After the decline of the Mauryan Empire in 2nd century BC, small dynasties sprang up in various parts of India. Among them, Shungas, Kanvas, Kushanas and Shakas in the North and Satvahanas, Ikshavakus, Abhiras and Vakatakas in Southern and Western India gained prominence. Similarly, the religious scene saw the emergence of Brahmanical sects such as the Shaivites, Vaishnavites and Shaktites. The art of this period started reflecting the changing socio-political scenario as well. The architecture in the form of rock-cut caves and stupas continued, with each dynasty introducing some unique features of their own. Similarly, different schools of sculpture emerged and the art of sculpture reached its climax in the post-Mauryan period.

Architecture

Rock-cut Caves

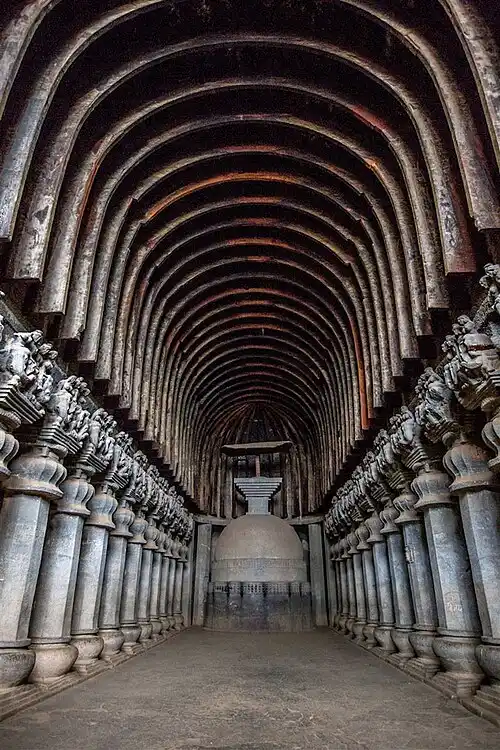

The construction of rock caves continued as in the Mauryan period. However, this period saw the development of two types of rock caves – Chaitya and Vihar. While the Vihars were residential halls for the Buddhist and Jain monks and were developed during the time of the Mauryan Empire, the Chaitya halls were developed during this time. They were mainly quadrangular chambers with flat roofs and used as prayer halls. The caves also had open courtyards and stone screen walls to shield from rain. They were also decorated with human and animal figures.

Examples: Karle Chaitya Hall, Ajanta Caves (29 caves – 25 Vihars + 4 Chaitya), etc.

Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, Odisha

They were made under the Kalinga King Kharavela in 1st-2nd century BC near modern-day Bhubaneswar. The cave complex has both artificial and natural caves. They were possibly carved out as residence of Jain monks. There are 18 caves in Udayagiri and 15 in Khandagiri.

Udayagiri caves are famous for the Hathigumpha inscription which is carved out in Brahmi script. The inscription starts out with “Jain Namokar Mantra” and highlights various military campaigns undertaken by the King Kharavela. Ranigumpha cave in Udayagiri is double-storied and has some beautiful sculptures.

Stupas

Stupas became larger and more decorative in the post-Mauryan period. Stone was increasingly used in place of wood and brick. The Shunga dynasty introduced the idea of torans as beautifully decorated gateways to the stupas. The torans were intricately carved with figures and patterns and were evidence of Hellenistic influence.

Examples: Bharhut Stupa in Madhya Pradesh, the toran at Sanchi Stupa in Madhya Pradesh, etc.

Sculpture

Three prominent schools of sculpture developed in this period at three different regions of India – centred at Gandhara, Mathura and Amaravati.

Gandhara School

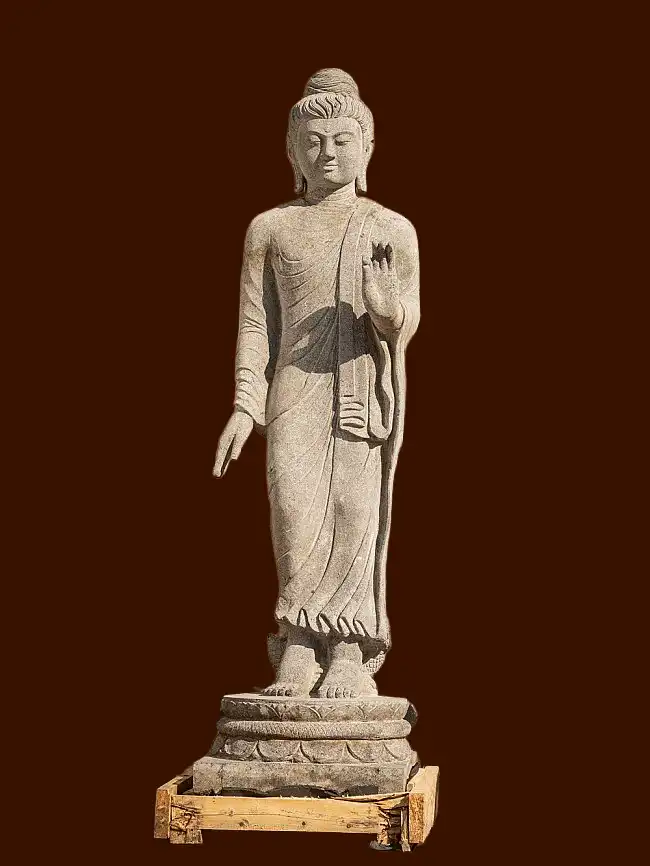

The Gandhara School of Art developed in the western frontiers of Punjab, near modern day Peshawar and Afghanistan. The Greek invaders brought with them the traditions of the Greek and Roman sculptors, which influenced the local traditions of the region. Thus, Gandhara School also came to be known as Greco-Indian School of Art.

The Gandhara School flourished in two stages in the period from 50 BC to 500 AD. While the former school was known for its use of bluish-grey sandstone, the later school used mud and stucco for making the sculptures. The images of Buddha and Bodhisattvas were based on the Greco-Roman pantheon and resembled that of Apollo.

Mathura School

The Mathura School flourished on the banks of the river Yamuna in the period between 1st and 3rd centuries AD. The sculptures of the Mathura School were influenced by the stories and imageries of all three religions of the time – Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. The images were modelled on the earlier yaksha images found during the Mauryan period.

The Mathura School showed a striking use of symbolism in the images. The Hindu Gods were represented using their avayudhas. For example, Shiva is shown through linga and mukhalinga. Similarly, the halo around the head of Buddha is larger than in Gandhara School and decorated with geometrical patterns. Buddha is shown to be surrounded by two Bodhisattavas – Padmapani holding a lotus and Vajrapani holding a thunderbolt.

Amaravati School

In the Southern parts of India, the Amaravati School developed on the banks of Krishna river, under the patronage of the Satvahana rulers. While the other two schools focused on single images, Amaravati School put more emphasis on the use of dynamic images or narrative art. The sculptures of this school made excessive use of the Tribhanga posture, i.e. the body with three bends.

Differences Between Gandhara, Mathura and Amaravati Schools

| Basis | Gandhara School | Mathura School | Amaravati School |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Influence | Heavy influence of Greek or Hellenistic sculpture, so it is also known as Indo-Greek art. | It was developed indigenously and not influenced by external cultures. | It was developed indigenously and not influenced by external cultures. |

| Ingredient Used | Early Gandhara School used bluish-grey sandstone while the later period saw the use of mud and stucco. | The sculptures of Mathura School were made using spotted red sandstone. | The sculptures of Amaravati School were made using white marbles. |

| Religious Influence | Mainly Buddhist imagery, influenced by the Greco-Roman pantheon. | Influence of all three religions of the time, i.e. Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. | Mainly Buddhist influence. |

| Patronage | Patronised by Kushana rulers. | Patronised by Kushana rulers. | Patronised by Satvahana rulers. |

| Area of Development | Developed in the North West Frontier, in the modern day area of Kandahar. | Developed in and around Mathura, Sonkh and Kankalitila. Kankalitila was famous for Jain sculptures. | Developed in the Krishna-Godavari lower valley, in and around Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda. |

| Features of Buddha Sculpture | The Buddha is shown in a spiritual state, with wavy hair. He wears fewer ornaments and seated in a yogi position. The eyes are half-closed as in meditation. A protuberance is shown on the head signifying the omniscience of Buddha. | Buddha is shown in delighted mood with a smiling face. The body symbolises mascularity, wearing tight dress. The face and head are shaven. Buddha is seated in padmasana with different mudras and his face reflects grace. A similar protuberance is shown on the head. | Since the sculptures are generally part of a narrative art, there is less emphasis on the individual features of Buddha. The sculptures generally depict life stories of Buddha and the Jataka tales, i.e., previous lives of Buddha in both human and animal form. |

|  |  |

Greek Art and Roman Art

Greek and Roman styles have some difference, and Gandhara School integrates both the styles. The idealistic style of Greeks is reflected in the muscular depictions of Gods and other men showing strength and beauty. Lots of Greek mythological figures from the Greek Parthenon have been sculpted using marble. On the other hand, Romans used art for ornamentation and decoration and is realistic in nature as opposed to Greek idealism. The Roman art projects realism and depicts real people and major historical events. The Romans used concrete in their sculptures. They were also famous for their mural paintings.

VARIOUS MUDRAS RELATED TO BUDDHA

1. Bhumisparsha Mudra

One of the most common Mudras found in statues of Buddha.

It depicts the Buddha sitting in meditation with his left hand, palm upright, in his lap, and his right hand touching the earth.

This mudra is commonly associated with blue Buddha known as Akshobya.

Significance: ‘Calling the Earth to Witness the Truth’ and it represents the moment of Buddha attaining enlightenment.

2. Dhyana Mudra

Indicates Meditation and is also called ‘Samadhi’ or ‘Yoga’ Mudra.

It depicts Buddha with both hands in the lap, back of the right hand resting on the palm of the left hand with fingers extended. In many statues, the thumbs of both hands are shown touching at the tips, thus forming a mystic triangle.

It signifies attainment of spiritual perfection.

This Mudra was used by Buddha during the final meditation under the bodhi tree.

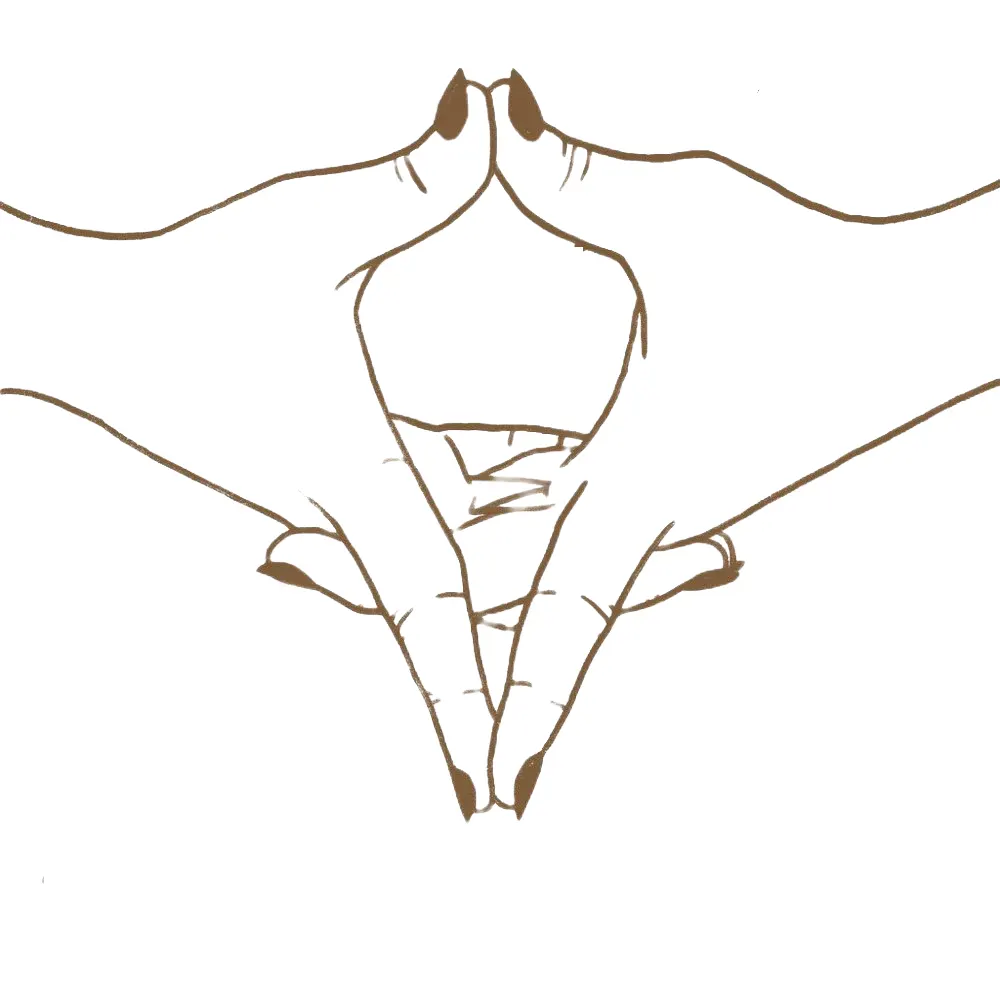

3. Vitarka Mudra

It indicates teaching and discussion or intellectual debate.

The tips of the thumb and index finger touch each other, forming a circle. The right hand is positioned at shoulder level and the left hand at the hip level, in the lap, with palm facing upwards.

It signifies the teaching phase of preaching in Buddhism. The circle formed by the thumb and index finger maintains the constant flow of energy, as there is no beginning or end, only perfection.

4. Abhaya Mudra

It indicates fearlessness and symbolises strength and inner security.

The right hand is raised to shoulder height with arm bent. The palm of the right hand faces outwards and the fingers are upright and joined. The left hand hangs downwards by the side of the body.

This gesture was shown by Buddha immediately after attaining enlightenment.

5. Dharmachakra Mudra

It means ‘Turning the Wheel of the Dharma or Law’, i.e. setting into motion the wheel of Dharma.

This Mudra involves both hands.

The right hand is held at chest level with the palm facing outwards. A mystic circle is formed by joining the tips of the index finger and the thumb. The left hand is turned inward and the index finger and thumb of this hand join to touch the right hand’s circle.

This gesture was exhibited by Lord Buddha while he preached the first sermon to a companion after his enlightenment in the Deer Park of Sarnath.

6. Anjali Mudra

This mudra signifies greetings, devotion, and adoration.

Both hands close to the chest, palms and fingers join against each other vertically.

It is common gesture used in India to greet people (Namaste). It signifies adoration of the superior and is considered a sign of regards with deep respect.

It is believed that true Buddhas (those who are enlightened) do not make this hand gesture and this gesture should not be shown in Buddha statues. This is for Bodhisattvas (who aim and prepare to attain perfect knowledge).

7. Uttarabodhi Mudra

It means supreme enlightenment.

Holding both hands at the level of the chest, intertwining all the fingers except index fingers, extending index fingers straight up and touching each other.

This Mudra is known for charging one with energy. It symbolises perfection.

Shakyamuni Buddha (liberator of Nagas) presents this Mudra.

8. Varada Mudra

It indicates charity, compassion or granting wishes.

The right arm is extended in a natural position all the way down, with the palm of the open hand facing outwards towards onlookers. If standing, the arm is held slightly extended to the front. Can be a left-hand gesture as well.

Through the five extended fingers, this Mudra signifies five perfections: Generosity, Morality, Patience, Effort and Meditative Concentration.

9. Karana Mudra

It indicates warding off evil.

Hand is stretched out, either horizontally or vertically, with the palm forward. The thumb presses the folded two middle fingers but the index and little fingers are raised straight upwards.

It signifies expelling demons and negative energy. The energy created by this mudra helps remove obstacles such as sickness or negative thoughts.

10. Vajra Mudra

It indicates knowledge.

This mudra is better known in Korea and Japan.

In this mudra, the erect forefinger of the left hand is held in the fist of the right hand. It is seen in the mirror-inverted form also.

This mudra signifies the importance of knowledge or supreme wisdom. Knowledge is represented by the forefinger and the fist of the right hand protects it.