Chronostratigraphy

Introduction

- Lithology (Lithostratigraphy): The stratigraphic units described in the preceding lectures are rock units distinguished by:

- Magnetic characteristics

- Fossil content (Biostratigraphy)

- Seismic reflection characteristics

To interpret Earth’s history, stratigraphic units must be related to geologic time. The ages of rock units must be known.

- Chronostratigraphy: Establishing the time relationship among rock units is called chronostratigraphy, and stratigraphic units defined and delineated based on time are geologic time units.

GSSP

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is an internationally agreed-upon reference point on a stratigraphic section that defines the lower boundary of a stage on the geologic time scale. A geologic section must fulfill a set of criteria to be adapted as a GSSP by the ICS. The criteria are:

- A GSSP must define the lower boundary of a geologic stage.

- The lower boundary must be defined using a primary marker (usually the first appearance datum of a fossil species).

- There should also be secondary markers (other fossils, chemical, geomagnetic reversal).

- The horizon in which the marker appears should have minerals that can be radiometrically dated.

- The marker must have regional and global correlation in outcrops of the same age.

- The marker should be independent of facies.

- The outcrop must have adequate thickness.

- Sedimentation must be continuous without any changes in facies.

- The outcrop should be unaffected by tectonic and sedimentary movements, and metamorphism.

- The outcrop must be accessible to research and free to access. This includes being located where it can be visited quickly (international airport and good roads), kept in good condition (ideally a national reserve), inaccessible terrain, extensive enough to allow repeated sampling, and open to researchers of all nationalities.

Once a GSSP boundary has been agreed upon, a “golden spike” is driven into the geologic section to mark the precise boundary for future geologists (though in practice the “spike” need neither be golden nor an actual spike). The first stratigraphic boundary was defined in 1977 by identifying the Silurian-Devonian boundary with a bronze plaque at a locality called Klonk, northeast of the village of Suchomasty in the Czech Republic. GSSPs are also sometimes referred to as Golden Spikes.

Geologic Time Units

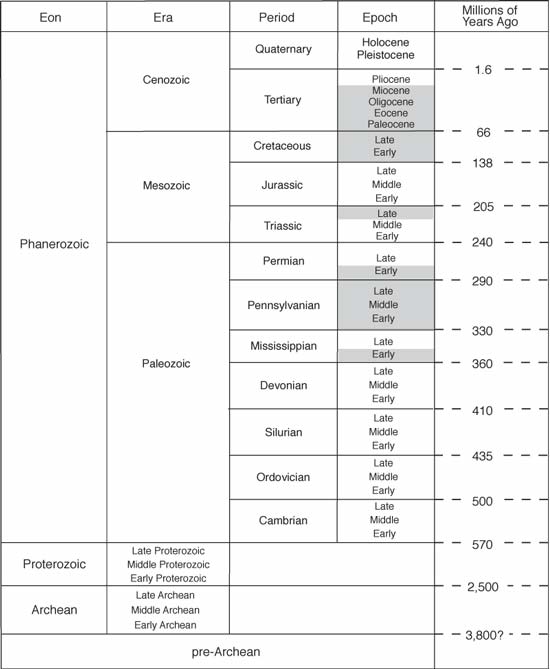

Geologic Time Units are stratigraphic units defined and delineated based on time. The reference rock bodies for geologic time units are isochronous units, meaning they are rock units formed during the same period and everywhere bounded by synchronous surfaces, which are surfaces on which every point has the same age. The North American Stratigraphic Code and The International Stratigraphic Guide recognize two fundamental types of isochronous geologic time units:

| Chronostratigraphic Units | Division of Time |

| Erathem | Era |

| System | Period |

| Series | Epoch |

| Stage | Age |

| Chronozone | Chron |

- Chronostratigraphic Units: Tangible bodies of rock that geologists select to serve as reference sections, or material referents, for all rocks formed during the same time interval. For example, the interval from about 275-250 million years ago is called the Permian Period and is represented by rocks of the Permian System located in the Province of Perm, Russia.

- Geochronologic Units: Divisions of time distinguished based on the rock record as expressed by chronostratigraphic units. They are not in themselves stratigraphic units. If the distinction between these two types of units seems somewhat confusing, the following illustration may help to clarify the difference. Chronostratigraphic units have been likened to the sand that flows through an hourglass during a certain period. By contrast, corresponding geochronologic units can be compared to the interval of time during which the sand flows.

Chronostratigraphic Unit

- Chronostratigraphic Unit: An isochronous body of rock that serves as the material reference for all rocks formed during the same periods; it is always based on a material reference unit, or stratotype, which is a biostratigraphic, lithostratigraphic, or magnetopolarity unit. The fundamental chronostratigraphic unit is the System.

- Eonothem: The highest-ranking chronostratigraphic unit; three recognized:

- Phanerozoic, encompassing the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic erathems, and the

- Proterozoic and

- Archean, which together make up the Precambrian.

- Erathems: Subdivisions of an eonothem; none in the Precambrian; the Phanerozoic erathems, names originally chosen to reflect major changes in the development of life on Earth, are the Paleozoic (“old life”), Mesozoic (“intermediate life”), and Cenozoic (“recent life”).

- System: The primary chronostratigraphic unit of worldwide major rank (e.g., Permian System, Jurassic System); can be subdivided into subsystems or grouped into super systems but most commonly are divided completely into units of the next lower rank (series).

- Series: A subdivision of a system; systems are divided into two to six series (commonly three); generally take their name from the system by adding the appropriate adjective “Lower,” “Middle,” or “Upper” to the system name (e.g., Lower Jurassic Series, Middle Jurassic Series, Upper Jurassic Series); useful for chronostratigraphic correlation within provinces; many can be recognized worldwide.

- Stage: Smaller scope and rank than series; very useful for intraregional and intracontinental classification and correlation; many stages also recognized worldwide; may be subdivided into substages.

- Chronozone: The smallest chronostratigraphic unit; its boundaries may be independent of those of ranked stratigraphic units.

- Eonothem: The highest-ranking chronostratigraphic unit; three recognized:

- Higher-ranking units are groupings of systems, and lower-ranking units are subdivisions of systems.

Geochronologic Unit

Geochronologic units are divisions of time distinguished based on the rock record as expressed by chronostratigraphic units; not an actual rock unit, but correspond to the interval of time during which an established chronostratigraphic unit was deposited or formed; thus, the beginning of a geochronologic unit corresponds to the time of deposition of the bottom of the chronostratigraphic unit upon which it is based and the ending corresponds to the time of deposition of the top of the refer. The fundamental geochronologic unit is thus the period time equivalent of a system.

| Geochronologic Unit | Corresponding Geochronostratigraphic Unit |

| Eon | Eonothem |

| Era | Erathem |

| Period | System |

| Epoch | Series |

| Age | Stage |

| Chron | Chronozone |

Geochronometric Units

Geochronometric units are pure time units. They are not based on the periods of designated chronostratigraphic stratotypes but are simply time divisions of an appropriate magnitude or scale, with arbitrarily chosen boundaries. At this time, a geochronometric time scale is used to express the ages of Precambrian rocks because no globally recognized and accepted chronostratigraphic scale has been developed for these rocks.

- A geochronometric time scale is used to express the ages of Precambrian rocks because no globally recognized and accepted chronostratigraphic scale has been developed for these rocks.

- The nomenclature of Phanerozoic chronostratigraphic units is commonly used throughout the world. Precambrian rocks are divided into the Archean and Proterozoic; however, no scheme for further subdivision of the Precambrian is globally accepted.

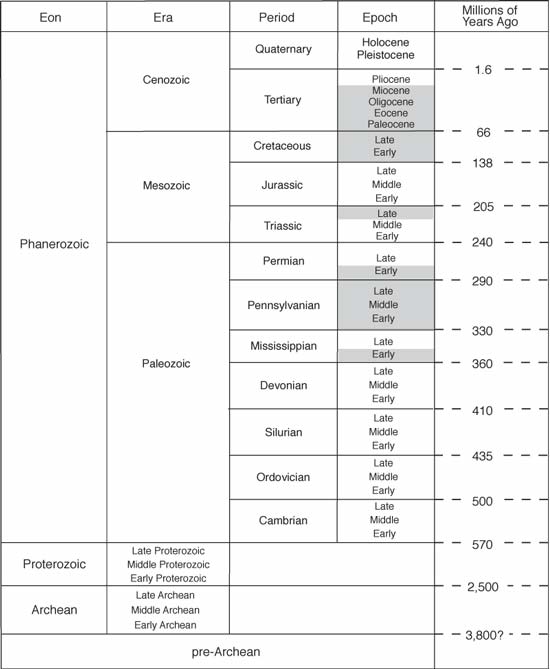

The Geologic Time Scale

Purpose of Geological Time Scale: The ultimate aim of creating a standardized geologic time scale is to establish a hierarchy of chronostratigraphic units of international scope that can serve as a standard reference to which the ages of rocks everywhere in the world can be related. Establishing the relative ordering of events in Earth’s history is the main contribution that geology makes to our understanding of time.

Development of the Geologic Time Scale:

- Chronostratigraphic Scale: Geologists have been working for more than 200 years to develop a systematic scheme for a global time-stratigraphic classification of rock units. This slow process has evolved through two fundamental stages of development:

- Determining time-stratigraphic relationships from local stratigraphic sections by applying the principle of superposition, supplemented by fossil control and, more recently, radiometric ages.

- Using these local stratigraphic sections as a basis for establishing a composite international chronostratigraphic scale, which serves as the material reference for constructing a standardized international geologic time scale.

The chronostratigraphic scale has units and boundaries based on physical divisions of the rock record, but it is not in itself a time scale. To function as a geologic time scale for expressing the age of a rock unit or a geologic event, the chronostratigraphic scale must be converted to a geochronologic scale consisting of units that represent intervals of time rather than bodies of rock that formed during a specified time interval.

The geologic time scale is derived from the chronostratigraphic scale by substituting for chronostratigraphic units the corresponding geochronologic units. Thus, the geologic time scale is expressed in eras, periods, epochs, ages, and chrons rather than erathems, systems, series, stages, and chronozones. The subdivision boundaries of the geologic time scale are calibrated in absolute ages true geochronometric scale, which is based purely on time without regard to the rock record. By contrast, the subdivisions of the Phanerozoic time scale are of unequal length, because they are based on chronostratigraphic units that were deposited during unequal intervals of time.

Geochronologic (Time) Scale

Numerical & Relative Dates

- Numerical: During the late 1800s and early 1900s, attempts were made to determine Earth’s age. Although some of the methods appeared promising at the time, none of those early efforts proved to be reliable.

- Scientists were seeking a numerical date (Absolute age). Such dates specify the actual number of years that have passed since an event occurred.

- Today, our understanding of radioactivity allows us to accurately determine numerical dates for rocks that represent important events in Earth’s distant past. Before the discovery of radioactivity, geologists had no reliable method of numerical dating and had to rely solely on relative dating.

- Relative Dates: When we place rocks in their proper sequence of formation—indicating which formed first, second, third, and so on—we are establishing relative dates. Such dates cannot tell us how long ago something took place, only that it followed one event and preceded another.

Calibrating the Geologic Time Scale

Placing strata in stratigraphic order in terms of their relative ages has been the guiding principle used by stratigraphers in constructing the geologic time scale. Relative ordering was determined by applying the principle of superposition, aided by the use of fossils. The principal method for determining the absolute ages of rocks is based on the decay of radioactive isotopes of elements in minerals. Other methods of determining the absolute passage of geologic time include:

- Counting lake-sediment varves, which are presumed to represent annual sediment accumulations.

- Growth increments in the shells of some invertebrate organisms.

- Growth rings in trees.

- Milankovitch climate cycles in sediments.

Thus, the major tools for finding ages of sediments to calibrate the geologic time scale are relative age determinations by use of fossils-biochronology and absolute age estimates based on isotopic decay-radiochronology.

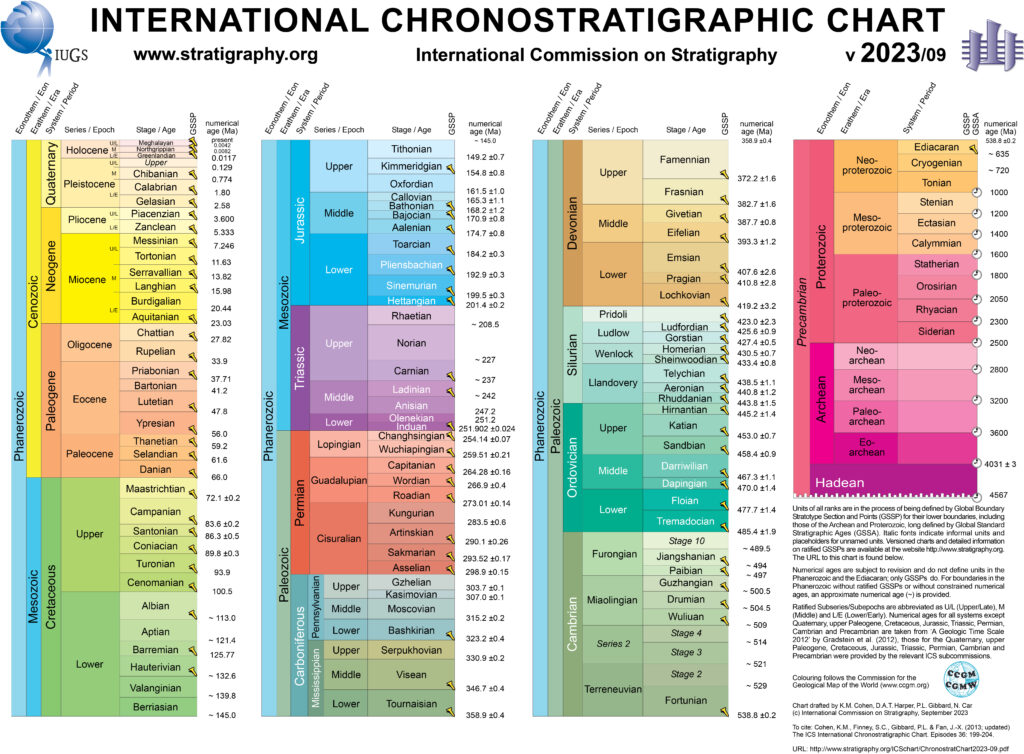

Radiochronology: Calibrating by Absolute Ages

Radiochronology is based on the principle that radiogenic minerals such as uranium-235 and potassium-40 decay spontaneously at a fixed rate to a “daughter” product. An unstable (radioactive) isotope is referred to as the parent, and the isotopes resulting from the decay of the parent are termed the daughter products. Uranium-238, one of the most important isotopes for geologic dating, when the radioactive parent, uranium-238 (atomic number 92, mass number 238) decays, it follows a number of steps, emitting a total of 8 alpha particles and 6 electrons before finally becoming the stable daughter product lead-206 (atomic number 82, mass number 206).

The age of a radiogenic mineral can be calculated from the measured ratio of parent radionuclide to daughter product in the mineral, by use of the known decay rate of the parent material. The decay rate is commonly expressed as the half-life of the radioactive isotope (i.e., the time required for one-half of the parent material to decay to the daughter product). The number of atoms of the parent radioactive material and the inert daughter product are measured by a mass spectrometer.

The equation for calculating radiometric age is:

t=λ1ln(ND−D0+1)

N is the number of parent atoms of an element (e.g., uranium) present in any given amount of the element,

ln is log base

e,

D is the total number of daughter atoms (e.g., lead),

D0 is the number of original daughter atoms, and

λ is the decay constant, which is calculated from the relationship:

λ=T1/20.693

T1/2 is the half-life of the radioactive element.

Radiometric Methods

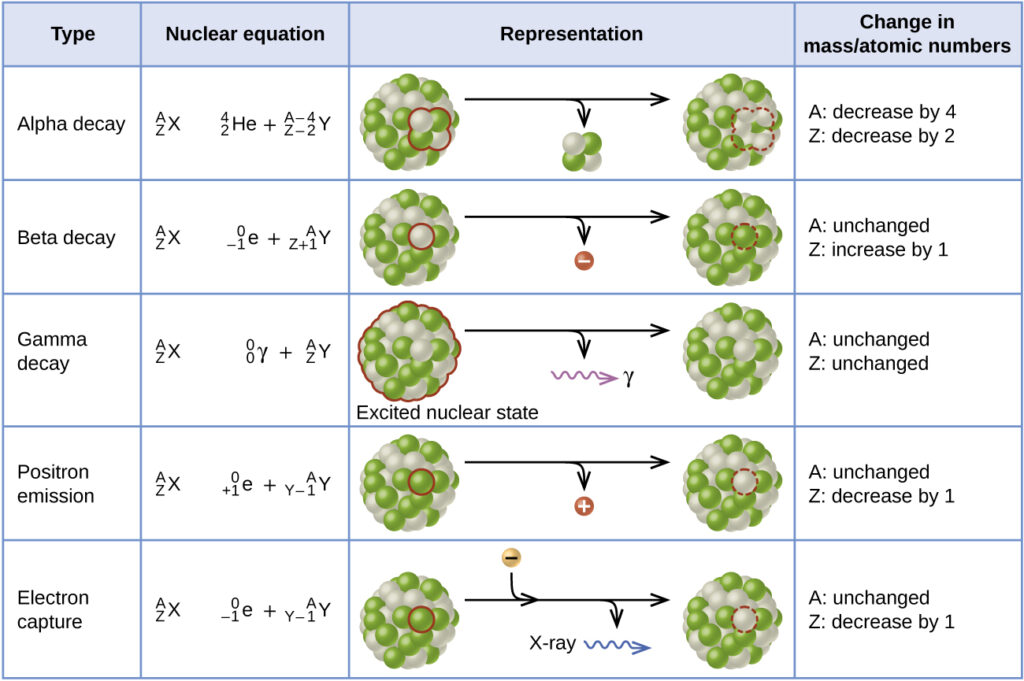

• Principal Methods: Some of the most useful radionuclides for estimating absolute ages and the minerals, rocks, and organic materials most suitable for age determination are shown in table.

| Parent Nuclide | Daughter Nuclide | Half-life (years) | Approximate Useful Dating Range (years B.P.) | Materials Commonly Used for Dating |

| Carbon-14 | Nitrogen-14 | 5730 | <~40,000 | Wood, charcoal, CaCO₃ shells |

| Protactinium-231 (daughter nuclide of uranium-235) | Actinium-227 | 32,480 | <~150,000 | Deep-sea sediment, aragonite corals |

| Thorium-230 (daughter nuclide of uranium 238/234) | Radium-226 | 75,200 | <~250,000 | Deep-sea sediment, aragonite corals |

| Uranium-238 | Lead-206 | 4,500 million | 10 -> 4500 million | Zircon, monazite, sphene, apatite, uranium/thorium minerals |

| Uranium-238 | Spontaneous fission tracks | 4,500 million | <~65 million | Volcanic glass, zircon, apatite, sphene, glassy igneous materials |

| Uranium-235 | Lead-207 | 710 million | 10 -> 4500 million | Zircon, apatite, monazite, sphene, uranium/thorium minerals |

| Potassium-40 | Argon-40 | 1,250 million | 10 -> 4500 million | Micas, biotite, muscovite, hornblende, glauconite, whole volcanic rock |

| Rubidium-87 | Strontium-87 | 48 billion | 10 -> 4500 million | Micas, K-feldspar, whole volcanic rock |

| Samarium-147 | Neodymium-143 | 106 billion | >200 million | Pyroxene, plagioclase, garnet, apatite, sphene |

| Lutetium-176 | Hafnium-176 | 35 billion | >200 million | Pyroxene, plagioclase, garnet, apatite, sphene |

Important Points

- Carbon-14 Method: Applied to direct dating of very young sediments.

- Protactinium-231 and Thorium-230 Methods: Applied to direct dating of sediments ranging in age to about 250,000 years.

- Potassium/Argon Method: Widely used because it can be applied to a number of minerals common in igneous and metamorphic rocks, giving generally reliable results. It can be used for dating plutonic, igneous, volcanic, and metamorphic rocks (as metamorphism resets the radioactive clock), and even some sedimentary minerals (e.g., glauconite). The principal problem with the potassium/argon method is that the decay product, argon-40, is a gas that can leak out of a crystal.

- Samarium/Neodymium and Lutetium/Hafnium Methods: Less commonly used dating techniques that may be applied to some rocks less amenable to dating by conventional methods. Samarium and lutetium are rare earth elements with long half-lives, making them useful for dating very old (Precambrian) rocks.

- Fission-Track Dating: Relies on counting fission tracks in minerals such as zircon. Emission of charged particles from decaying nuclei causes disruption of crystal lattices, creating tracks, which can be seen and counted under a microscope. The older the mineral, the more tracks are present.

Radiochronology of Sedimentary Rocks

Terrigenous minerals in sedimentary rocks are not useful for radiochronology because they yield ages for the parent rocks, not the time of deposition of the sediment. Although a few marine minerals, such as glauconite, can be used for direct dating of sedimentary rocks, much of the geologic time scale has been calibrated by indirect methods. These methods estimate ages of sedimentary rocks based on their relationship to igneous or metamorphic rocks whose ages can be determined by radiochronology.

The types of rocks most useful for isotopic calibration of the geologic time scale are described in the table below.

| Type of Rock | Stratigraphic Relationship | Reliability of Age Data |

| Volcanic rock (lava flows and ash falls) | Interbedded with ‘contemporaneous’ sedimentary rocks | Give actual ages of sedimentary rocks in close stratigraphic proximity above and below volcanic layers |

| Plutonic igneous rocks | Intrude (cut across) sedimentary rocks | Give minimum ages for the rocks they intrude |

| Metamorphosed sedimentary rocks | Lie unconformably beneath sedimentary rocks | Give maximum ages for overlying sedimentary rocks |

| Sedimentary rocks containing contemporary organic remains (fossils, wood) | Constitute the rocks whose ages are being determined | Give minimum ages for metamorphosed sedimentary rocks |

| Sedimentary rocks containing authigenic minerals such as glauconite | Lie unconformably beneath non-metamorphosed sedimentary rocks | Give maximum ages for the overlying non-metamorphosed sedimentary rocks |

The only materials in sedimentary rocks that can be used for direct radiochronology are organic remains (wood, calcium carbonate fossils, and other such remains) that were deposited with the sediment and authigenic minerals that formed in the sediment while still on the seafloor or shortly after burial.

Principal Methods for Direct Radiochronology of Sedimentary Rocks:

- Carbon-14 Technique: Used for organic materials such as wood, peat, charcoal, bone, leaves, and the CaCO₃ shells of marine organisms. This method has been extensively used for estimating the ages of archaeological materials, but its application in geology is limited to Quaternary geology because of the very short useful age range of the method.

- Potassium-Argon and Rubidium-Strontium Techniques: Applied to glauconites.

- Thorium-230 Technique: Used for ocean floor sediments.

- Thorium-230/Protactinium-231 Technique: Applied to fossils and sediments.

Responses