Introduction

The Harappan or Indus valley civilization gave way to Vedic culture. The Vedic civilization is regarded as a major cultural achievement. “Vedic texts” are a good place to start if you want to learn more about Vedic culture or sources that contributed to the reconstruction of Vedic culture. The Indo-Aryans are the authors or composers of these writings. People who speak a subset of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family are known as Indo-Aryans.

The Indo-Gangetic lowlands were home to a large number of Indo-Aryans. They were nature worshippers who performed rituals like sacrifices. One of the most important sacrifice practice, for example, was Yajnas. While performing sacrifices, they would sing Richa/shloka.

All of these shlokas, as well as numerous forms of sacrifices, were together referred to as “Vedas”. Veda is a Sanskrit word that signifies “knowledge”. As a result, the Vedas are collections of all Aryan activities rather than distinct religious literature. Vedic literature evolved over many years and was passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth.

As a result, ‘Vedic Culture’ refers to the culture that gave birth to the Vedas. The ‘Early Vedic Period’ (Saptasindhu region) and the ‘Later Vedic Period’ (more internal/ interior section of India) are two stages of growth in Vedic civilization.

Indo-Aryans

There are differing perspectives on the Aryans’ origins. Numerous scientists and historians have proposed various views concerning the Aryans’ ancestral homeland.

One of the theories is given by Max Muller, German scholar of comparative language. The theory that he has proposed is known as “Central Asian Theory”. He claims that the Aryans originally lived in Central Asia and came to India as migrants whereas the European theory claims the Aryans inhabited Europe and voyaged to various places and the Aryans who came to India were an offshoot of the Europeans. The Indian theory claims Aryans were the residents of the Sapt Sindhu (the region stretching from the river Indus, reaching up to Saraswati river).

The most accepted view is that there was a series of Aryan immigration, and they came to the subcontinent as immigrants. The Rig Veda’s composers referred to themselves as Arya, which can be interpreted as a cultural or ethnic term. The word literally means kinsman or companion, or it may be etymologically derived from ‘ar’ (to cultivate).

According to Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Aryans originally inhabited Siberia, but due to the falling temperature, they had to leave Siberia for greener pastures.

Tibet Theory of Swami Dayanand Saraswati states Tibet is the original home of Aryans with reference to the Vedas and other Aryan texts.

Indian Theory of Aryan origin was supported by Dr. Sampurnanand and A.C. Das.

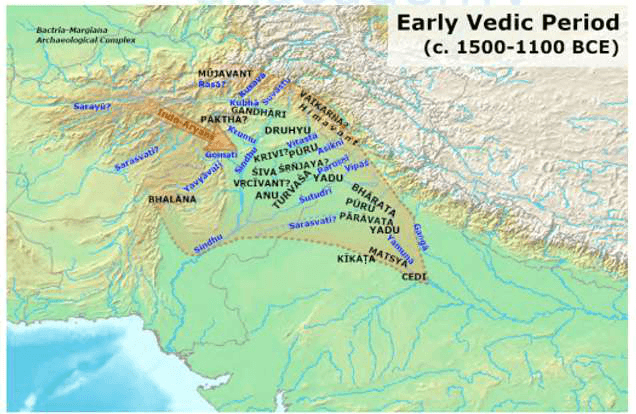

Geographical Area Known to Vedic Aryans

The various references found in Rigvedic Samhita helped in understanding the geographical area occupied by early Vedic Aryan and their geographical knowledge of Indian subcontinent.

After entering India, the Aryans got settled in the Sapta Sindhu region that is the land of seven streams.

These seven streams were river Indus and its five tributaries (Ravi, Beas, Jhelum, Chenab, Sutlej) and river Saraswati. These references suggest that Aryans got settled in Punjab and northern Rajasthan region.

As per the Hindu religious text Manusmriti described the Bramhavarta, as land between Saraswati and Drishadwati, which is also known as Ghaggar.

Rigvedic Aryans were aware of the Himalayas because they used to procure soma plant from Mujavant peak of the Himalayas.

The word “Samudra” occurs 133 times in Rigveda. Its literal meaning is any mass of water. Some scholars are this view that the people of the Rigvedic culture were not aware of the sea but mostly scholars pay attention that there were many references in Rigveda which indicates that the Rig Vedic people had direct knowledge of the sea. At the same time, Rig-Veda also speaks about the western and eastern Samudra.

River Saraswati is mentioned the maximum number of times (72 times). This indicates that Saraswati was the most significant river in the life of Rigvedic Aryans.

The references found in Later Vedic literature revealed that Aryans had moved upto central Bihar, and they were aware of Geography of almost the whole of India.

Literary Sources to Understand Vedic Age

The four Vedas composed during this period are the Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda. The Samhitas, Aranyakas, Brahmanas, and Upanishads are the four subdivisions of each Veda. The Vedic corpus is divided into two categories by historians: From the beginning to the conclusion, Vedic texts: The Rig Veda Samhita’s family books are considered early Vedic literature. The Rig Veda Samhita, as well as the Samhitas of the Sama, Yajur, and Atharva Vedas, as well as the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads linked with all four Vedas, make up later Vedic literature.

Vedic literature not only consists of the four Vedas but also of Dharma sutra, Puranas, Epics etc.

Vedic Literature in Early Vedic Period

The Rig Veda, India’s oldest Veda, tells the story of the early Vedic people of India. There are a total of ten Mandalas, two to nine of which date back to the Vedic period. UNESCO has included the Rig Veda to its list of World Human Heritage Literature.

Natural powers such as fire, rain, wind, dawn, and sun are honoured in the ‘Richas,’ or prayers. Such skills are possessed by Varuna, Indra, Agni, Surya, Marut, Usha, and others.

Some Gods are beneficent (“want good things for others”), while others are malignant (“desire bad things for others”) (they wish evil on others).

The Vedic Literature can also be split into the following categories:

- Shruti Literature: Shruti refers to the most-revered body of sacred literature, considered to be the product of divine revelation. These are works that are thought to have been heard and passed down by worldly sages. Shruti literature includes the four Vedas as well as their Brahmanas.

- Smriti Literature: Smriti is a Sanskrit word that means ‘recollection.’ These texts were solely relied on memory; as a result, these texts are about demonstrating the Vedic culture’s tradition. It is the one that is remembered by the general public. Epics, Puranas, Manu laws, tantric treatises, and Kautilya’s Arthasastra are all instances of Smritis.

Vedic Literature in Later Vedic Period Rig- Veda (1st and 10th Mandalas)

- Mandala 1 is primarily dedicated to Indra and Agni. The gods Varuna, Surya, Mitra, Rudra, and Vishnu have all been named.

- In Mandala 10, Nadi Stuti Sukta celebrates the rivers. Purush Sukta and Nasadiya Sukta are also included.

- Hymns that are customarily sung at weddings and funerals are included.

- Early references to Vedic society’s divisions, such as Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras are found.

Yajur-Veda

- The purpose of this text is to explain how sacrifices were performed. However, at the time of offerings, the Rig Veda’s hymns were recited.

- As a result, the Rig-Veda is the source of the majority of the Yajur Veda’s hymns.

- It features rites that can be done either publicly or privately.

Sama-Veda

- The Sama Veda, often known as the “Veda of Chants,” is a compilation of poetry.

- The hymns of Sam-Veda are based on the Rig Veda and include musical notations to aid in the performance of devotional tunes.

Atharva-Veda

- It has a lot of spells and charms in it. This is the fourth and last chapter of the Veda. It deals with a wide range of topics, such as mysticism, sorcery and dark magic, betrayal, and so on.

Appendices of Vedas (Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads)

The Vedic Aryans created a new body of prose writing to convey Vedic knowledge. As a result, each Veda’s Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads were unique.

The Brahmanas contain information about Vedic song meanings, applications, and sources.

Each Veda is associated with a number of Brahmanas.

The Vedas pose philosophical and spiritualistic issues, such as one’s own being, the origin of the universe, and one’s soul relationships with God, which the Aranyakas and Upanishads address. The link between Brahmana and Upanishad is thought to be Aranyaka. It placed a greater focus on meditation than on sacrifices. They were primarily composed for students by hermits living in the woods. The Upanishads are primarily philosophical in nature and address the highest levels of knowledge.

- There are 108 Upanishads in total, with 13 being the most important.

- The National Emblem’s Satyamev Jayate is derived from the Mundaka Upanishad. Vedic explanation books (Vedangas, Shada-darshanas).

Vedangas

The Vedangas were designed to aid in the understanding of the Vedas in a more systematic and organised manner. It covered topics such as Shiksha (proper prayer pronunciation), Kalpa (appropriate sacrifice behaviour), Vyakaran (grammar), Nirukta (etymology of Vedic terms), Chhanda (musical recitation norms), and Jyotish (astrology) (proper time to perform sacrifices).

The Shad-darshanas

The Shad-darshanas were created to help people understand the philosophical content of the Vedas, such as Sankhya (of Kapil, explaining the unity of soul with God), Nyaya (of Gautam, explaining logic), Yog (of Patanjali), Vaisheshika (of Kanand, regarding atoms), Purva-mimasa (Jaimini, Vedic rituals), Uttar-mimasa (Badarayana, structure of the universe, spiritualism).

Early Vedic period (circa 1500-1200 BC)

Political Life of Rig Vedic Aryans

The “Rig Vedic Samhita” is the most important early Vedic source.

The early Rig Vedic society was a pastoral economy, semi-nomadic tribal culture. The tribal chief was known as Rajan, Gopati, or Gopa, and the tribe was known as Jana (protector of cows).

The political system was one of equality.

The liberal and progressive political and administrative structure were in place.

There was no concept of state.

The political organisation of the society was similar to that of a monarchy, but the Gopati’s position was not hereditary, and he was chosen from among the clan’s men.

Bureaucracy was in a nascent stage.

Judicial system was in a very early stage.

War and battles were frequent. Democratic elements were present- popular assemblies. There are several tribes within the Vedic Tribe:

Some of the important functionaries of Rig Vedic Societies were –

- Purohit (priest)

- Senani (leader of an army)

- Gramini (leader of a village)

Some of the important tribal assemblies of this period were –

- Sabha -> Smaller body meant for elites (exclusive body)

- Samiti -> Broad-based folk assembly, presided over by the Rajan

- Vidatha -> Tribal assembly with diverse functions

- Gana -> Assembly or troop

The main unit of political organisation was the Kula, or family led by Kulapa. It covered anyone who shared a residence (Griha). A grama, or village, is made up of multiple households, similar to what we see now, and its headman was known as Gramini. ‘Vis’ was the name given to a group of numerous ‘Grama’ (head-Vishpati). That is to say, the Vis were the entire tribe’s people. The ‘Jana’ was a group of such ‘Vis’ led by Gopa or Gopati. The ‘Rashtra’ was the larger form (Raja). Rashtra, led by Rajan, was created by a group of Jana.

Emergence of King

Many tribes or ‘janas’ were constantly at war with one another, and these wars were mainly fought over the issue of the ‘cattle-theft’ and ‘defend against cattle-theft,’ collectively known as ‘Gavishti.’

Although they were at constant war against each other, these tribes never had a standing army. But such wars were carried out by the tribal warriors themselves. Their wars were for the cattle thieves and not for lands.

Some point of time, warriors of the tribes formed matrimonial alliances and became familiar with one another. Because of the this a particular class of the warriors were emerged within the Vedic tribes, and they were called as ‘Rajanya’.

These ongoing wars or fights necessitated the selection of a valiant and heroic leader to lead the warriors on the battlefield. This requirement for a combat leader led to the establishment of a ‘king,’ which resulted in the formation of the ‘Sabha,’ (or people’s assembly), which decided and chose a monarch.

- The king was tasked with fighting wars or defending the tribe against external invasions.

- In exchange, citizens pledged to send him gifts (Bali) on their own initiative. The king had to swear that he would rule in accordance with canon law. He was probably in charge of guarding his tribe as well as taking as much cattle as he could from rival tribes. The king, on the other hand, could not exercise his power at pleasure. The restraints he faced included Sabha and Samiti (for his selection), People/ Vish (for gifts or payment), Rajanyas/ lineage of warriors (since he was chosen from among them), and Mantri (because he was chosen from among them) (advised king).

According to A.L. Basham, the monarch’s popular authority was limited by his responsibility to the Sabha and the Samiti.

He was also reliant on his tribe’s religious elite, since priests used to coronate him and bestow divine legitimacy on his reign.

It’s worth noting that the title of ‘Rajan’ was first given to someone in the Rig Vedic era, but it gradually became hereditary.

Administration

The Sabha, Samiti, and Ministry assisted and managed the king’s administrative structure.

Sabha and Samiti

- The Visha (or people) used to convene in their Grams at a specific spot in order to dominate it.

- The conference was called ‘Sabha’.

- On a regular basis, samiti meetings were held, and administrative matters were openly discussed.

- The ‘Samiti’ was a gathering of tribe members (Visha). People used to gather there to discuss a wide range of issues and problems, as well as to play, eat, and drink.

- On the other side, the ‘Sabha’ was made up of a limited group of persons who dealt with sensitive problems. Executive decisions include whether to go to war or engage in a treaty, creating weights-and-measures regulations, assisting the king in judicial problems, and so on.

- The king was elected by Sabha and the Samiti, so both these assemblies had power to oversee the functions of the king. Apart from Sabha and Samitis there were other 2 assemblies which were known as Vidhata, to discuss for war booty distribution and Gana, (was the Highest Advisory Body).

- As time passed, the term ‘Sabha’ acquired different shades of the meaning. The “Apastambha Sutra” describes being used as a meeting hall. In other instances, Sabha is referred as a “body of men singing together”. Hence the term Sabha denotes both the assembly (During the early Rig-Vedic period) and the assembly hall (in later Rig-Vedic period).

Ministry

- King had various minister for smoot and effective governance. This council of minster was made up of:

- He was the king’s most trusted advisor, the Purohit (priest). He was responsible for giving the king political and religious guidance. He was also the one who bestowed religious legitimacy to the king. As a result, he played a significant role.

- He was in charge of the troops, Senapati (commander). He was tasked with defending, fighting wars, and establishing military camps, among other things.

- The spies’ mission was to ensure that information flowed freely. Duta (spy): The spies were under his command. He was in charge of international relations as a ‘duta.’

- Due to the king’s limited power region, the Gramini (village-headman) were also appointed to the king’s government.

- These ministers were intended to advise and approve the king’s decisions. In this sense, the people of that time and political set-up was based on responsible government with the involvement of grassroot people in ensuring transparency with a focus on protecting their interests.

Judiciary

- The King used to settle court disputes with the help of his ministry and Samiti. The law is based on Vedic writings, practises, and elders’ knowledge.

- Robbery, banditry, forgery, cattle-lifting, and indebtedness are just a few of the offences that could result in a death sentence.

Economy

- According to passages in the Rigvedic Samhita, the early Vedic economy was pastoral. It had a cattle-based herding economy.

- A person’s wealth was determined by the number of cows he owned.

- The government (and its salary) were funded entirely by voluntary donations from the Vish/people. In the nascent stage, Bali is mentioned. But there was no mechanism to collect it.

- Raids were yet another source of revenue.

Agriculture

- 4th mandala of Rigveda contains a reference to agriculture. But this reference is considered to be a later edition.

- It is believed that Rigvedic Aryans did not practice agriculture as the principal occupation.

- Shifting agriculture was performed, with fire being used to burn away forest cover and yava or barley being sown on the cleared land.

- Indra is also known as Urvarajit (winner of fruitful fields) in the Vedic pantheon, and there are references to Kshetrapati (guardian deity of agricultural fields)

- They didn’t have access to iron technology, but they were well-versed in copper. There were very few references to metallurgical activities.

- Land ownership by individuals was not yet a well-established concept.

- Wheat and barley were the predominant crops, with rice and paddy still in their early stages of growth.

- Farming, on the other hand, was strictly for survival at the time.

- Simple agricultural skills such as fertiliser application, sickle crop cutting, and water source arrangement were all familiar to the Vedic Aryans.

Pastoralism

- The people of the Early Vedic era lived in a pastoral culture. Raising animals was done for a variety of reasons, including wool, milk, agriculture, leather, and drawing chariots. The Aryan diet consisted primarily of milk products. Cattle were the main source of wealth in their civilization. As a result, the family was dubbed the “Gotras” (literally means cattle pen). Bhardwaj Gotra was one of the names given to the families based on the name of the cow pen where they lived.

Cattle returning from pastures was regarded to be a good omen. As a result, the ‘Goraja Muhurta’ ceremonies were held.

Cattle-lifting or cattle-lifting defence were the main reasons for the battles. As a result, ‘Gavishti’ became the name meaning war.

To distinguish cattle, their ears were chopped in a specific way. They possessed exclusive pasture property that they shared with the rest of the town.

Secondary economic activities

- A number of arts and crafts flourished during this age.

- Carpentry, Leather working, Weaving, spinning, gold smithing, silver smithing, Bronze smithing were important crafts.

- Among them, carpentry was the most respected profession because carpenters used to manufacture chariot.

Trade

- the Rigvedic Aryans were involved in trade and business to some extent. The majority of trade is done on the basis of barter.

- The economy was not monetized.

- The niskha, which was made of gold, was the money unit.

- The most common type of property was a cow.

- People relied heavily on war spoils as a source of revenue.

- There was no concept of land ownership.

- The resources belonged to the clan as a whole.

- The taxation system was still in its infancy.

- Bullock carts and pack bulls, as well as watercraft, were used.

- Those who worked in the trades were known as ‘Pani.’

- Clothes and leathers were the most commonly traded products.

- Although cattle were the primary means of exchange, there is mention of nascent currencies such as Nishka. Fishing was a part of the adventure as well.

Education

- The classes, which were held at the professors’ residences, were paid for by the monarchs.

- Both boys and girls were welcome to participate. Students were taught both vocational and moral principles in such Gurukulas. The information was not written down, but rather passed down orally down the centuries.

Society

- Because Vedic Aryans lived in a tiny tribal community, early Vedic social life was tribal in nature. The tribal values, norms, customs practices decided social relations and behaviour.

- The society was liberal, progressive, and egalitarian in nature.

- Varna was the term for colour. The indigenous people conquered by Aryans were called Dasas and Dasyus. Differentiation based on occupation existed. The untouchability believed to have been first mentioned in “Dharmasutra” Elements of purity and pollution, such as the practice of untouchability were absent in the Vedic period.

- The clan and kinship ties were important in society.

- Life revolved around primary relations.

- Cotton, wool, and animal hide were used to make Vedic clothing. The clothing was referred to as ‘Nivi,’ ‘Vasam,’ ‘Adhirasam,’ ‘Drapi,’ and so on.

- The higher degree of openness in social set-up was one of the main features of the open society at the time of the Vedic period.

- The family was the smallest unit or primary unit of society.

- The tradition of a joint family was followed because the members of a number of generations used to live together.

- The Vedic family was patriarchal, with the eldest person (Grihapati/kulapa) serving as the family’s head. He used to represent members of the family in socio-cultural matters.

- The family was part of a larger grouping, called vis or clan. A clan is a group of people who have united together due to a kinship relationship. They are also known as sub tribal groups. One or more than one clan made jana or tribe. The jana was the largest social unit.

Culture

- Since they first practised pastoralism, milk and meat have been part of the Vedic diet. They ate barley, oilseeds, vegetables, wheat, and fruits, among other things.

- Traditional non-vegetarian feasts were served at weddings, gatherings, and marriages. They even consumed intoxicating drinks on a regular basis, despite the fact that consuming such intoxicants was strictly forbidden in Vedic literature. Animal races and battles were popular among the Vedic people. Hunting was also a recreational activity, and they enjoyed listening to music while doing so. For entertainment, a variety of musical instruments, including string instruments and percussion instruments, were utilized, all of which were constructed of animal leather. In the Vedic literature, the subject is mentioned. They also had a good time doing a group dance. Both men and women participated in common-dance during the festival season, and gambling was a popular hobby. In general, women and men preferred different ornamental styles.

Marriage

- Marriage was also practised throughout the Early Vedic period.

- There were no child marriages.

- Marriages between varnas were common.

- Monogamy was the rule, but polygamy was also practised. Polygamy was much more common, but polyandry was exceptional.

- Dowry was not present.

Status of women

- Women had a high social status. The women enjoyed status almost equal to their male counterparts. Women had enjoyed a respectable position within the family as well as in society. Sabha and Samiti meetings were attended by women. This suggests that women had political power.

- Some professions, like spinning and weaving, were only available to women.

- Without the participation of the wife, some rituals and ceremonies were deemed incomplete.

- The place of the mother in the family was highly reputed.

- The females received education along with their male counterparts. Some of the women remained students throughout their life; they were known as Brahmavadinis.

Ghosha, Apala, Vishvavara, Lopamudra, Sikata, Navavari, Godha, Aditi, and other Vedic women who remained unmarried for higher education or learning enjoyed tremendous respect and distinction in society.

- Some of the women like Apala, Ghosha, Lopamudra and Vishwawara had attained such a high level of learning that they composed hymns of Rigveda.

- Women were only allowed to conduct two sorts of sacrifices: Sita Yajnya and Rudrabali Yajnya. These sacrifices were made, among other things, so that women may have healthy crops and children, marry, and aid their husbands in winning wars.

- There was a highly developed system of oral learning during the Early Vedic Age script was not known.

- Gurukulas were established by sages to bring education to the masses.

- Women’s marriages took place only when they had attained adulthood.

- Their approval is also important in their marital decision.

- Adult marriages, marriage-at-will, and widow remarriages were all permitted in early Vedic culture.

Religion

- Nature worship was the most important feature of the religious system of the Early Vedic Period. Various natural forces and phenomena were considered divine. They were given the names of gods and goddesses.

- Naturalistic polytheism (akin to primordial animism) is reflected in the Rig Veda, where natural forces such as wind, rain, water, thunder, and so on are believed to be an essential aspect of their religious rites. Yajnas were commonly used to worship in the open air.

- Except for the cow, which was regarded as aghnya in Vedic writings, flesh-eating and sacrificial killing of animals are mentioned in Vedic texts (not to be killed).

- The predominance of male deities was another important feature, but the place of the female goddesses was secondary.

- Rituals and sacrifices were dedicated to specific gods and goddesses.

- Henotheism was practised where different deities were accorded the highest significance on different occasions by Vedic Aryans.

The main Gods of early Rig-Vedic people were as follows:

- Indra was worshipped as a god of war. Cattle were prized by the Vedic people since they were pastoralists. As a result, cattle assaults and defence were common throughout this time period. Naturally, ‘warts-on cattle’ was a matter of concern, and Indra rose to prominence among the Gods as a result. Indra is the character who appears in most passages.

- Varuna: According to Vedic thinking, the entire universe operates according to a set of laws known as ‘Rita.’ Varuna was considered to be the ‘Rita’s owner.’ As a result, the Vedic people adored Varuna.

- Food is believed to reach the Gods through the ‘Yajnya (fire).’ As a result, Vedic people used to perform yajnas to honour the Gods. Yajna was an integral element of Vedic people’s religious ceremonies and rituals on a daily/occasional basis. Domestic and societal activities were judged complete without the success of yajna. As a result, the Vedic people revered Agni (fire) as a link between humanity and God. The “Earth’s Sun Mirror” is what it’s been dubbed. The prayers and sacrifices were not made to achieve eternal happiness or to satiate intellectual desires. It was carried out with the goal of getting necessary financial advantages from powerful and uncontrollable persons.

- Surya (Sun) is revered by the Vedic people.

- The ‘Usha’ is the subject of several poems in the Rig-Veda.

- Prithvi (Earth): Prithvi was revered as the creator of all living things.

- Yama is the Death God. He was revered not for his favour but to get away from him.

- Rudra is the God of the storm. In the same way that Yama was worshipped to prevent his wrath, he was worshipped to avoid his wrath as well.

- The rituals and sacrifices were simple.

- The role of the priest class was not very important in religion during the Early Vedic age.

- Animal worships were also prevalent.

- The Vedic Aryans considered the cow as a sacred animal.

- Religious activities were characterised by the predominance of a materialistic outlook.

- Rituals and sacrifices were performed to get sons, cattle, wealth, and victory in battles.

- The philosophical dimensions of religion were in a very early stage.

- The Rigvedic Aryans had no clear concept of heaven and hell.

During the later Vedic period (approximately 1200-600 BC)

- The Aryans migrated to more internal lands/interior portions of India. As a result, they ruled over vast areas of land with near-total authority. They came across a variety of villages, tribes, and governmental systems during their travels.

Polity

- During this time, the concept of territory and territorial governance began to take shape. Mahajan padas, for example, were formed by combining lesser kingdoms.

- Warfare was beginning to be fought on a large basis, and nature was getting more deadly by the day. As a result, in light of the current situation, the king’s requirement became incredibly crucial. A new type of governing structure was developed, in which the priests were given power. Varna system was established, which was based on the birth, to maintain the status quo and complete hold on power, the King/ruling class and the priests. Under this arrangement, the descendants of the ruling class and the priestly class were inevitably made kings or priests.

The king’s power was multiplied. Rituals and sacrifices such as Rajasuya (consecration ceremony), Vajpeya (chariot race), and Asvamedha (horse sacrifice) were made to elevate the king’s prestige Because the priests who performed the sacrifices benefitted financially from huge gifts, they elevated the monarch to divine status, and the king was thus identified with the Gods. As a result, the concept of ‘Divine Kingship’ was formed. The ruler and his bloodline came to prominence in Vedic society.

The Vaishyas were compelled to remain Vaishyas while paying the king’s taxes.

- Children of Vaishyas were automatically made Vaishyas and were required to pay taxes.

- Shudras’ children, on the other hand, are Shudras from birth.

- As a result, the system consolidated power in two classes (ruling and priestly) while also providing a steady source of tax revenue and physical labour.

Administrative setup

- The personalities of Sabha and Samiti shifted. They were ruled by chiefs and wealthy nobles. Women were no longer permitted to take part. As the King’s power grew, the importance of Sabha and Samiti decreased.

- In the government, the king was aided by counsellors. The original ministries were kept, but new ministers were appointed. Mahishi (King’s Main Queen), Purohit (Priest), Senani (Commander), Sangrahit (Treasurer—to monitor the kingdom’s income and expenditure), Bhagdut (Tax Collector), Gramini (Village Headman), and Suta (Chariot driver) were all appointed to the council of ministers.

- Gods’ Kingship: The King is now solely responsible to the Gods. He didn’t have to listen to whatever the ministry had to say. It was not required to adhere to the suggestions. As a result, the old ‘Mantris’ regulation is no longer in effect. He was now in a position to compel the Vish to give him gifts. As a result, rather than being a choice act, the donations became a ‘tax’.

- Because of the frequency of battles, King was forced to systemize his military system. As a result, a proper military structure arose throughout this time period. Rules were developed, as well as a hierarchy. Running away from the war was considered a source of disgrace and shame, but dying on the battlefield was seen as honourable. Women, children, and the defenceless were thought to be immoral targets.

Economy of Later Vedic age

- The transition from the Later Vedic to the Early Vedic periods is marked by the development of agriculture.

- Agriculture became the Later Vedic people’s primary source of income.

- Around 1000 B.C., the Vedic Aryans were the first to practise agriculture on a large scale.

- In the Satapatha Brahmana, ploughing ceremonies are given their own chapter.

- Foodgrains such as wheat, barley, and rice were now farmed.

- The plough was used to cultivate the land.

- One of the main activities of the Later Vedic people was mixed farming (cultivation and herding).

- During the Later Vedic period, knowledge of iron and metallurgy resulted in the birth of a variety of new crops.

- There was also industrial work such as metals, ceramics, and carpentry.

- At this point, Vedic Aryans began to produce a large surplus.

- The flourishing of crafts and trade was aided by the expansion of agricultural surplus.

Trade

- Trade and commerce had also expanded during this period.

- As agricultural commodities grew increasingly plentiful, trading progressed.

- The Vedic Aryans now ruled over a far broader territory than before. Markets have spread as a result of this.

- The discovery of items such as Lapis Lazuli (Found in Afghanistan) from later Vedic cities such as Bagwanpura indicates that the Later Vedic Aryans traded far off the land during this age.

- The monetisation of the economy was still absent. The barter system was followed. Sometimes Nishka and satamana were used as a medium of exchange. These were ornaments, not coins. The cow was still the main form of property. The concept of property in the form of the land was yet to emerge.

The significance of war booty as a source of income got reduced because Vedic Aryans had started producing their own food.

As trade developed, merchants were driven to band together.

- As a result, proto-guilds or early trading organisations arose.

- Foreign trade with distant regions like Babylon and Sumeria was made.

Because a specific type of pottery (painted grey ware) was utilized during that period, the Later Vedic culture is also known as the Painted Grey Ware–Iron Phase culture.

Society

- The tribal character of society got diminished.

- Society was not such liberal, progressive and egalitarian when compared with the Early Vedic age.

- The social mobility and openness in society had also got reduced marginally.

- The clan and kinship ties were still very important.

- The family was like the Early Vedic age.

- Marriage was like the Early Vedic age.

- Society is divided into four Varnas. As four different varnas, Brahmanas (priests), Kshatriyas (rulers), Vaishyas (agriculturists, traders, and artisans), and Shudras (slaves) (servers of the upper three classes) were created. The expanding worship of sacrifices bolstered the Brahmanas’ power. The Vedic jurist felt compelled to tie society together by enforcing a set of rigid rules and regulations. To do so, they established a variety of social institutions, such as the Ashram system, Varna system, Marriage system, Samskara system, and so on.

- Dharma, Artha, Kama, and Moksha, according to Purushartha, are the four major obligations of a man’s life.

- The following is the Ashrama concept: In this system, a person’s life is divided into four parts, and he is assigned labour based on his age.

- Brahmacharya: A person’s formative years. It is spent in celibacy, under the guidance of a Guru, in supervised, sober, and pure contemplation in order to prepare the mind for spiritual insight.

- Grihastha: This is the stage of a householder’s married and professional life when he or she marries and pleases Kama and Artha.

- Vanaprastha is the gradual disengagement from the physical world. Giving your children greater responsibilities, devoting more time to religious traditions, and going on holy pilgrimages are all good ideas.

- Sanyasa: During this period of penance, one gives up all worldly possessions.

Jurists devised the Samskaras idea to impose socio-religious punishments at any stage of a person’s physical and psychological growth, as well as the need for social interaction. Such Samskara followed every aspect of his life, from conception to death.

- The first reference to class separation can be found in the 10th Mandala, in the Purusha Sukta of the Rig-Veda. Various responsibilities were allocated to each Varna under this system, like as

- A Brahman is someone who studies, instructs, performs, and hosts sacrifices. As a result, they were the sole source of religious authority during this time period. In order to obtain religious legitimacy for their rule, the rulers made huge contributions to the Brahmans.

- Education, performing sacrifices (Yajna), and protecting people and territory were all important to the Kshatriya. Most of the rulers and warlords/warriors in this Varna were rulers and warlords/ warriors. With the help of Brahmans, the Kshatriyas were able to legalise their status, allowing them to centralise power in their hands. Varna was a political force to be reckoned with in its own right.

- Vaishya is an agriculturist and a dealer. This Varna was home to farmers, merchants, and artisans. They were a powerful Varna in Vedic civilization due to their economic strength. They were members of society who paid taxes. Despite their economic might, traders and artisans were never given higher respect in the Vedic religious system. As a result, they were interested in non-Vedic religions such as Buddhism and Jainism in later centuries.

- The Shudras are in charge of looking after the other three Varnas. They were at the bottom of the social ladder in Varna, with no advantages or rights in the community. They had limited influence over the processes of production. Some historians believe that the people who lived in this Varna were native to the area.

- Varna status of a person begins to be linked with the profession as well as birth. The degree of social mobility got reduced.

- The functions of various varnas were defined elaborately for the first time. This description is found in Aitareya Brahmana.

- Varna membership was established by birth in the later Vedic period when the Varna System became hereditary. This system was built with a lack of mobility and flexibility in mind. As a result, Varna has been renamed Jati (birth group), or Caste. During this period, sacrifices were more essential, and as a result, the Brahmans, who controlled religion, increased in social status.

- Vaishya, or tax collectors, agriculturists, and merchants increased in power. The three are known as Travarnikas, or men of higher Varnas (Brahmans, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas).

- On the other hand, the Shudras remained poor and were forced to work for the traivarnikas. As a result of the idea of untouchability, a class of untouchables arose alongside these four Varnas.

Dietary Habits

- Dietary practices from the early Vedic era persisted into the later Vedic period as well, but the later Vedic period witnessed a higher consumption of non-vegetarian food. Vedic sacrifices were carried out on a large scale during this time, and it became an extremely time-consuming procedure. During such times, a large number of animals were sacrificed.

Marriage

A person enters Grihasthashram after completing Brahmacharya Ashrama. During this time, a person’s normal expectation was to marry. We know that by marrying and having children, one can be released from his parents’ ‘rina (debt=responsibility)’.

The Vedic people followed a patriarchal family arrangement, similar to that of the early Vedic period.’ Inter-Varna weddings were frowned upon at the time, and same gotra/family marriages’ were forbidden.

In order to maintain the patriarchal structure, jurists, on the other side, deny marriages at will.

Types of Marriages

- Brahma-Vivaha: In accordance with ancient rituals and customs, the father lends his daughter’s hand to the knowledgeable and well-behaved bridegroom.

- Daiva-Vivaha, the priest performing the sacrifice, receives the bride’s hand from her father.

- Prajapatya-Vivaha: The bridegroom’s father greets him and encourages the pair to carry out their religious duties.

- Arsha-Vivaha: Father gives the bride’s hand after receiving a pair of cattle from the Groom.

- Gandharva-Vivaha: Only the husband and bride’s agreement is required for marriage at will.

- Asur-Vivaha: When a groom gives the bride’s father and family money to buy her for marriage, it is referred to as Asur-Vivaha.

- Rakshasa-Vivaha is a marriage based on kidnapping. It entails the kidnapping of a woman and forcing her to marry.

- Paishacha-Vivah: By making the female unconscious and breaching her chastity.

- The first four types were the only ones that were used.

Religion

- Indra and Agni had lost their importance. The gods Vishnu (preserver) and Prajapati (creator) rose to prominence. Shiva appeared during this time.

- Sacrifices and ceremonies became more complex, costly, and time-consuming. Sacrifices were given priority over prayers. Prayers became less significant as celebrations became more elaborate. The people were informed that if they followed the sacrificial laws, the Gods would have no choice but to reward the sacrificers. Ceremonies like Rajasuya, Vajapaya, and Ashwamedha sacrifice used to continue for months and years together. It established the authority of the chiefs over the people. It reinforced the territorial aspect of the polity since people from all over the kingdom were invited to these sacrifices. Huge expenditure was incurred during these sacrifices.

- Along with magic, superstitions and blind faith were a part of religious life.

- During the Later Vedic period, the priestly class grew in importance due to the complexities of rites and sacrifices. Brahmana emerged as the most important category among all the priests. Buddhism and Jainism evolved towards the end of this period as a result of this orthodoxy.

- The priest class amassed a large quantity of money in the form of dana and Dakshina.

- Indra and Agni, the two most significant Rig Vedic Gods, lost their power, and Prajapati (the Creator) took their place.

- Idolatry first appears in the Later Vedic period.

- Pushan (who was intended to look after animals) became too known as the Shudras’ god.

- Ancient Vedic worshippers offered sacrifices to the gods in the hopes of receiving material rewards in exchange. People worshipped gods for the same material reasons they did in former periods during this time period. On the other hand, the way people worshipped changed tremendously.

- Improving the next life and securing heaven was some of the prominent objectives behind rituals and ceremonies.

The philosophical dimension of religion emerged in a developed form.

- The idea of heaven and hell, salvation and transmigration of the soul is found in detail in the Upanishads.

Entertainment

- In the later Vedic period, the sorts of amusement and the means by which they were offered varied. At the time, several events were utilized to organise themselves, which were similar to the early Vedic period.

- During this period, strong kings ruled and long feasts were conducted.

- Races, hunting, and gambling became a part of every gathering of people.

Position of Women in Later Vedic Period

- During this time, women were treated as second-class citizens and lived in deplorable conditions. Their situation worsened. Women were not permitted to attend Sabhas or Samitis, which were public assemblies.

- These new constraints on women were sanctified by religion.

- Child marriages were becoming more common. Her right to education was taken away from her when she was married at a young age. Women were also required to be absolutely chaste because they were now accountable for the family’s honour (Izzat). As a result, her social mobility was limited, and women were confined to their homes. She had no choice but to stay at home and work as a housewife.

- Remarrying was forbidden, leaving her to live as a widow until her death.

- The birth of a daughter begins to be considered a curse.

- Participation of women in meetings of sabha and Samiti was no longer.

Role of Iron in the Life of Vedic Aryans

- The Vedic Aryans became aware of iron metallurgy around 1000 BC

- The knowledge of iron was of great significance because it was the strongest metal known to human beings at that time.

- The evidence of the knowledge of iron metallurgy has been revealed by archaeological excavations.

- Literary references are also found in later Vedic literature, where iron is mentioned as “ Shyama ayas” (Copper- Krishna ayas).

- Gradually, the use of iron tools and implements increased, as a result of which significant changes were witnessed in various dimensions of human life.

Role of Iron in Agriculture

- Historians have put forward different views about the extent of use of iron implements in agriculture and the impact of the knowledge of iron metallurgy on the progress of agriculture.

- Historians who studied the early Vedic period emphasized that knowledge of iron metallurgy was responsible for exceptional advancement in the later Vedic period.

- Professor R.S Sharma claims that iron ploughshares and iron axes were widely employed for forest clearing.

- According to this view, the use of ploughshare had helped in deeper ploughing, which was necessary for sugarcane and wet paddy cultivation. These crops had increased agriculture productivity quite significantly, and by 1000 B.C., the state of an agricultural surplus was attained.

- During archaeological excavation, only one iron ploughshare was discovered (zakira- U.P).

- According to Professor R.S Sharma, the iron ploughshare would have got decomposed in the hot, humid climate of the Gangetic region. He also emphasized that most of the excavations had been carried out in urban areas of the ancient ages. The rural settlements of the Vedic age have not been properly excavated. He also emphasized that the references found in satapatha Brahmana ploughshare being pulled by multiple bullocks or bulls were definitely related to iron ploughshare because these ploughshares pulled by multiple bullocks would not be made of wood.

- The latest research carried out about the extent of the use of iron implements in agriculture by historians like Nihar Ranjan Roy, and D.K Chakravarty has revealed that the role of iron was insignificant in agricultural activities during the Later Vedic age.

- Most of the iron objects discovered during excavations are in the form of weapons only.

- According to these researches, the Later Vedic Aryans used ploughshare made of hardwood. Hardwood trees like ebony were found in Gangetic valley during the Vedic age.

- The alluvial soil in Gangetic valley is quite soft.

- Forests were cleared by fire, according to passages found in the Satapatha Brahmana and Mahabharat. According to Mahabharat, khandava vana was cleared using fire.

- The attainment of the state of agriculture surplus in the 6th century BC was the outcome of the adoption of Indigenous agriculture know-how by Vedic Aryans.

- People of Koldihwa were practising wet paddy (Mirzapur, UP) civilization for ages.

- Once Vedic colonies moved into eastern India, this indigenous knowledge was adopted by them, which over the period of time resulted in the attainment of the state of agricultural surplus.

FAQs

What is Vedic era age?

The Vedic era spans two main periods: the Early Vedic Period (circa 1500-1200 BC) and the Later Vedic Period (approximately 1200-600 BC).

What are the main features of the Vedic period?

The main features of the Vedic period, encompassing both Early and Later phases, include:

Early Vedic Period: A pastoral economy and semi-nomadic tribal culture.

An egalitarian, liberal, and progressive society with no concept of a formal state.

Nature worship, simple rituals, and the practice of henotheism.

High social status for women, with participation in assemblies and no child marriages.

Oral learning as the primary mode of education.

Trade primarily based on barter, with no monetized economy or concept of individual land ownership.

Later Vedic Period: A significant shift to agriculture as the primary source of income, aided by the knowledge of iron metallurgy, leading to agricultural surplus.

The emergence of a more complex political structure with the concept of territory and divine kingship.

A rigid Varna system based on birth, leading to reduced social mobility and the emergence of untouchability.

Sacrifices and ceremonies becoming more complex, costly, and time-consuming, increasing the importance of the priestly class.

A decline in the status of women, with restricted participation in public assemblies and the rise of child marriages.

The first appearance of idolatry.