) | |

| SO₂ | 4.70 | -0.5 ± 0.5 | 350–1050 | Ohmoto and Rye (1979) |