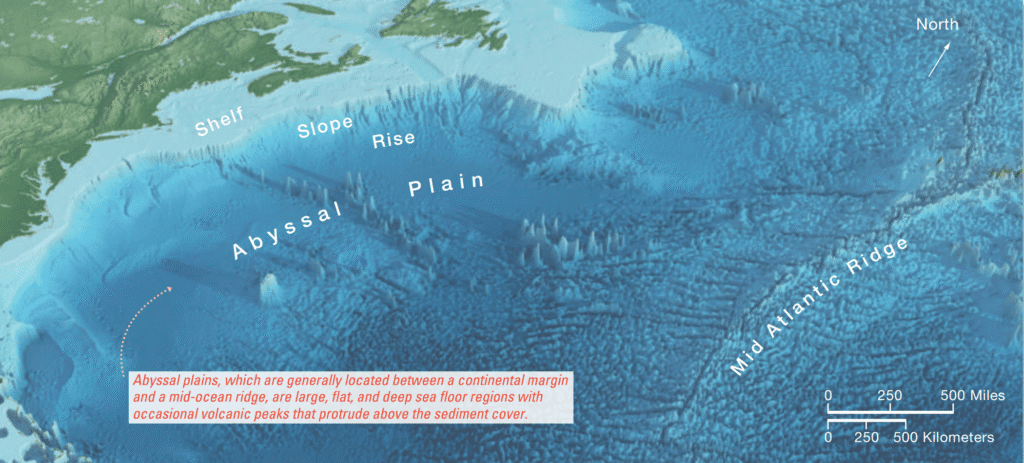

The deep-ocean region extends beyond the continental margin province—which comprises the shelf, slope, and rise—and encompasses a diverse range of notable geological features.

Abyssal Plains

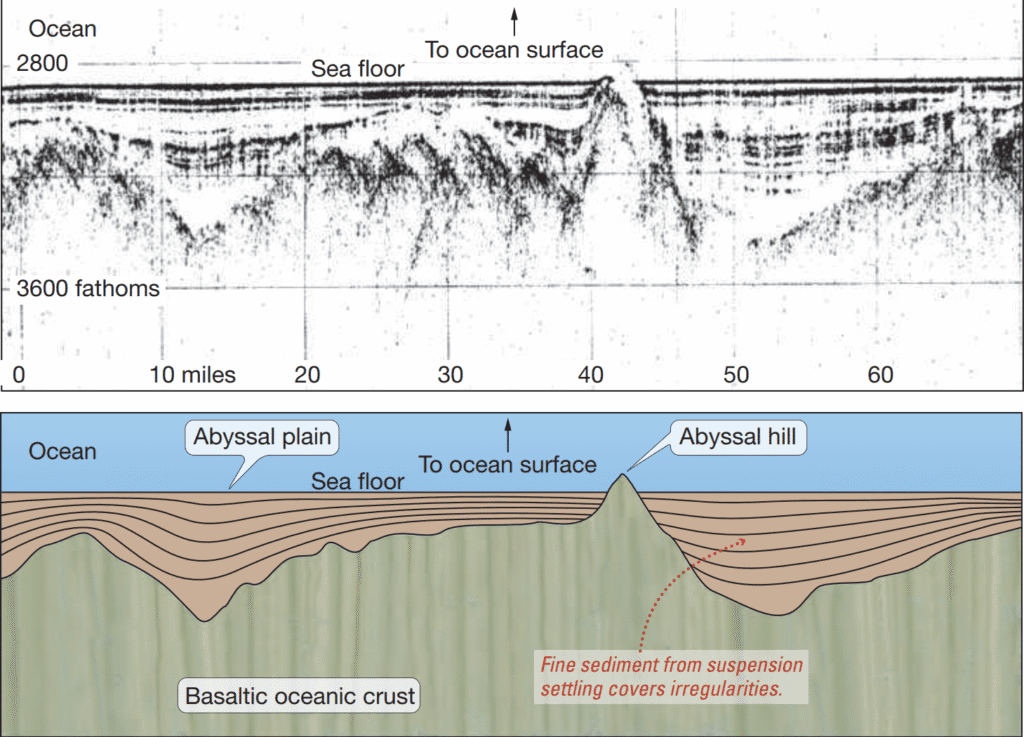

Stretching outward from the base of the continental rise into the expansive deep-ocean regions are extremely flat depositional surfaces characterized by inclinations of less than a degree. These regions, termed abyssal (from a = without and byssus = bottom) plains, span significant portions of the ocean floor and typically lie at depths between 4500 meters (15,000 feet) and 6000 meters (20,000 feet). Although not truly bottomless, they represent some of Earth’s deepest and most level terrains.

These abyssal plains are formed through the gradual accumulation of fine-grained sediments that settle onto the ocean floor over prolonged periods. This process, known as suspension settling, results in a thick sedimentary blanket composed of minuscule particles akin to “marine dust.” Over geological timescales, such sediment layers effectively mask most of the irregular topographical features of the deep-ocean seabed. Additionally, turbidity currents originating from terrestrial sources contribute further to the sedimentary buildup.

The presence and distribution of abyssal plains are directly influenced by the type of continental margin bordering the ocean basin. For example, the Pacific Ocean contains relatively few abyssal plains, whereas they are more prevalent in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. This discrepancy arises from the deep-ocean trenches along the convergent active margins of the Pacific Ocean, which function as sediment traps by halting the movement of particles beyond the continental slope. Essentially, these trenches serve as gutters, capturing sediments delivered from land via turbidity currents.

In contrast, along the passive margins of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, turbidity currents are able to travel uninterrupted down the continental margin, subsequently depositing sediments across the abyssal plains. Furthermore, the vast distance from the continental margin to the deep-ocean floor in the Pacific results in the premature settling of many suspended particles, thereby limiting their reach. Meanwhile, the comparatively smaller expanse of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans facilitates the unimpeded transport of sediment to their respective deep-ocean basins.

Volcanic Peaks of the Abyssal Plains

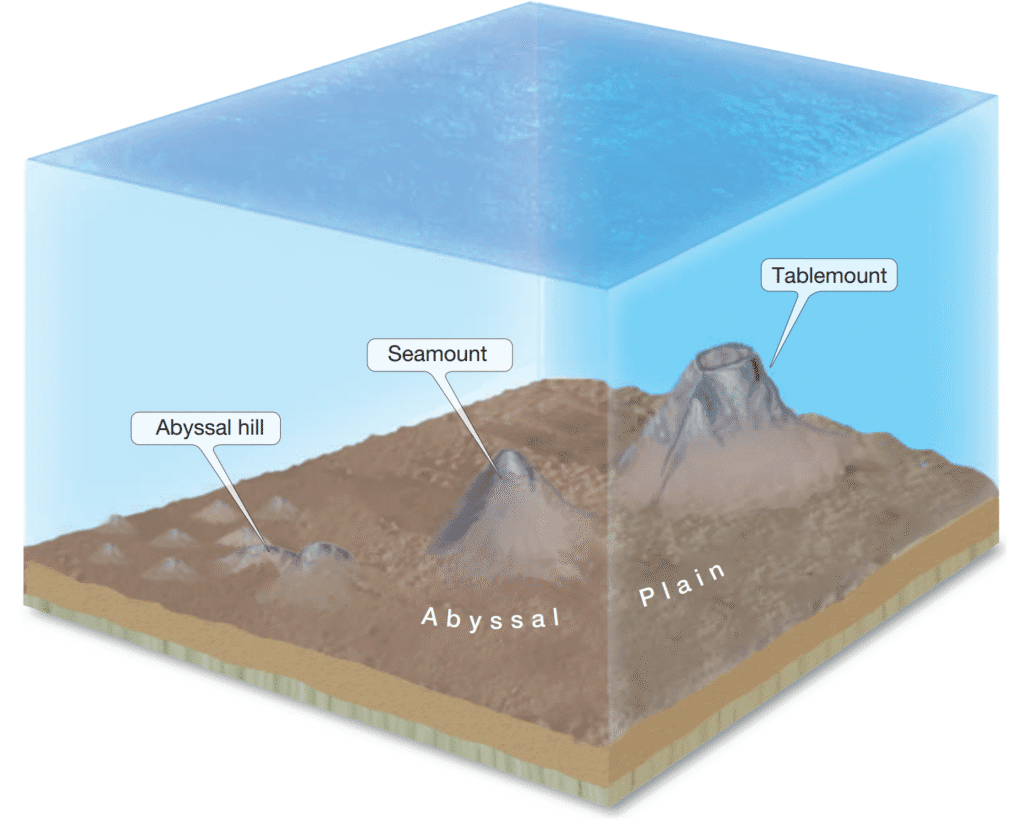

Protruding through the sedimentary cover of the abyssal plains are numerous volcanic peaks, each rising to various altitudes above the oceanic crust. Some emerge beyond sea level to form islands, whereas others remain just beneath the ocean surface. Those submerged features that ascend more than 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) above the deep-ocean floor and possess a pointed summit, resembling an inverted ice cream cone, are identified as seamounts. Globally, experts estimate the existence of over 125,000 recognized seamounts, many of which originate from volcanically active regions such as hotspots or along the mid-ocean ridge.

Alternatively, when a volcanic structure has a flat-topped summit, it is referred to as a tablemount or guyot. The formation processes of seamounts and tablemounts are elaborated in earlier chapters.

Volcanic formations on the seafloor that do not exceed 1000 meters (0.6 mile) in elevation—falling below the defined height of a seamount—are classified as abyssal hills or seaknolls. These features are among the most abundant geological structures on Earth, with several hundred thousand identified to date, spanning large portions of the ocean basin floor. They are typically gently rounded and exhibit an average height of approximately 200 meters (650 feet). The majority are created through crustal extension during the generation of new oceanic crust at the mid-ocean ridge. Notably, recent scientific findings reveal a strong correlation between the occurrence of ice ages and the formation of abyssal hills. During such periods, the lowering of sea levels results in diminished hydrostatic pressure over the mid-ocean ridge, which in turn allows the mantle to produce greater quantities of magma, thus increasing the formation rate of abyssal hills.

In the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, numerous abyssal hills are concealed beneath layers of abyssal plain sediment. However, in the Pacific Ocean, where the presence of deep trenches along the ocean margins effectively captures terrestrial sediments, the rate of sedimentation is substantially lower. This facilitates the development of extensive terrains dominated by abyssal hills, commonly termed abyssal hill provinces. Evidence of submarine volcanic activity in the Pacific Ocean is especially prominent. Indeed, over 20,000 volcanic peaks have been identified on the Pacific seafloor, including the recently discovered and largest known single volcano on Earth—Tamu Massif—which rivals the largest volcano in the solar system, Olympus Mons on Mars.

Ocean Trenches and Volcanic Arcs

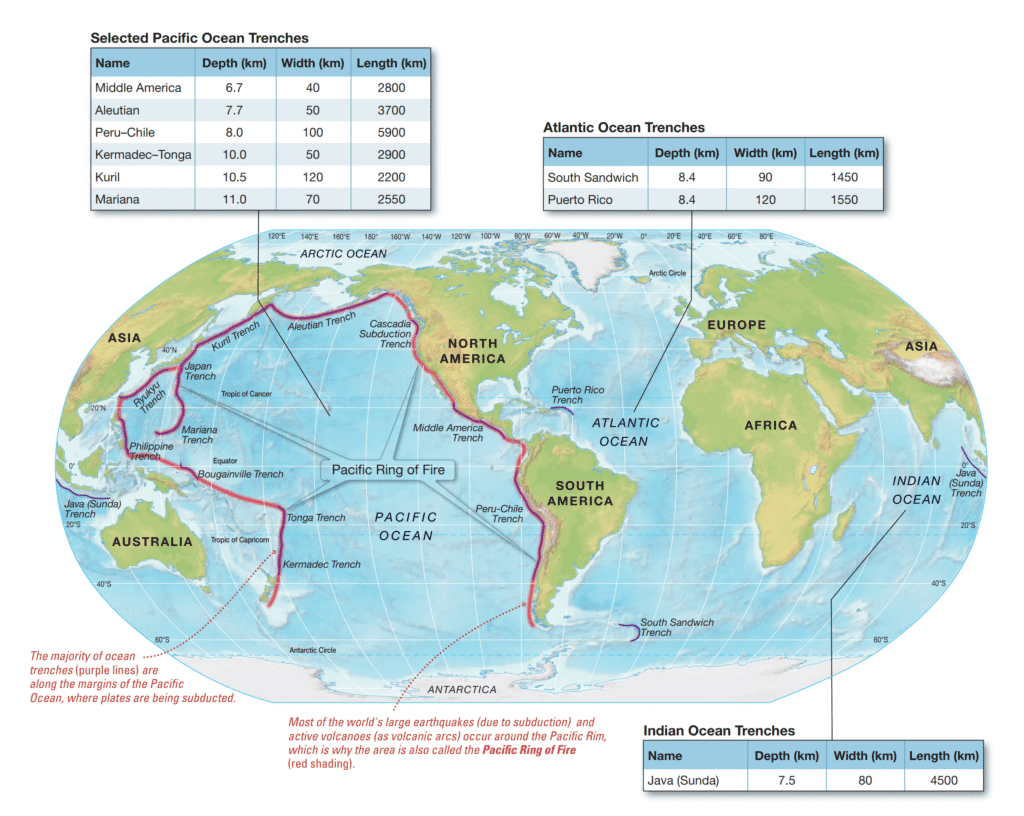

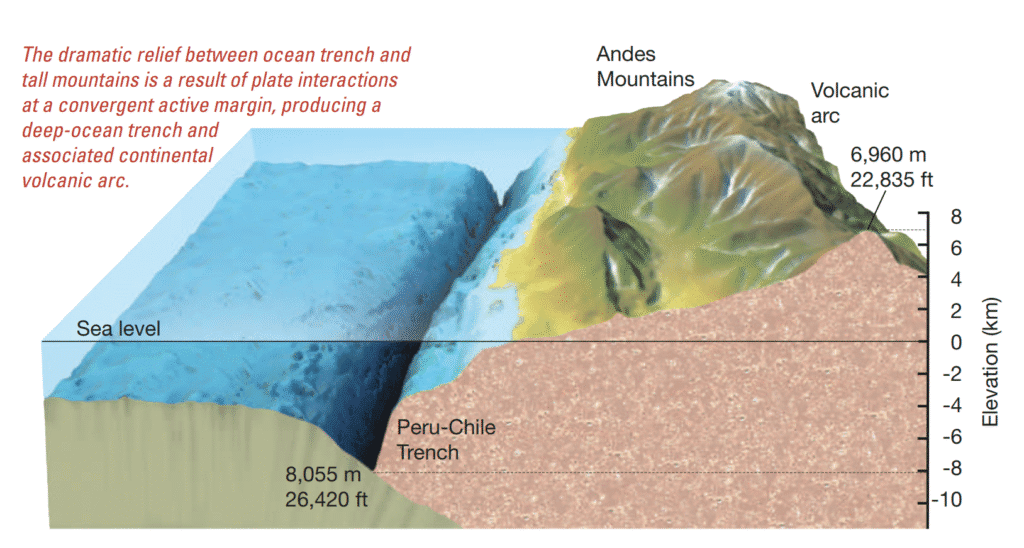

In regions characterized by passive margins, the continental rise typically forms at the base of the continental slope, gradually transitioning into the abyssal plain. By contrast, in convergent active margins, the slope leads into an elongated, narrow, and steep-sided ocean trench. These trenches represent deep, linear depressions carved into the seafloor as a result of tectonic plate collisions along convergent plate boundaries. On the side of the trench facing the landmass, a volcanic arc often emerges, forming either island chains—as seen in Japan, an island arc—or volcanic mountain ranges along continental edges—such as the Andes Mountains, a continental arc.

These trenches host the deepest known regions of the oceanic environment. In fact, the Challenger Deep segment of the Mariana Trench marks the lowest point on Earth’s surface, descending to a depth of 11,022 meters (36,161 feet). Most ocean trenches are located along the Pacific Ocean margins, whereas only a limited number exist within the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

The Pacific Ring of Fire

The Pacific Ring of Fire extends along the periphery of the Pacific Ocean and contains the majority of the world’s active volcanoes and major earthquake zones. This is attributed to the high concentration of convergent plate boundaries that encircle the Pacific Rim. One significant section of the Pacific Ring of Fire includes the western coast of South America, notably the Andes Mountains and the adjacent Peru–Chile Trench. A cross-sectional analysis of this region illustrates the dramatic vertical relief characteristic of convergent boundaries, where deep-ocean trenches coexist with towering volcanic arcs.

Reference: All images and content are taken from Essentials of Oceanography by Alan P. Trujillo and Harold V. Thurman, 12th Edition.