Niccolò Machiavelli The Prince and His Idea of Statecraft

Introduction: a world of city‑states and scheming princes

Florence at the turn of the sixteenth century was not a unified nation‑state but a patchwork of Italian city‑states jostling for supremacy. Republics, duchies and papal territories changed hands through intrigue and force. In the midst of this turmoil, a middle‑class diplomat named Niccolò Machiavelli observed politics from the inside. He served in the chancery of the Florentine Republic and negotiated with popes, kings and mercenary commanders. When the Medici family retook Florence in 1512 and dismissed him, Machiavelli found himself exiled to his farm outside the city. It was there, in 1513, that he wrote Il Principe (The Prince)—a slim treatise on how a ruler could seize and hold power.

Though short, The Prince was radical. Instead of preaching morality, Machiavelli told rulers to do what was necessary to preserve the state. His advice earned him a reputation as a cynic, even the father of political immorality. Yet his underlying aim was stability: he wanted to see Italy unified and strong in the face of French and Spanish interventions. To understand his idea of statecraft is to enter a world in which fortune is fickle, virtue is practical rather than ethical, and political survival depends on hard choices.

Machiavelli’s context and motivations

A republican loses his post

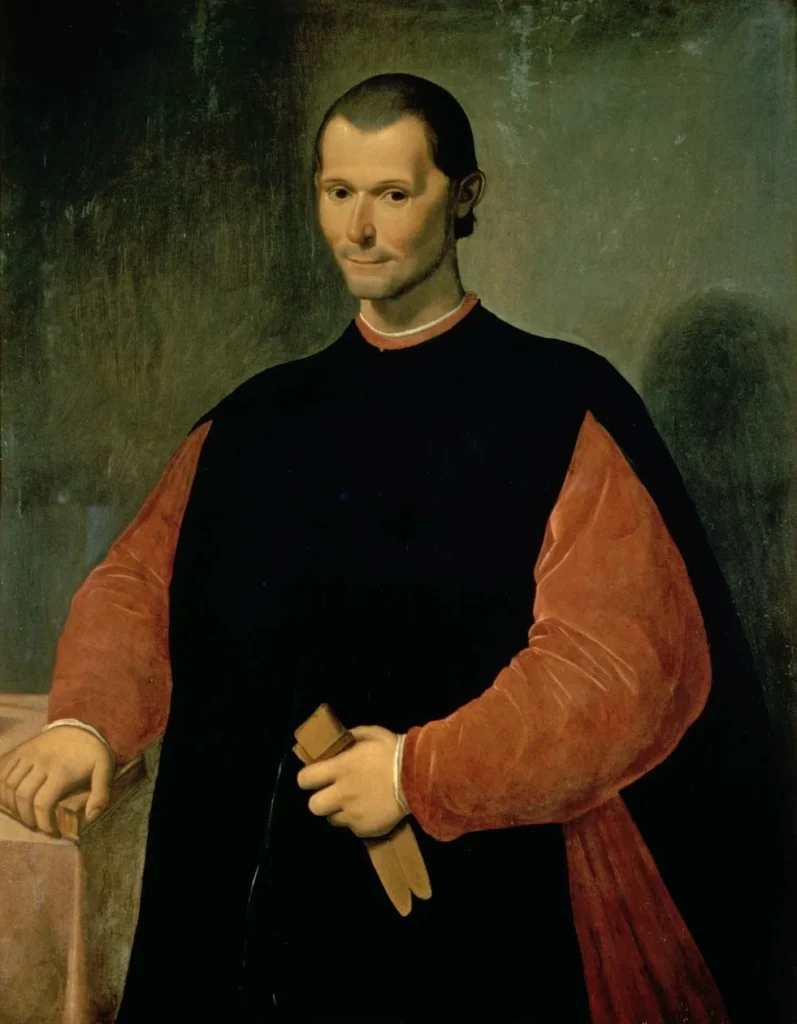

Machiavelli (1469‑1527) was born in Florence to a respectable but not wealthy family. Educated in the classics, he entered public life in 1498 as second chancellor of the Florentine Republic. In this role he travelled widely, meeting Cesare Borgia, Louis XII of France and the Holy Roman Emperor. His dispatches show a keen eye for human nature, military organisation and diplomacy.

When the Medici family—previously exiled bankers—returned to power in 1512 with Spanish support, they dismantled the republic and purged its officials. Machiavelli was dismissed, briefly imprisoned and then banished to his small estate at Sant’Andrea in Percussina. Eager to regain favour, he composed a treatise dedicated to Lorenzo de’ Medici. The Prince reads as a job application disguised as a manual. It also shows how a republican mind can reason pragmatically about princely rule, as if to say: “If I cannot serve a republic, I will tell princes how to govern effectively.”

A humanist turns to realpolitik

Renaissance thinkers usually tied good government to Christian or classical virtues. Machiavelli broke with that tradition. He wrote that past examples are essential for learning but that times change, and a ruler must adapt tactics to circumstances. He admired ancient Rome and the citizen armies of early republics but also praised contemporary figures like Cesare Borgia for their decisiveness. In the Discourses on Livy, his commentary on Roman history, he argues for a mixed constitution balancing popular and aristocratic elements. In The Prince, he focuses on single‑ruler principalities because Italy’s immediate problem was not the niceties of republican theory but the need to resist foreign invasion.

Statecraft: securing and maintaining the state

The state as a means, not an end

To Machiavelli, the state (lo stato) was not a moral community or a divine right; it was a public order. Its purpose was to protect its citizens and maintain security. If a ruler failed to preserve the state, high ideals were meaningless. This pragmatic view led him to separate public ethics from private morality. In private life one should be honest and merciful; in public life a prince may need to deceive, coerce or even commit cruelty if that is what necessity demands.

Machiavelli did not advocate cruelty for its own sake. He advises a prince to use violence quickly and decisively and then to refrain from further brutality. Excessive cruelty breeds hatred; moderate cruelty used to secure order can make later mercy possible. This notion—that the state sometimes must do unpleasant things for a greater public good—is the core of his idea of statecraft. Modern leaders might call it reason of state or realism.

Virtù and fortuna

Two concepts underpin Machiavellian statecraft: virtù and fortuna.

- Virtù does not mean virtue in a moral sense; it means strength, skill, courage and the ability to shape events. A prince with virtù is decisive, flexible, strategic and willing to act boldly. He reads the character of his times and uses opportunities swiftly.

- Fortuna is fortune or luck—the unpredictable forces of history and chance. Machiavelli depicts fortune as a woman who favours the bold. He famously writes that it is better to be impetuous than cautious, because fortune is like a torrential river that, when unprepared, devastates everything, but when prepared, can be channelled by dams and barriers. A wise ruler builds institutions and alliances to weather fortune’s floods.

The relationship between virtù and fortuna is dialectical. No one can control fortune entirely, but those with virtù can mitigate its effects by preparation and by seizing fleeting chances. This tension forms the heart of The Prince: how much can human agency overcome luck?

What is Virtù in Machiavelli’s Philosophy

Machiavelli’s concept of virtù is frequently misunderstood. Unlike Christian virtue of moral goodness, Machiavellian virtù represents practical excellence—the ability to adapt to circumstances and achieve goals effectively [52]. A prince with virtù possesses:

- Strategic flexibility: Adapting tactics based on changing situations

- Decisive leadership: Making tough decisions quickly when necessary

- Political acumen: Understanding human nature and power dynamics

- Calculated boldness: Taking calculated risks for strategic advantage

This concept directly influences modern leadership theory, particularly in crisis management and strategic planning.

The Role of Fortune (Fortuna) in Politics

Machiavelli believed roughly half of human affairs are controlled by fortune (luck/circumstances), while the other half can be influenced by virtù (skill/preparation) [53]. This balance remains relevant in:

- Business strategy: Preparing for market changes while staying agile

- Political campaigns: Having solid plans but adapting to unexpected events

- Crisis management: Combining preparation with real-time decision making

Types of principalities and how to acquire them

Machiavelli categorises principalities into hereditary and new. Hereditary principalities are easier to govern because customs and institutions are established. New principalities are harder; a new ruler must deal with resistance and build loyalty.

- Completely new principalities: These might be acquired through one’s own arms and abilities, the arms of others, fortune, or crime. Rulers who rise through their own virtù (such as Francesco Sforza, who became Duke of Milan) can hold their states more securely than those who depend on luck or powerful patrons. If fortune grants a principality without the ruler acquiring the necessary skills, he will lose it when fortune turns.

- Mixed principalities: When a state annexes a new territory similar in language and culture to itself, the prince should “live there” and allow locals to keep their laws, imposing only a small tax. If the annexed territory is different—like when the French conquered Naples—the prince should either colonise with his own people (to keep costs low and maintain control) or set up friendly local elites. Heavy taxation and garrisons breed resentment; colonisation creates loyal settlers.

- Ecclesiastical principalities: States ruled by the Church are maintained by religious institutions, so they cannot easily be controlled by secular virtù. Their stability lies outside political calculations.

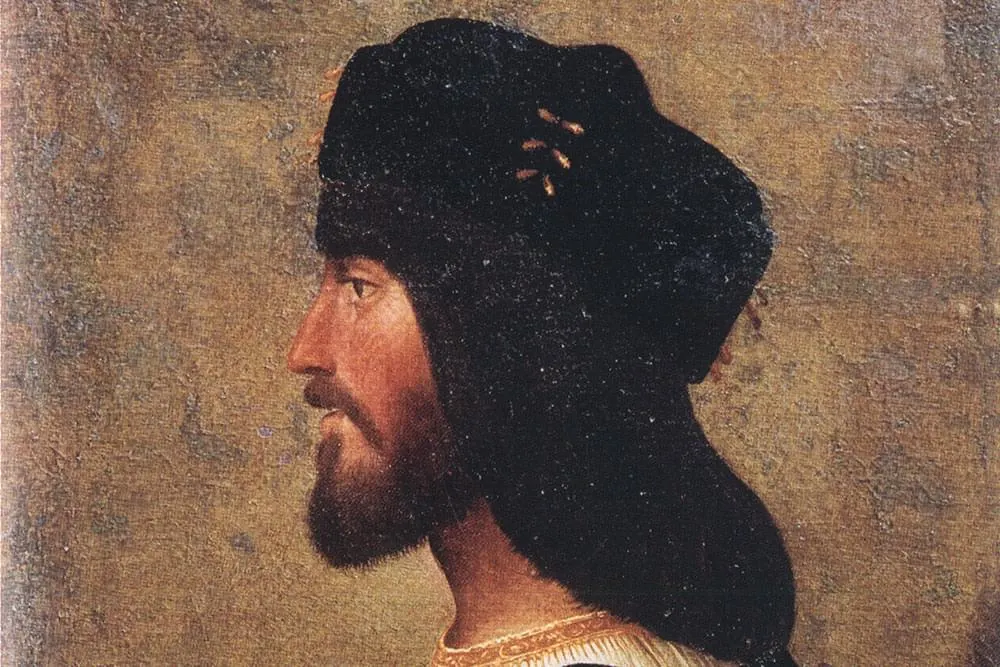

Machiavelli also warns about relying on fortune alone, as did many rulers who inherited Italian city‑states; when fortune withdrew support, their states crumbled. Instead, he praises those who combine fortune with virtù—like Cesare Borgia, who used the papal army (fortune) but also his own decisiveness (virtù) to consolidate Romagna.

The art of war and the army

No element of statecraft is more central to Machiavelli than military strength. He asserts that good laws follow from good arms. A prince must study war in peace time, read histories of great generals and exercise regularly. Relying on mercenaries is dangerous because they are motivated by profit, not loyalty. Mercenaries will flee when faced with real danger or, worse, turn on their employer. Similarly, auxiliary troops provided by allies may fight well but serve their own interest. The only reliable forces are native soldiers—citizen militias who fight for their homeland. Machiavelli’s view here reflects the Florentine tradition of civic militia and echoes the Roman Republic’s citizen army.

Maintaining power: fear, love and the people

Machiavelli’s most quoted advice is that it is better to be feared than loved if one cannot be both. He reasons that people are fickle: they may love a prince when things are going well, but fear is a more reliable motivator in difficult times. However, fear must not slip into hatred. A ruler can make people afraid by swiftly punishing disloyalty, but he must avoid seizing their property or dishonouring their families, because these actions breed lasting hatred. In Machiavelli’s formula:

- Use cruelty once and then stop. This shocks people into submission and prevents them from anticipating ongoing violence.

- Reward loyalty with leniency and stable laws. A prince should cultivate the goodwill of his subjects by encouraging commerce, agriculture and public order.

- Avoid being despised. Incompetence and indecisiveness invite contempt. The prince must appear strong and resolute.

Machiavelli also stresses that a prince should appear virtuous even when he must act viciously. People judge by appearances; displaying piety, honesty and generosity helps maintain legitimacy. The prince must be a fox to recognise traps and a lion to frighten wolves. Deception is permissible when necessary, but the prince must manage perception so that deception does not undermine trust entirely.

Advisory councils and ministers

No ruler governs alone. Machiavelli counsels princes to surround themselves with wise advisers who speak frankly. He warns that flatterers will lead a prince astray, so the prince must encourage honest counsel but make decisions himself. A clever prince sometimes appoints a harsh minister to implement unpopular measures and then removes the minister to win public approval—a tactic Cesare Borgia used in Romagna when he appointed Remirro de Orco to pacify the region and later had him executed in public, thereby distancing himself from his lieutenant’s cruelty.

Balancing generosity and parsimony

Generosity wins praise but can exhaust a prince’s resources. Machiavelli advises moderation: be liberal with spoils taken from enemies but frugal with your own revenues. Over‑generosity forces a prince to raise taxes, which engenders resentment. Strategic largesse—like rewarding soldiers after victory—builds loyalty without burdening the treasury.

Republican statecraft: lessons from the Discourses

While The Prince focuses on monarchic or one‑man rule, Machiavelli’s longer work, the Discourses on Livy, reveals his admiration for republics. Here he argues that republics can be more durable than principalities because they share power broadly and encourage civic participation.

Checks, balances and citizen virtue

Machiavelli believed that mixed government—combining monarchical, aristocratic and democratic elements—best preserves liberty. The Roman Republic endured because it balanced consuls, Senate and popular assemblies. Conflict between social classes was not harmful; rather, it produced laws that protected freedom. Machiavelli praises the Tribune of the Plebs, an office created to represent common people, because it checked patrician ambitions. To him, discord managed within institutions is a source of strength.

Civic virtue is central to republican statecraft. Citizens must value the common good above private gain, serve in the militia and accept public offices. When citizens become corrupt—seeking honours and riches over common welfare—the republic decays. Machiavelli laments that Florence fell back under Medici rule because its citizens lost the public spirit that made the republic strong. He urges measures to renew virtue: periodic renewals of laws, land redistribution to prevent oligarchy, and festivals celebrating civic identity.

The danger of corruption and inertia

One of Machiavelli’s most enduring insights is his theory of political cycles. He writes that states go through a cycle of growth, stability, decline and renewal. Success sows the seeds of decay, because prosperity breeds complacency. Without institutional checks, leaders become soft and corrupt. This applies to princes and republics alike; both must periodically return to first principles. In modern terms, Machiavelli recognises that institutional entropy erodes governments unless there is an active effort to reform.

Republican armies and militias

Like in The Prince, Machiavelli argues in the Discourses that republics should rely on citizen soldiers. He admired the Roman practice of mandatory military service and believed that citizens trained in arms were more committed to defending their freedom. He criticises Florence for hiring mercenaries, which led to military defeats and dependence on foreign commanders. His call for an armed citizenry resonates with later thinkers who linked liberty to an armed populace. In the United States, for example, the Founding Fathers drew on Machiavellian ideas when designing a republic with a militia system.

Stories from history: Machiavelli’s case studies

Machiavelli’s treatises are peppered with historical anecdotes that illustrate his points. These “war stories” make his advice concrete and memorable.

Cesare Borgia: ruthless ingenuity

One of Machiavelli’s heroes is Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI. In the early 1500s Borgia sought to carve out a state in Romagna. With papal troops and French support, he conquered the region. He then appointed a brutal lieutenant, Remirro de Orco, to pacify it. De Orco suppressed disorder through harsh punishment. Once order was restored, Borgia had him executed and displayed his corpse in the town square. This served two purposes: it satisfied the people’s desire for justice and absolved Borgia of his lieutenant’s cruelties. Machiavelli points to Borgia’s decisiveness, cunning and ability to manipulate perception as exemplary. However, he notes that Borgia ultimately failed because he relied on his father’s fortune; when the pope died, fortune abandoned him.

Francesco Sforza: virtù without fortune

Francesco Sforza began life as a mercenary captain. Through his skill and discipline he gained control of Milan and became its duke. Sforza relied on his own arms, not on mercenaries, and he built institutions that lasted. Machiavelli contrasts Sforza with those who gained power through luck—such as Ludovico Sforza, who lost Milan when fortune turned. The lesson is clear: abilities won by one’s own virtù provide durable foundations.

Agathocles and the limits of cruelty

Machiavelli recounts the story of Agathocles, a commoner from Syracuse who rose to power through brutal means. Agathocles called a meeting of the city’s senators and wealthy citizens and, once they assembled, he ordered his soldiers to kill them all. With his rivals eliminated, he seized the city and declared himself ruler. Machiavelli uses Agathocles to show that cruelty can indeed bring power, but it cannot bring glory. Agathocles lacked the moral prudence to stop being cruel after establishing his regime; he ruled through fear alone. Machiavelli admires his boldness but criticises his failure to moderate cruelty.

The King of France and the Swiss: trust in auxiliaries

When Louis XII of France invaded Italy, he relied heavily on Swiss mercenaries. At first they were formidable, but their loyalty was to their own interests. Eventually, the Swiss decided that Italy should not be controlled by a powerful neighbour and turned against Louis. Machiavelli cites this as a cautionary tale: auxiliary troops appear less threatening than mercenaries, but they can betray you when it suits them. Better to lose with your own army than to be at the mercy of another’s.

Machiavelli and morality: a controversial legacy

Misunderstood realism

Over the centuries, “Machiavellian” has become a synonym for deceitful or unethical politics. Yet Machiavelli’s own writings are more nuanced. He does not celebrate vice; he explains that rulers cannot always behave virtuously if they wish to survive. In other words, necessity may require actions that private morality condemns, but these actions are justified if they protect the public good.

Machiavelli’s separation of ethics and politics scandalised readers in Christian Europe, where political authority was often justified by divine mandate. He urged rulers to focus on worldly outcomes rather than heavenly ideals. In modern political theory, this marks a shift toward secular realism. Today leaders facing existential threats—wartime decisions, counter‑terrorism—still wrestle with the question he posed: should the safety of the many take precedence over the rights of the few?

Comparisons with other traditions: Kautilya’s Arthashastra

Machiavelli is not unique in linking statecraft to pragmatism. In ancient India, Kautilya (also known as Chanakya) wrote the Arthashastra, a treatise on government attributed to the fourth century BCE. Like Machiavelli, Kautilya advised rulers to use spies, alliances and deception to safeguard the realm. He argued that the king’s first duty is to protect his subjects and that severe measures may be necessary to maintain order. The Arthashastra details methods of diplomacy, war, law and even economic management. The parallels between Kautilya and Machiavelli demonstrate that political realism is a cross‑cultural phenomenon.

Religious and philosophical criticisms

Many contemporaries condemned Machiavelli’s advice as satanic. Church authorities placed The Prince on the Index of Forbidden Books. Moralists argued that he separated politics from Christian ethics and thereby opened the door to tyranny. Philosophers like Erasmus and Thomas More promoted idealised visions of rulers guided by moral virtue.

Later thinkers have been more sympathetic. Some argue that Machiavelli was not endorsing immorality but describing the world as it is. Others view his writings as satirical—an implicit warning to citizens about the dangers of concentrated power. Republican theorists such as James Harrington and Algernon Sidney drew on Machiavelli’s Discourses to defend mixed constitutions and civic virtue. Modern scholars still debate whether Machiavelli was a patriot, a cynic or a teacher of evil. What is clear is that his blunt realism forced subsequent political philosophy to confront uncomfortable truths about power.

Machiavelli’s influence on modern statecraft

Foundations of political science

Machiavelli can be considered one of the founders of modern political science. He approached politics empirically—collecting examples, analysing outcomes and drawing general lessons. His rejection of teleological and religious justifications in favour of observable cause and effect laid groundwork for later thinkers such as Hobbes, Spinoza and Rousseau. Hobbes’s Leviathan, for instance, echoes Machiavelli in its insistence that a strong sovereign is necessary to prevent civil war.

Realism and raison d’État

Reason of state—raison d’État—is the doctrine that the survival and flourishing of the state justify actions that might otherwise be immoral. Machiavelli’s writings prefigure this doctrine. Cardinal Richelieu in seventeenth‑century France used raison d’État to centralise power and pursue a strong state despite religious wars. In the nineteenth century, Otto von Bismarck practised Realpolitik, unifying Germany through wars and careful diplomacy. In each case, leaders followed Machiavelli’s advice: use force and cunning when necessary, manipulate alliances, and prioritise national interest.

Influence on republicanism and the United States

Although The Prince is often associated with autocracy, Machiavelli’s republican ideas influenced early modern democrats. The English Commonwealth authors and the American Founders read the Discourses and appreciated his advocacy of civic virtue and checks and balances. The Federalist Papers cite the dangers of factions and the need for institutions that channel conflict into stable outcomes—ideas reminiscent of Machiavelli’s analysis of Roman politics. The Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution reflects the belief that a militia of armed citizens safeguards liberty—a belief shared by Machiavelli.

Contemporary politics and business

Today Machiavelli’s name pops up in management seminars, corporate strategy guides and campaign handbooks. Politicians and executives quote him on leadership: “the end justifies the means” (a phrase he never wrote) or “politics has no relation to morals.” These simplified sound bites miss the nuance of his thought, but they speak to his enduring influence. In a competitive environment—whether electoral or corporate—leaders still study his insights on negotiation, crisis management and human nature. His emphasis on adaptability, control of perception and decisive action resonates in marketing campaigns, crisis communications and even personal career planning.

Machiavelli in the USA and India

Reception in the United States

American readers encountered Machiavelli in the eighteenth century alongside other classical authors. Some Puritan preachers condemned him as a teacher of wickedness, but political thinkers valued his realism. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, political scientists incorporated Machiavellian analysis into studies of lobbying, electoral strategy and bureaucratic behaviour. During the Cold War, scholars debated whether American foreign policy should be guided by idealism or realism; Machiavelli’s voice echoed in the realist camp, which advocated strategic alliances and balance‑of‑power policies.

In popular culture, Machiavelli’s name conjures images of scheming politicians. Yet his deeper impact lies in the vocabulary of political pragmatism that pervades American discourse. Words like “spin,” “power politics” and “smoke and mirrors” reflect a Machiavellian understanding of perception and control.

Reception in India

In India, Machiavelli is often compared to Kautilya. Indian intellectuals studying statecraft have noted similarities between The Prince and the Arthashastra. Both texts emphasise espionage, alliances and pragmatic rulership. Indian political leaders have been influenced indirectly by this tradition of realism. During the struggle for independence, leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak admired Machiavelli’s patriotism and willingness to challenge ecclesiastical authority. Modern Indian policymakers who pursue non‑aligned or multi‑alignment strategies on the world stage exhibit a kind of Machiavellian flexibility—balancing relations with multiple great powers to maximise national interest. In domestic politics, coalition governments often practice Machiavellian bargaining to maintain stability.

Critiques and reinterpretations

Ethical criticisms

Machiavelli’s detractors accuse him of divorcing politics from morality and encouraging tyranny. They argue that his advice undermines trust and encourages leaders to treat citizens as means rather than ends. The history of dictatorships provides ammunition for this critique: authoritarian leaders have invoked Machiavellian rationales to justify repression and war.

Defensive readings

Defenders of Machiavelli offer several counter‑arguments:

- Descriptive not prescriptive: Machiavelli describes how rulers behave, not how they should behave. He teaches the logic of power so that citizens may recognise and restrain tyrants.

- Patriotic intention: He wrote to help unify Italy and protect it from foreign domination. His harsh advice aims at a greater good.

- Call for strong institutions: His republican writings emphasise laws, civic virtue and institutional checks—hardly a manual for dictatorship.

Feminist and post‑colonial perspectives

Some modern scholars critique Machiavelli from feminist and post‑colonial viewpoints. They note that his model of virtù is aggressively masculine, valuing domination and war. They question whether his analogy of fortune as a woman to be mastered perpetuates gendered stereotypes. Post‑colonial scholars argue that his Eurocentric assumptions ignore the experiences of colonised peoples. Nonetheless, even these critiques recognise Machiavelli’s influence and engage with his ideas to develop alternative conceptions of power.

Lessons for today

Why do readers in the USA, India and beyond still pick up The Prince? Because Machiavelli captures enduring truths about politics:

- Politics is about power and perception. Leaders who ignore the mechanics of power—military, economic, symbolic—lose to those who understand them.

- People judge by appearances. A leader’s image can build or destroy legitimacy. Managing narrative and symbolism is part of governance.

- Circumstances change. Success breeds complacency; misfortune strikes unexpectedly. Leaders must adapt strategies to shifting conditions.

- Public good may conflict with private morality. Hard choices sometimes require prioritising collective security over individual interests.

- Institutions matter. Laws, checks and balances, and civic participation provide durability beyond any single leader.

These lessons are timeless. In an age of social media, cyber warfare and global crises, the tools have changed but the dynamics remain familiar. A corporate executive dealing with a PR disaster, a politician handling a scandal or a military commander facing asymmetric threats can all find parallels in Machiavelli’s pages.

Frequently Asked Questions About Machiavelli’s The Prince

What did Machiavelli actually believe about morality?

Machiavelli didn’t advocate abandoning morality entirely. Instead, he argued that political leaders sometimes face situations where traditional moral rules conflict with the greater good of the state . He believed in dual morality: private virtue for individuals and pragmatic effectiveness for rulers.

Is “the ends justify the means” really a Machiavellian principle?

While this phrase is often attributed to Machiavelli, he never actually wrote it . His actual argument was more nuanced: that state preservation sometimes requires actions that would be immoral in private life, but these should be used sparingly and only when necessary.

Why is The Prince still relevant today?

The Prince remains relevant because it addresses timeless questions about power, leadership, and human nature . Modern leaders in politics, business, and organizations continue grappling with the ethical dilemmas and strategic decisions Machiavelli analyzed 500 years ago.

Was Machiavelli really advocating tyranny?

No. Machiavelli actually preferred republican government (as shown in his Discourses on Livy) . The Prince was written as practical advice for rulers in unstable times, not as an endorsement of tyranny.

Conclusion

Niccolò Machiavelli was neither a monster nor a prophet of evil; he was a clear‑eyed observer of power. Living amid wars and betrayals, he asked how a ruler could secure the state and protect citizens in an insecure world. His answer was pragmatic: cultivate virtù to harness fortuna, build institutions, maintain a capable army, use cruelty sparingly and cultivate the people’s goodwill. He separated public necessity from private morality and, in doing so, laid the groundwork for modern political science.

In a globalised twenty‑first century, his ideas travel well between continents. Americans debate realism versus idealism in foreign policy; Indians draw parallels between The Prince and the Arthashastra. Though contexts differ, the fundamental dilemma remains: how can a leader act effectively in a world where doing the right thing and doing what works are sometimes at odds? Machiavelli does not offer easy answers, but he provides a vocabulary for thinking about the trade‑offs inherent in leadership. For that reason, The Prince and its idea of statecraft continue to rank among the most studied works of political theory in the USA, India and beyond.