Chapter Overview

- The atmosphere and the ocean are an interdependent system.

- Earth has seasons because it is tilted on its axis.

- There are three major wind belts in each hemisphere.

- The Coriolis effect influences atmosphere and ocean behavior.

- Oceanic climate patterns are related to solar energy distribution.

Atmosphere and Oceans

- Solar energy heats Earth, generates winds.

- Winds drive ocean currents.

- Extreme weather events may be related to ocean.

- Global warming affects oceans.

Earth’s Seasons

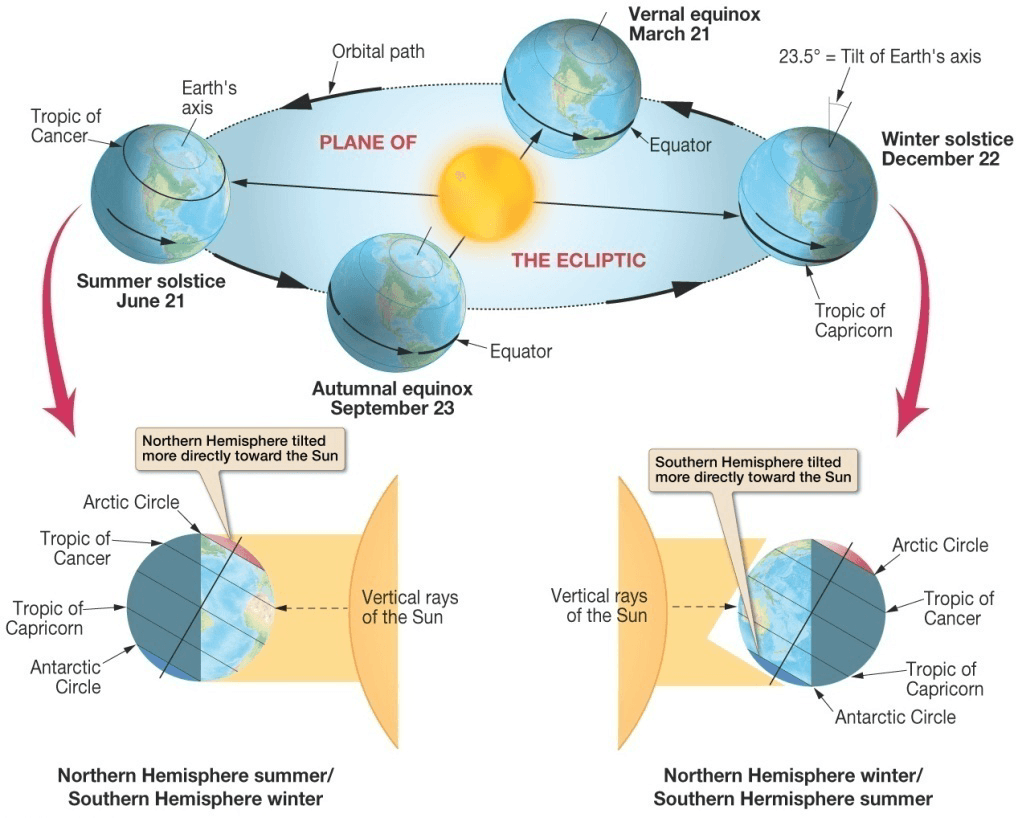

- Earth’s axis of rotation is tilted 23.5 degrees with respect to plane of the ecliptic.

– Plane of the ecliptic

– plane traced by Earth’s orbit around the Sun - Earth’s orbit is slightly elliptical.

orbit (red line) and a perfectly circular orbit (yellow dashed line). View is directly above Earth’s plane of the ecliptic; Earth’s elliptical orbit is exaggerated for clarity (not to scale).

- Earth’s tilt, not orbit, causes seasons.

At the vernal equinox (vernus = spring; equi = equal, noct = night), which occurs on or about March 21, the Sun is directly overhead along the equator. During this time, all places in the world experience equal lengths of night and day (hence the name equinox). In the Northern Hemisphere, the vernal equinox is also known as the spring equinox.

At the summer solstice (sol = the Sun, stitium = a stoppage), which occurs on or about June 21, the Sun reaches its most northerly point in the sky, directly overhead along the Tropic of Cancer, at 23.5 degrees north latitude. To an observer on Earth, the noonday Sun reaches its northernmost or southernmost position in the sky at this time and appears to pause—hence the term solstice—before beginning its next six-month cycle.

At the autumnal equinox (autumnus = fall), which occurs on or about September 23, the Sun is directly overhead along the equator again. In the Northern Hemisphere, the autumnal equinox is also known as the fall equinox.

At the winter solstice, which occurs on or about December 22, the Sun is directly overhead along the Tropic of Capricorn, at 23.5 degrees south latitude. In the Southern Hemisphere, the seasons are reversed. Thus, the winter solstice is the time when the Southern Hemisphere is most directly facing the Sun, which marks the beginning of the Southern Hemisphere summer.

Because Earth’s rotational axis is tilted 23.5 degrees, the Sun’s declination (angular distance from the equatorial plane) varies between 23.5 degrees north and 23.5 degrees south of the equator on a yearly cycle. As a result, the region between these two latitudes (called the tropics) receives much greater annual radiation than polar areas.

Seasonal changes in the angle of the Sun and the length of day profoundly influence Earth’s climate. In the Northern Hemisphere, for example, the longest day occurs on the summer solstice and the shortest day on the winter solstice.

Daily heating of Earth also influences climate in most locations. Exceptions to this pattern occur north of the Arctic Circle (66.5 degrees north latitude) and south of the Antarctic Circle (66.5 degrees south latitude), where at certain times of the year, daily cycles of daylight and darkness are absent.

For instance, during the Northern Hemisphere winter, the area north of the Arctic Circle receives no direct solar radiation and can experience up to six months of darkness. At the same time, the area south of the Antarctic Circle receives continuous radiation (“midnight Sun”), experiencing up to six months of light. Half a year later, during the Northern Hemisphere summer (Southern Hemisphere winter), the situation is reversed.

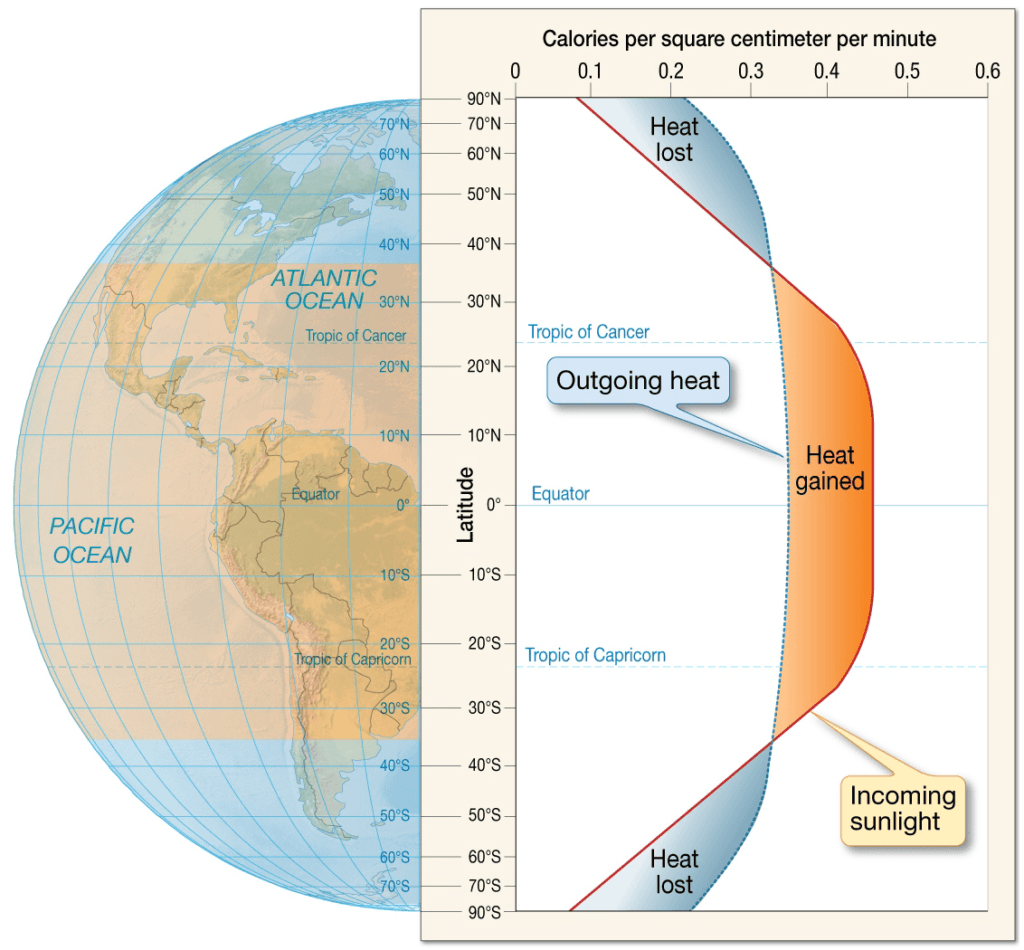

Distribution of Solar Energy

Solar footprint: Most of the time in the equatorial region, the Sun is directly overhead. At low latitudes, sunlight strikes at a high angle, meaning solar radiation is concentrated in a relatively small area . Closer to the poles, sunlight strikes at a low angle, and the same amount of radiation is spread over a larger area .

Atmospheric absorption: Earth’s atmosphere absorbs some radiation, so less radiation reaches Earth’s surface at high latitudes compared to low latitudes. This is because sunlight must pass through more atmosphere at high latitudes.

Albedo: The albedo (from “albus” meaning white) refers to the percentage of incident radiation that is reflected back to space. This varies depending on the material. For example, thick sea ice covered by snow reflects up to 90% of incoming solar radiation, giving it a high albedo. This results in a larger proportion of radiation being reflected back into space in ice-covered high latitudes compared to low latitudes, which lack substantial ice. Other Earth materials such as ocean, soil, vegetation, sand, and rock have much lower albedo values than ice. On average, Earth’s surface has an albedo of about 30%.

Reflection of incoming sunlight: The angle at which sunlight strikes the ocean surface determines how much radiation is absorbed and how much is reflected. When the Sun shines down on a smooth sea from directly overhead, only 2% of the radiation is reflected. However, if the Sun is just 5 degrees above the horizon, 40% of the sunlight is reflected back into the atmosphere. Therefore, the ocean reflects more radiation at high latitudes than at low latitudes

the higher latitudes receive much less solar energy.

Sun Elevation and Solar Absorption

| REFLECTION AND ABSORPTION OF SOLAR ENERGY RELATIVE TO THE ANGLE OF INCIDENCE ON A FLAT SEA | |||||

| Elevation of the Sun above the horizon | 90° | 60° | 30° | 15° | 5° |

| Reflected radiation (%) | 2 | 3 | 6 | 20 | 40 |

| Absorbed radiation (%) | 98 | 97 | 94 | 80 | 60 |

Oceanic Heat Flow

- High latitudes – more heat lost than gained

– Ice has high albedo

– Low solar ray incidence - Low latitudes – more heat gained than lost

lost by the oceans balance each other on a global scale, whereby the excess heat from low latitudes is transferred to heat-deficient high latitudes by both oceanic and atmospheric circulation

Physical Properties of the Atmosphere

Composition

- Mostly nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2)

- Other gases significant for heattrapping properties

Temperature Variation in the Atmosphere

Intuitively, it seems logical that the higher one goes in the atmosphere, the warmer it should be since it’s closer to the Sun. However, as unusual as it seems, the atmosphere is actually heated from below. That is because the Sun’s energy passes through the Earth’s atmosphere and warms Earth’s surface (both land and water), which in turn reradiates this energy back into the atmosphere as heat.

the names of atmospheric layers.

The lowermost portion of the atmosphere, which extends from the surface to about 12 kilometers (7 miles), is called the troposphere (tropo = turn, sphere = a ball) and is where all weather is produced. The troposphere gets its name because of the abundance of mixing that occurs within this layer of the atmosphere, mostly as a result of being heated from below. Within the troposphere, temperature gets cooler with altitude to the point that at high altitudes, the air temperature is well below freezing. If you have ever flown in a jet airplane, for instance, you may have noticed that any water on the wings or inside your window freezes during a high-altitude flight.

Density Variations in the Atmosphere

It may seem surprising that air has density, but since air is composed of molecules, it certainly does. Temperature has a dramatic effect on the density of air. At higher temperatures, for example, air molecules move more quickly, take up more space, and density is decreased. Thus, the general relationship between density and temperature is as follows:

- Warm air is less dense, so it rises; this is commonly expressed as “heat rises.”

- Cool air is more dense, so it sinks.

Figure shows how a radiator (heater) uses convection to heat a room. The heater warms the nearby air and causes it to expand. This expansion makes the air less dense, causing it to rise. Conversely, a cold window cools the nearby air and causes it to contract, thereby becoming more dense, which causes it to sink. A convection cell (con = with, vect = carried) forms, composed of the rising and sinking air moving in a circular fashion.

Water Vapor in Air

- Partly dependent upon air temperature

– Warm air typically moist

– Cool air typically dry - Influences density of air

Atmospheric Pressure

Atmospheric pressure is 1.0 atmosphere (14.7 pounds per square inch) at sea level and decreases with increasing altitude. Atmospheric pressure depends on the weight of the column of air above. For instance, a tall column of air produces higher atmospheric pressure than a short column of air. An analogy to this is water pressure in a swimming pool: The taller the column of water above, the higher the water pressure. Thus, the highest pressure in a pool is at the bottom of the deep end.

Similarly, the tall column of air at sea level means air pressure is high at sea level and decreases with increasing elevation. When sealed bags of potato chips or pretzels are taken to a high elevation, there is a shorter column of air overhead, and the atmospheric pressure is much lower than where the bags were sealed. This may cause the bags to swell and sometimes burst. You may also have experienced this change in pressure when your ears “popped” during the takeoff or landing of an airplane, or while driving on steep mountain roads.

Changes in atmospheric pressure cause air movement as a result of changes in the molecular density of the air. The general relationship is shown in Figure, which indicates that:

- A column of cool, dense air causes high pressure at the surface, which will lead to sinking air (movement toward the surface and compression).

- A column of warm, less dense air causes low pressure at the surface, which will lead to rising air (movement away from the surface and expansion)

Movement of the Atmosphere

Air always moves from high-pressure regions toward low-pressure regions. This moving air is called wind.

Movements in the Air

- Fictional nonspinning Earth

- Air rises at equator (low pressure)

- Air sinks at poles (high pressure)

- Air flows from high to low pressure

- One convection cell or circulation cell

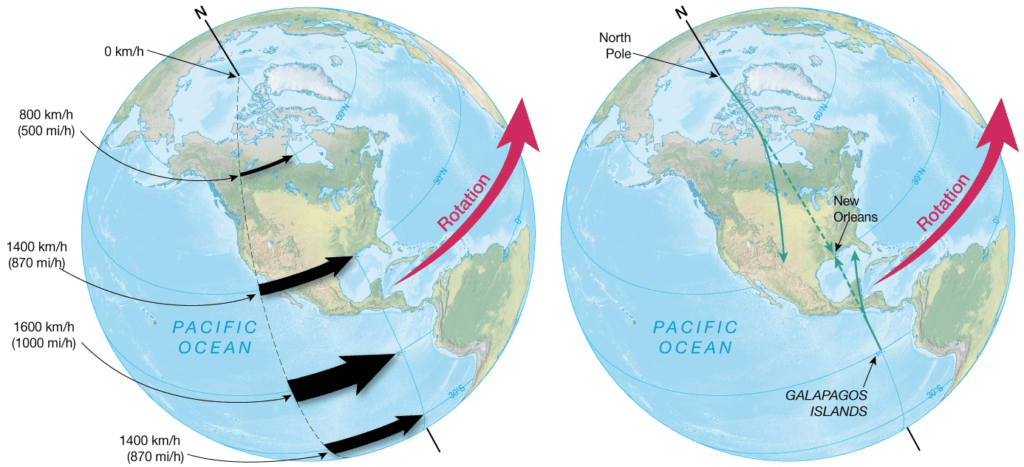

The Coriolis Effect

- Deflects path of moving object from viewer’s perspective

- To right in Northern Hemisphere

- To left in Southern Hemisphere

- Due to Earth’s rotation

- Zero at equator

- Greatest at poles

- Change in Earth’s rotating velocity with latitude

– 0 km/hour at poles

– More than 1600 km/hour (1000 miles/hour) at equator - Greatest effect on objects that move long distances across latitudes

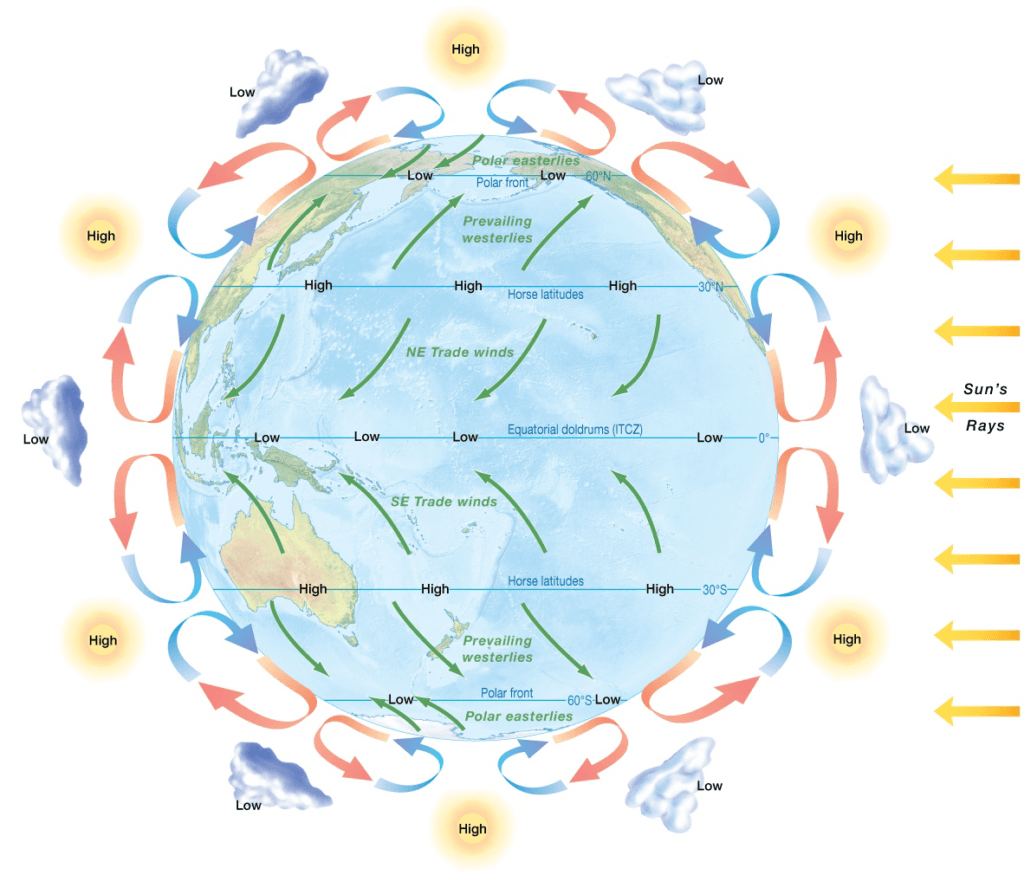

Global Atmospheric Circulation

- Circulation Cells – one in each hemisphere

– Hadley Cell: 0–30 degrees latitude

– Ferrel Cell: 30–60 degrees latitude

– Polar Cell: 60–90 degrees latitude - Rising and descending air from cells generate high and low pressure zones

- High pressure zones – descending air

– Subtropical highs – 30 degrees latitude

– Polar highs – 90 degrees latitude

– Clear skies - Low pressure zones – rising air

– Equatorial low – equator

– Subpolar lows – 60 degrees latitude

– Overcast skies with abundant precipitation

the wind belts (blue lettering), surface atmospheric pressures (high or low), and resulting typical weather (Sun or clouds).

Global Wind Belts

The lowermost portion of the circulation cells—that is, the part that is closest to the surface—generates the major wind belts of the world. The masses of air that move across Earth’s surface from the subtropical high-pressure belts toward the equatorial low-pressure belt constitute the trade winds. These steady winds are named from the term to blow trade, which means to blow in a regular course.

If Earth did not rotate, these winds would blow in a north–south direction. In the Northern Hemisphere, however, the northeast trade winds curve to the right due to the Coriolis effect and blow from northeast to southwest. In the Southern Hemisphere, the southeast trade winds curve to the left due to the Coriolis effect and blow from southeast to northwest.

Some of the air that descends in the subtropical regions moves along Earth’s surface to higher latitudes as the prevailing westerly wind belts. Because of the Coriolis effect, the prevailing westerlies blow from southwest to northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from northwest to southeast in the Southern Hemisphere.

Air moves away from the high pressure at the poles, too, producing the polar easterly wind belts.

- Portion of global circulation cells closest to surface generate winds

- Trade winds – From subtropical highs to equator

– Northeast trades in Northern Hemisphere

– Southeast trades in Southern Hemisphere - Prevailing westerly wind belts – from 30–60 degrees latitude

- Polar easterly wind belts – 60–90 degrees latitude

- Boundaries between wind belts

– Doldrums or Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) – at equator

– Horse latitudes – 30 degrees

– Polar fronts – 60 degrees latitude

Characteristics of Wind Belts and Boundaries

| characteristics of wind belts and boundaries | |||

| Region (north or south latitude) | Name of wind belt or boundary | Atmospheric pressure | Characteristics |

| Equatorial (0–5 degrees) | Doldrums (boundary) | Low | Light, variable winds. Abundant cloudiness and much precipitation. Breeding ground for hurricanes. |

| 5–30 degrees | Trade winds (wind belt) | — | Strong, steady winds, generally from the east. |

| 30 degrees | Horse latitudes (boundary) | High | Light, variable winds. Dry, clear, fair weather with little precipitation. Major deserts of the world. |

| 30–60 degrees | Prevailing westerlies (wind belt) | — | Winds generally from the west. Brings storms that influence weather across the United States. |

| 60 degrees | Polar front (boundary) | Low | Variable winds. Stormy, cloudy weather year round. |

| 60–90 degrees | Polar easterlies (wind belt) | — | Cold, dry winds generally from the east. |

| Poles (90 degrees) | Polar high pressure (boundary) | High | Variable winds. Clear, dry, fair conditions, cold temperatures, and minimal precipitation. Cold deserts. |

Idealized Three-Cell Model

- More complex in reality due to

– Tilt of Earth’s axis and seasons

– Lower heat capacity of continental rock vs. seawater

– Uneven distribution of land and ocean

Weather vs. Climate

- Weather – conditions of atmosphere at particular time and place

- Climate – long-term average of weather

- Ocean influences Earth’s weather and climate patterns.

Winds

- Cyclonic flow

– Counterclockwise around a low in Northern Hemisphere

– Clockwise around a low in Southern Hemisphere - Anticyclonic flow

– Clockwise around a low in Northern Hemisphere

– Counterclockwise around a low in Southern Hemisphere

Sea and Land Breezes

- Differential solar heating is due to different heat capacities of land and water.

- Sea breeze

– From ocean to land - Land breeze

– From land to ocean

Storms and Air Masses

- Storms – disturbances with strong winds and precipitation

- Air masses – large volumes of air with distinct properties

- Land air masses dry

- Marine air masses moist

Fronts

- Fronts – boundaries between air masses

- Warm front – Contact where warm air mass moves to colder area

- Cold front – Contact where cold air mass moves to warmer area

- Storms typically develop at fronts.

- Jet Stream – narrow, fast-moving, easterly air flow

– At middle latitudes just below top of troposphere

– May cause unusual weather by steering air masses

Tropical Cyclones (Hurricanes)

- Large rotating masses of low pressure

- Strong winds, torrential rain

- Classified by maximum sustained wind speed

- Typhoons – alternate name in North Pacific

- Cyclones – name in Indian Ocean

Hurricane Origins

- Low pressure cell

- Winds feed water vapor

– Latent heat of condensation - Air rises, low pressure deepens

- Storm develops

Hurricane Development

- Tropical Depression

– Winds less than 61 km/hour (38 miles/hour) - Tropical Storm

– Winds 61–120 km/hour (38–74 miles/hour) - Hurricane or tropical cyclone

– Winds above 120 km/hour (74 miles/hour)

Saffir-Simpson Scale of Hurricane Intensity

| The saffir-simpson scale of hurricane intensity | |||||

| Category | Wind speed | Typical storm surge (sea level height above normal) | Damage | ||

| km/hr | mi/hr | meters | feet | ||

| 1 | 120–153 | 74–95 | 1.2–1.5 | 4–5 | Minimal: Minor damage to buildings |

| 2 | 154–177 | 96–110 | 1.8–2.4 | 6–8 | Moderate: Some roofing material, door, and window damage; some trees blown down |

| 3 | 178–209 | 111–130 | 2.7–3.7 | 9–12 | Extensive: Some structural damage and wall failures; foliage blown off trees and large trees blown down |

| 4 | 210–249 | 131–155 | 4.0–5.5 | 13–18 | Extreme: More extensive structural damage and wall failures; most shrubs, trees, and signs blown down |

| 5 | >250 | >155 | >5.8 | >19 | Catastrophic: Complete roof failures and entire building failures common; all shrubs, trees, and signs blown down; flooding of lower floors of coastal structures |

Hurricanes

- About 100 worldwide per year

- Require

– Ocean water warmer than 25°C (77°F)

– Warm, moist air

– The Coriolis effect - Hurricane season is June 1–November 30

- Hurricane Anatomy

- Diameter typically less than 200 km (124 miles)

– Larger hurricanes can be 800 km (500 miles) - Eye of the hurricane

– Low pressure center - Spiral rain bands with intense rainfall and thunderstorms

Impact of Other Factors

- Warmer waters favor hurricane development

– Global warming may impact - Out of phase relationship with Atlantic and

Pacific hurricanes - Wind shear

- El Niño/La Niña

Hurricane Destruction

- High winds

- Intense rainfall

- Storm surge – increase in shoreline sea level

Storm Destruction

- Historically destructive storms

– Galveston, TX, 1900

– Andrew, 1992

– Mitch, 1998

– Katrina, 2005

– Ike, 2008

– Irene, 2011

2005 Atlantic Hurricane Season

- Most active season on record

– 27 named storms

– 15 became hurricanes - Season extended into January 2006

- Five category 4 or 5 storms

– Dennis, Emily, Katrina, Rita, Wilma

Hurricane Katrina

- Costliest and deadliest U.S. hurricane

- Category 3 at landfall in Louisiana

– Largest hurricane of its strength to make landfall in U.S. history - Flooded New Orleans

Hurricanes Rita and Wilma

- Rita – September 2005

– Most intense Gulf of Mexico tropical cyclone

– Extensive damage in Texas and Louisiana - Wilma – October 2005

– Most intense hurricane ever in Atlantic basin

– Multiple landfalls

– Affected 11 countries

Historic Hurricane Destructions

- Most hurricanes in North Pacific

- Bangladesh regularly experiences hurricanes

– 1970 – massive destruction from storm - Southeast Asia affected often

- Hawaii

– Dot in 1959

– Iwa in 1982

Future Hurricane Threats

- Loss of life decreasing due to better forecasts and evacuation

- More property loss because of increased coastal habitation

Ocean’s Climate Patterns

- Open ocean’s climate regions are parallel to latitude lines.

- These regions may be modified by surface ocean currents.

Ocean’s Climate Zones

- Equatorial

– Rising air

– Weak winds

– Doldrums - Tropical

– North and south of equatorial zone

– Extend to Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn

– Strong winds, little precipitation, rough seas - Subtropical

– High pressure, descending air

– Weak winds, sluggish currents - Temperate

– Strong westerly winds

– Severe storms common - Subpolar

– Extensive precipitation

– Summer sea ice - Polar

– High pressure

– Sea ice most of the year

Sea Ice Formation

- Needle-like crystals become slush

- Slush becomes diskshaped pancake ice.

- Pancakes coalesce to form ice floes.

- Rate of formation depends on temperature.

- Self-perpetuating

- Calm waters allow pancake ice to form sea ice.

Iceberg Formation

- Icebergs break off of glaciers.

– Floating bodies of ice

– Different from sea ice - Arctic icebergs calve from western Greenland glaciers.

- Carried by currents

- Navigational hazards

Shelf Ice

- Antarctica – glaciers cover continent

– Edges break off

– Plate-like icebergs called shelf ice - Shelf ice carried north by currents

- Antarctic iceberg production increasing due to global warming.

Wind Power

- Uneven solar heating of Earth generates winds.

- Turbines harness wind energy.

- Offshore wind farms generate electricity.

Global Ocean Wind Energy

Reference: All images and content are taken from Essentials of Oceanography by Alan P. Trujillo and Harold V. Thurman, 12th Edition.