In the complex discipline of Earth Science, the ability to visualize terrain from a synoptic, bird’s-eye perspective has revolutionized our understanding of the planet’s crust. Photogeology—the systematic study and interpretation of geological features using aerial photographs—serves as the critical bridge between raw visual data and detailed geological maps. While the advent of satellite remote sensing and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has transformed the geologist’s toolkit, the fundamental principles of photogeologic interpretation remain indispensable for mineral exploration, engineering site selection, and environmental monitoring.

However, the transition from analog stereoscopy to digital photogrammetry brings unique challenges. This comprehensive guide provides a forensic analysis of the distinct advantages and limitations of photogeology. We explore how this classic technique integrates with modern technology to solve complex problems—from the mechanics of vertical exaggeration to the cost-benefit analysis of aerial versus field surveys—ensuring you understand both the capabilities and the constraints of aerial interpretation in the 21st century.

What is Photogeology? Defining the Scope of Aerial Interpretation

Photogeology is the science and practice of interpreting aerial and space-borne imagery to extract qualitative and quantitative geological information about the Earth’s surface and subsurface structures.

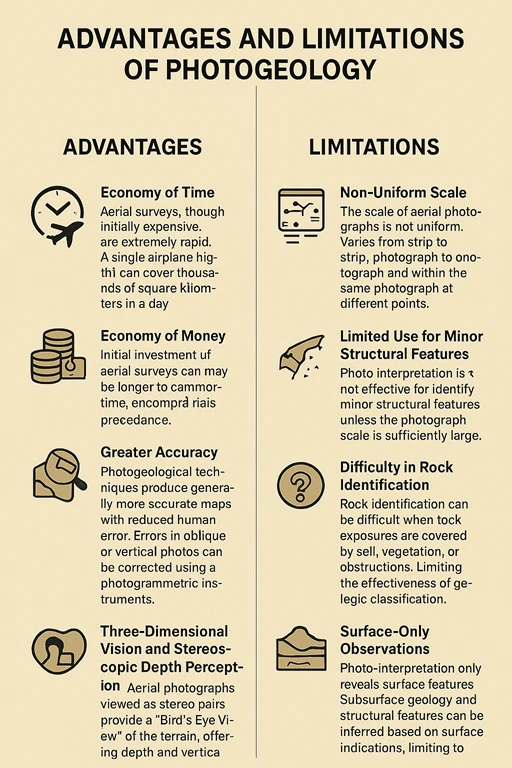

Photogeology offers significant advantages over conventional geological surveys. These include economy of time (covering thousands of square kilometers in a day), cost savings (75% reduction compared to fieldwork), greater accuracy through precise boundary mapping, and three-dimensional vision via stereoscopic depth perception.

However, it also has limitations, such as non-uniform scale, difficulty in identifying minor structural features, challenges in rock identification, and surface-only observations of geological formations.

The Mechanics and Utility of Vertical Exaggeration

One of the most distinct but often misunderstood characteristics of stereoscopic photogeology is vertical exaggeration. In the realm of stereoscopic viewing, the vertical scale of the 3D model often appears significantly larger than the horizontal scale—sometimes by a factor of 3 to 5 depending on the base-height ratio of the photography. While novice interpreters might view this as a distortive nuisance that complicates slope measurement, experienced photogeologists utilize this exaggeration as a critical analytical tool.

In geological terrains characterized by low relief, such as peneplains, eroded sedimentary basins, or shield areas, subtle geological features are often invisible to the naked eye on the ground. A dip slope of only 2 degrees or a faint fracture trace might be indistinguishable from the surrounding topography when viewed horizontally. However, vertical exaggeration effectively “stretches” the terrain, amplifying these micro-topographic variances. A gentle dip becomes a noticeable slope; a minor fault scarp becomes a distinct break in the terrain. This amplification allows for the mapping of structural lineaments, bedding attitudes, and subtle geomorphological boundaries that would otherwise be missed during a standard field walkover.

It is important to note, however, that this visual aid requires mental calibration. Interpreters must be aware that the steepness of slopes is artificially enhanced. Without this awareness, engineering assessments regarding slope stability or landslide risk could be grossly overestimated. Therefore, while vertical exaggeration is an invaluable advantage for detection, it imposes a limitation on direct measurement, requiring mathematical correction or the use of parallax bars to derive true dip angles.

Key Advantages of Aerial Photogeology in Geological Mapping and Structural Interpretation

Photogeology, or aerial photo-interpretation applied to geological work, offers several advantages over conventional geological fieldwork. While there are some disadvantages, the main advantages are as follows:

1. Economy of Time

Aerial surveys, though initially expensive, are extremely rapid. A single airplane flight can cover thousands of square kilometers in a day, whereas a ground survey would take years. For instance, during oil exploration in the Sahara desert, aerial photography became a key tool, allowing the construction of accurate geological maps necessary for prospecting. These maps sped up the work significantly, allowing oil companies to save both time and money. For example, in the Sahara desert, photogeological surveys resulted in a three-quarter reduction in time and money compared to manual fieldwork.

2. Economy of Money

While the initial investment in aerial surveys may be higher due to the cost of airplanes, cameras, and related equipment, in the long run, the overall expense is significantly lower than that of traditional fieldwork. Once the cost of equipment is covered, the multipurpose nature of aerial photographs makes this method more economical.

3. Greater Accuracy

Maps created using photogeological techniques are generally more accurate than those produced by conventional methods, as human error is reduced. Boundaries between geological formations, field objects, and cultural features are reproduced precisely in aerial photographs. Although errors can occur in oblique or vertical photographs due to relief displacement in areas with high relief, these errors can be easily corrected using photogrammetric instruments. Close cooperation between field geologists and photogeologists ensures better accuracy through field checks and the use of all available geological information during photo interpretation.

4. Three-Dimensional Vision and Stereoscopic Depth Perception

A unique advantage of photogeology is the ability to create three-dimensional models under a stereoscope. Aerial photographs viewed as stereo pairs provide a “Bird’s Eye View” of the terrain, offering a sense of depth and vertical exaggeration. This stereoscopic vision is especially useful for interpreting regional features such as folds, faults, unconformities, and geomorphic features like domes, basins, plains, and plateaus. A geologist can get a comprehensive view of the terrain before conducting fieldwork.

Limitations and Constraints of Aerial Photography in Geological Exploration and Hazard Assessment

Despite the many advantages of aerial photo interpretation, certain drawbacks and limitations must be considered. While these limitations can be mitigated, beginners in photogeology should be aware of the following issues:

1. Non-Uniform Scale

The scale of aerial photographs is not uniform. It can vary from strip to strip, photograph to photograph, and even within the same photograph at different points. This non-uniformity can complicate accurate interpretation across a wide area.

2. Limited Use for Minor Structural Features

Photo interpretation is not very effective for identifying minor structural features unless the scale of the photograph is sufficiently large. Small-scale geological structures such as minor folds, joints, lineation, foliation, current bedding, and ripple marks are often not captured in sufficient detail on standard aerial photographs.

3. Difficulty in Rock Identification

In some cases, accurately identifying rock types can be difficult, especially if the rock exposures are covered by surface materials such as soil, vegetation, or other obstructions. This limits the effectiveness of photo-interpretation for direct rock classification.

4. Surface-Only Observations

Photo-interpretation only reveals surface features. Subsurface geology and structural features can only be inferred based on physiographic and structural indications observed on the surface. While helpful, this limits the ability to fully understand the geology without additional techniques or tools.

Though these limitations hinder the effectiveness of photo interpretation, they can be addressed to a large extent by combining aerial surveys with periodic field checks. This integration allows for more accurate and reliable geological interpretations.

Integrating Photogeology with GIS and Remote Sensing Workflows

Modern photogeology has evolved far beyond the limits of the stereoscope and light table; it is now an integral component of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and multi-sensor remote sensing workflows. In the contemporary digital earth science environment, the “photogeological map” is rarely a final product but rather a foundational vector layer within a complex geospatial database.

The integration process typically begins with the orthorectification of aerial photographs to remove the radial distortions caused by the camera’s central projection and terrain relief. Once these images are geometrically corrected, they serve as a base map upon which photogeological interpretations (faults, lithological contacts, lineaments) are digitized. This vector data is then superimposed over other remote sensing datasets, such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) or multispectral satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel-2).

This data fusion is critical for overcoming the inherent limitations of optical photography. For instance, while aerial photos provide excellent textural data for identifying structural grains, they cannot penetrate dense vegetation. By integrating a LiDAR-derived “Bare Earth” model—which digitally strips away the vegetation canopy—geologists can correlate the lineaments visible in the aerial photos with the subtle topographic signatures revealed by the LiDAR. Furthermore, multispectral integration allows for the correlation of visual rock types with specific mineralogical spectral signatures (e.g., clay alteration zones or iron oxides). This synergistic approach, often referred to as “Smart Mapping,” significantly enhances the predictive accuracy of mineral exploration and hazard assessment models, making the combined output far more valuable than the sum of its parts.

Very good content